Premium Content:

Alissa Wilkinson’s upcoming book explores Joan Didion’s legacy in Hollywood and American politics

The New York Times film critic talks about cultural criticism, Didion and her unexpected path to a career in media

Alissa Wilkinson is a film critic at the New York Times and recently announced her second book, “We Tell Ourselves Stories: Joan Didion and the American Dream Machine.” The book is a deep-dive into the evolution of Hollywood and its relationship to American politics through the lens of Joan Didion’s work.

Alissa Wilkinson is a film critic at the New York Times and recently announced her second book, “We Tell Ourselves Stories: Joan Didion and the American Dream Machine.” The book is a deep-dive into the evolution of Hollywood and its relationship to American politics through the lens of Joan Didion’s work.

Joan Didion is a well-covered subject, but Wilkinson’s book approaches Didion’s work with a fresh perspective. Wilkinson tackles two topics she’s extremely familiar with: cultural evolution and the figures involved in it.

Wilkinson said the book is unique from other Didion biographies because “I’m not interested in her public image as ‘Joan: the lady on the tote bag,’ so much as ‘Joan: the thinker,’ and how her eyes give us a good lens to look at a century of American history through what was happening.”

As many do, Wilkinson encountered Didion when she first moved to New York City.

“The first Didion book I ever read was ‘The Year of Magical Thinking.’ I was moving to New York right when the book won the National Book Award, and I was like, ‘Who’s this Didion lady on the subway ads?’” said Wilkinson. “My father died right after I got to New York, and it was quite sudden, and he was very young. That sense of shock that she experienced in that book was something I was extremely familiar with. The book was very moving to me.”

