BQE 2053: Building a sustainable, visionary Brooklyn-Queens Expressway

Will Harry Chapin Park be destroyed?

Is New York missing the opportunity of a lifetime to radically reimagine the crumbling, polluting and divisive Brooklyn-Queens Expressway (BQE)?

That was one cautionary take-away from the Institute for Public Architecture’s (IPA) full-day symposium, BQE 2053, at Urban Assembly New York Harbor School on Governors Island on Saturday, May 20.

Another take-away was that a visionary highway redesign could still be possible — if the city and state would jointly commit to joining the ranks of other first-class cities, like Paris, Seoul and Seattle, which have drastically redesigned their aging transportation infrastructure.

An overarching theme of the symposium was the necessity of rethinking the entire BQE corridor as a whole, rather than in segments, as part of a sustainable, multi-modal transportation network.

However, a corridor-wide redesign necessitates forming a joint city-state corridor governing body — a step that has so far not been taken as the clock continues to tick.

Currently, the city is only taking responsibility for rebuilding the dangerously deteriorated BQE Central’s Triple Cantilever section, underpinning the Brooklyn Heights Promenade. (The state holds responsibility over the BQE North and BQE South sections.)

The Adams administration discarded a 20-year plan devised by former-Mayor Bill de Blasio’s BQE Expert Panel in 2019-2020, which would have funded urgent repairs on BQE Central immediately, allowing the city roughly 20 years to devise a solution that would come closer to its corridor-wide goals. Accelerated design work and public comment sessions for a redesigned BQE Central have been proceeding over the past year.

All day symposium connects diverse groups

Despite the early-morning ferry ride and the day’s driving rain, the site of the symposium, the auditorium at the Urban Assembly New York Harbor School, was filled.

The event brought together more than 30 speakers and panelists, including elected officials, policy makers, transportation, housing experts and community groups from the north, central and south ends of the BQE.

Topics included the historic inequities of the highway that was run through some communities and not others; what a decarbonized, multi-modal network would look like; moving freight to rail and water; who gets to make the decisions; creating a “land bank” for the newly-available real estate; the importance of community engagement and “owning’ the project; and creating a consortium.

An exhibit in the island’s historic Block House brought together a variety of design proposals from the Institute for Public Architecture’s 2020 and 2022 Fellowships, ranging from the more pragmatic (truck and maritime routes), to the aspirational, such as planting forests along entire route of the roadway.

Most consequential capital project in the city today

“The replacement of the BQE is the most consequential capital project that is on the table in the city of New York today,” Councilmember Lincoln Restler said.

“It is critically important to create the time and space to talk, think and plan together right now because it is urgent, it is moving forward rapidly,” he said. “How do we move freight? How do we actually achieve our carbon goals? And how do we finally integrate this infrastructure into our communities rather than divide them?

He pointed out that 70 years ago, Robert Moses carved the BQE around influential Brooklyn Heights rather than through the middle of the neighborhood, unlike the higher-minority neighborhood of South Williamsburg, where Brooklyn Borough President Antonio Reynoso grew up.

“Right now is a moment when we need to be thinking about the future of the BQE corridor as a whole, not just focusing on the Triple Cantilever, but thinking about how does this highway interact with all of our neighborhoods, how we actually invest in a future that makes our neighborhoods healthier and that moves freight sustainably,” Restler said.

Reynoso: ‘New York state said no’

“When we talk about the BQE, we are not really talking about Robert Moses, or America’s obsession with car culture, or architectural feats like the Cantilever,” Reynoso said. “We are talking about people like me. The kids and families and residents of Brooklyn who have suffered the consequences of the BQE for generations and continue to live with them. For us, the BQE has bisected neighborhoods, [led to] high childhood asthma rates and heavy traffic. The playgrounds we grew up on, the basketball courts, covered in soot and clouded by toxic pollution.”

The Triple Cantilever is falling apart and needs to be redone, Reynoso acknowledged.

“All we are asking the state DOT to do now is to show up the way the city showed up for the [the Brooklyn Heights] portion and do the joint request with the city to the federal government, for this grant money that’s been set aside precisely for projects like this, that reconnects communities and addresses the environmental injustices of the past,” he said.

“But New York state has said no. They’ve said they don’t want to show up. They said they don’t want to be a part of it,” Reynoso said. “What concerns me, and what we should all be talking about, is that the state is resistant to even come to the table for a conversation.”

Gutman: ‘Thoughts and prayers’ for BQE North and South

Hank Gutman, former NYC DOT Commissioner and member of the Mayor’s Expert Panel on the BQE from 2019-2020, laid out a detailed analysis of how the BQE process has derailed.