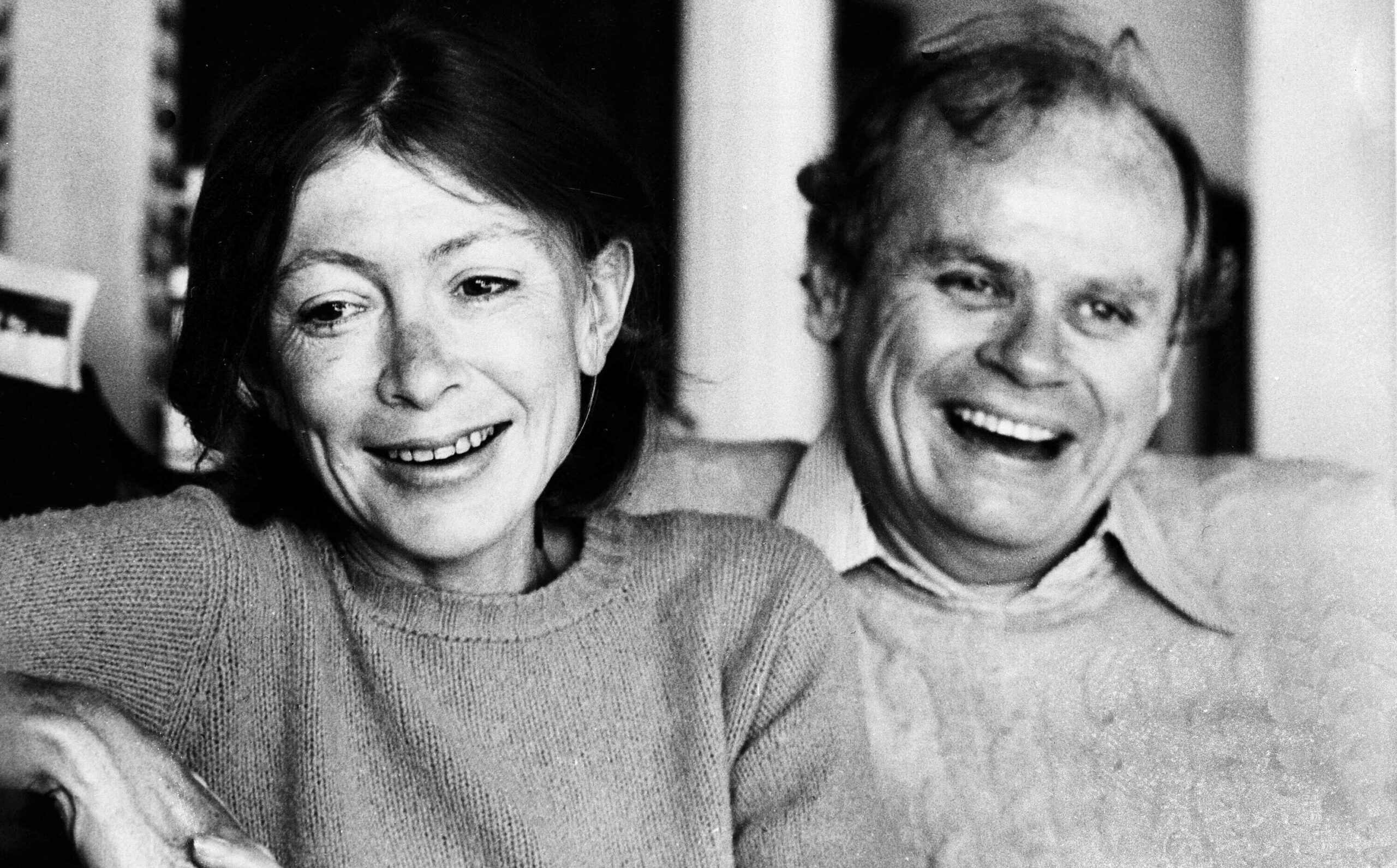

Photo: Kathy Willens/AP

After encountering Didion through “The Year of Magical Thinking,” Wilkinson delved into Didion’s larger body of work.

“I didn’t study literature in undergrad, and I wasn’t familiar with her, so I went back and read ‘Slouching Towards Bethlehem,’ ‘The White Album,’ the greatest hits; everybody reads ‘Goodbye to All That’ when they first move here, especially if they’re 21 like I was,” said Wilkinson. “I taught English, and then I got an MFA, so I certainly read some of her works. The ones I hadn’t read were the ones that I became very attached to. One was ‘Political Fictions’ — an incredible book. I remember that era of politics, even though I was a kid. That was really remarkable as a book, and then her novel ‘Democracy.’ I read it four times, and I think it might be The Great American Novel.”

In 2020, Wilkinson sought out a fresh perspective on Didion’s work that she could use for a book. As she explored Didion’s often-overlooked Hollywood era, Wilkinson began connecting the dots between Didion’s work in entertainment and her evolution as a political writer.

“I was thinking of it as ‘Joan Didion in Hollywood,’ but it expanded. The history of Hollywood is well-trodden territory, but instead, I focused on the history of Hollywood and how Americans’ fixation on-screen presence and celebrity has affected the way our politics developed over time,” said Wilkinson. “In 1980 we elected a movie star president. Now — well, you can see what has happened. That was an interesting story to tell. The more I read Didion, I realized that she was tuned into that and even wrote about it explicitly in her political writing in the 1990s. Once I realized that she was obsessed with John Wayne from a very young age, I realized there was a whole story to tell about America, Hollywood and Joan Didion from 1934 when she was born to the early 21st century.”

Didion, along with her husband John Gregory Dunne, was a prominent figure in Hollywood in the 1960s and 70s. Didion was plugged into elite social circles and worked as a screenwriter. Her movie work includes iconic films such as “Panic in Needle Park” and “Play It as It Lays.”

Wilkinson’s book delves into Didion’s buried Hollywood life and connects it to her later political work and American culture. It’s titled after a well-known but often misunderstood quote from Didion about the impulse to be entertained rather than face the truth.

Didion’s disdain for the ‘Hollywoodization’ of politics

Wilkinson’s book features an entire chapter on Didion’s little-known stint as a film critic for Vogue. Wilkinson said the reviews were telling of Didion’s political and social beliefs; Didion’s taste in movies compared to her taste in politics set a clear example of Didion’s evolution as a political writer and cultural figure.

“Because I was writing about her connection to movies, specifically, I realized that she had been a film critic in the early 1960s for Vogue magazine. When she was in New York, she shared a column with Pauline Kael, who became the legendary New Yorker film critic,” said Wilkinson. “Reading them was interesting because as a film critic, I agree with almost none of her opinions, her reviews aren’t that deep, and they’re quite short. She clearly wasn’t trying to do the kind of film criticism that I’m trying to do, but it’s very revealing of her opinions.”

AP Photo

Wilkinson discovered that Didion believed that the glitz and glamor of Hollywood should stay out of politics.

“In the Reagans, she saw people who treated politics as if it was show business, all about appearances, not about substance, and she hated it enough to switch parties over it. She registered as a Democrat because she didn’t like this, and she saw them as thinking of themselves as stage-managed,” said Wilkinson. “When you read her political writing from the 1980s onward, I wouldn’t say she ever became a liberal, but she very much opposed what she saw as the shift towards show business in politics, not only on the right.”

Didion’s political writing became increasingly cynical during the Reagan administration which led to some of her most biting and insightful work. Wilkinson described Didion’s vitriol for figures like Newt Gingrich, and how “all of Didion’s most interesting writing is about Ronald Reagan because she hated him, and she hated Nancy Reagan. The meanest thing she ever wrote was about Nancy Reagan. It bothered Nancy Reagan so much that she mentioned it in her memoir years later.”