“Our Expert Panel called for a corridor-wide approach to re-envisioning the BQE. So did the former Administration. To their credit, the DOT is conducting outreach in the neighborhoods they call BQE North and South, but if you look at the actual substance of what they are proposing, it is little more than ‘thoughts and prayers’ — basic improvements the DOT should be making anyway, without regard to the highway,” Gutman said.

“We’ll build a park under the highway? Nobody will want to go there. That’s thoughts and prayers,” he said.

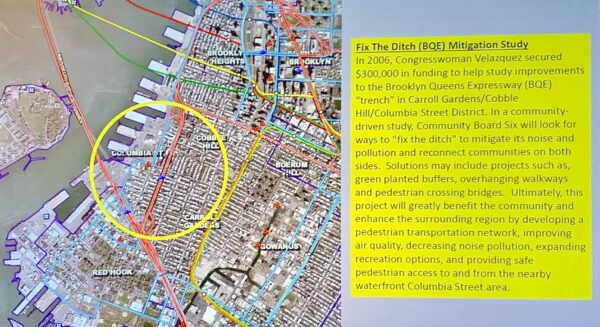

Gutman asked that at a time when all our transportation policy is focused on reducing our dependence on private cars and oversized trucks, “Why is the DOT so blindly committed to rebuilding Robert Moses’ interstate truck highway through increasingly residential neighborhoods of Brooklyn and Queens? … How in the name of equity can we possibly justify spending untold billions of dollars on BQE Central and do nothing about the ditches that divide the neighborhoods immediately to the north and south?”

The project requires the city and state to work together since some portions of the highway are under control of the state, while another is overseen by the city, Gutman said.

“Welcome to NYC. Are you new in town? Almost nothing of consequence can be accomplished in the transportation space without cooperation among multiple agencies and multiple governments,” he said.

He also brought up safety issues under the current timeline. “Even if there were a consensus plan for how to proceed today — and we aren’t even close — there is no way the DOT could get that plan approved, designed, budgeted and built before the cantilever section becomes unsafe for its current traffic.

“Salt and water cause concrete and rebar to dissolve. We all know now based on that awful building collapse in Florida … [There is still] 70 yearsworth of salt in there that mixes with new water every time it rains, even in the middle of the summer, and causes further destruction.”

DOT scrapped the waterproofing that was budgeted, which — when combined with lane reductions on the Triple Cantilever — would have bought the roadway at least another 20 years, he said.

“That plan has now been scrapped, but the clock keeps ticking.”

Gutman also described plans for the north Heights that haven’t yet sunk in for many residents.

“My favorite proposal for sheer chutzpah involves a portion of Columbia Heights which is a bridge over the highway … which the DOT is proposing to tear down and replace for hundreds of millions of dollars,” he said.

The proposal would tear down Harry Chapin Playground, as well as the direct route from the local elementary school to the park, “all in order to make the bridge a few inches taller to accommodate bigger trucks on the highway below. Yet they presented this plan to the community with no reference to the truck clearance, but instead as a plan to “improve” the parks they plan to destroy.”

DOT is also remaining mum about how its plans will impact the $450 million Brooklyn Bridge Park, Gutman said, noting that there isn’t enough space to build a bypass between the iconic Promenade and the beloved Park.

UPDATE: On Tuesday, DOT spokesperson Vincent Barone said Gutman is incorrect about a bypass necessarily encroaching on the park. “A two- or three-lane BQE Central can be built without construction or related staging intruding into Brooklyn Bridge Park’s green space. The existing space we have between the footprint of BQE and the west curbline of Furman Street is 60’ or more. So a 50’ structure can be made to fit within that without encroaching into the park,” he said.

Gutman responded to DOT’s assertion. “Let’s see the plans!” he said.

_________________

BQE 2053 speakers and panelists included:

Jeffrey Chetirko, Clare Newman, Lincoln Restler, Antonio Reynoso, Hank Gutman, Michael Kimmelman

Panel 1: Mr. Biden, Take Down this Highway!

Marc Norman; Adam Paul Susaneck; Alexander Levine & Nilka Martell; Dan Wiley; Marshall Foster

Panel 2: Community Voices – BQE 2053

Claudia Herasme, Karen Blondel, Quincy Phillip & Kiyana Slade, Noely Reyes, Cynthia McLaughlin, Daniela Castillo, Diana Reyna

Panel 3: What is a Decarbonized Sustainable Multi-Modal Transportation Network?

Tiffany-Ann Taylor, Diniece Mendes, Walter Hook, Zabe Bent, Yonah Freemark

Panel 4: Who Decides?

Elizabeth Goldstein, David McCarty, Thad Pawlowski, Monxo Lopez, Andrew Sell

Leave a Comment

Leave a Comment