A non-traditional path to media

Wilkinson joined the New York Times as a film critic in December 2023 and previously wrote for Vox as a senior film critic. Wilkinson will also teach at New York University’s XE: Experimental Humanities and Social Engagement program in the spring of 2025.

Before emerging in media, Wilkinson studied information technology at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute as an undergraduate and worked at an investment bank when she first moved to New York in 2005.

“When I moved to New York and started working at the investment bank, I quickly realized I had little to do during the day. They were like, ‘Why don’t you process this data?’ And it took one hour a day, and I was bored out of my head,” said Wilkinson. “I was sitting at my desk all day long, bored out of my head, and I felt like I was disappearing. I thought, ‘How hard could it be to write articles for websites?’ That was my entire thought. I Googled ‘How do you write articles for websites?’ And I learned how to pitch from that.”

Wilkinson started freelancing and blogging. She then studied humanities in graduate school and taught media and cultural studies at The King’s College for 14 years while writing criticism.

“I came at it completely wrong — I have no background in this stuff. Eventually, I was like, ‘If I can do this, I can probably do the media job, right?’” said Wilkinson. “It was a matter of falling in love with magazines more than newspapers, which I recognize is very ironic at this point. Magazines were a place to have a personality as a writer, to have expansive ideas, and not have to cover news. You saw a movie that was interesting, and then you wrote something about it, and other people who saw the movie were also interested in that.”

Now at the Times since December 2023, Wilkinson is an established voice in media and cultural criticism. Wilkinson’s experience spans teaching, writing, speaking, serving on juries at film festivals including Sundance, and more. Wilkinson noted that the Times’ investment in criticism is a beacon of hope for writers like herself.

“Something that made me happy about the Times was that A.O. Scott had this job, and he moved over to Book Review, and most publications in the world would not refill that position at this point, and would have moved to using freelancers,” said Wilkinson. “The Times values criticism enough that they’ve expanded their stable of critics over the past eight years, recognizing that not only is this something that people want to read, but it’s something worth investing in for history’s sake. Also, the Times chose to have two female critics, and that’s rare.”

The importance of criticism

Wilkinson noted that there are increasingly fewer critics as publications find less value in the dying art, but she has a few reasons why criticism should be preserved. Criticism is commonly misunderstood as critical or a summation of other people’s creativity, but Wilkinson describes it as a separate creative work.

“A big reason cultural criticism is mocked is because the word critic is so close to criticize, but they’re not the same thing. Anybody can, ‘be a critic’ by going on Letterboxd or whatever, but it’s best to think about criticism as a sub-genre of creative writing,” said Wilkinson. “I’ve often thought about it as ekphrastic writing, a very, very old genre of writing that originated with the Greeks. You couldn’t go see this vase, but I could, as a poet, describe it very closely, and then you would feel as if you had seen it but also, I’ve written a poem, so it’s two things going on there.”

Wilkinson’s approach to criticism as a type of creative writing is something she plans to teach at a writing workshop at Brooklyn’s Center for Fiction this fall, called “Expanding the World: The Review as Creative Writing.” She is also teaching a workshop based on her research on Didion’s work, “How She Wrote: Discovering Joan Didion’s Craft.”

Photo courtesy of Broadleaf Books

“You have to describe the thing you’re writing about enough that someone can get the gist of it. There is a service aspect to it, where someone who reads a review might be wanting to know if they should see the thing,” said Wilkinson. “The movie’s the coffee grounds, and I’m the coffee filter, and then hopefully the review is the nice cup of coffee you drink and enjoy, where it’s been filtered through me.”

Wilkinson said people need critics to help them sort out their feelings about media, especially movies.

“There are critics I read who I think are insane, but I love them, and I think their work is beautifully written and instructive to me because I would never see it that way,” said Wilkinson. “Then there are other people I read because I agree with them, and they help me sort out my feelings about something.”

Wilkinson said criticism is a necessary field because of its historical significance. Part of why Wilkinson is teaching the writing workshop on reviews at the Center for Fiction is because she hopes more people will learn how to write a good review for posterity.

“Being at the Times and writing the book, criticism has been important because I need to know how people responded to a movie at the time it was released because a movie is a product of its moment, but it also is the same movie 50 years later,” said Wilkinson. “I need to know what they thought in 1971, and we don’t have a record of that if critics aren’t doing their job. It matters to history.”

“We Tell Ourselves Stories: Joan Didion and the American Dream Machine” is available for pre-order and will be available in March 2025. Read more of Wilkinson’s work at the New York Times.

Leave a Comment

Related Articles

✰PREMIUM

Ritual Cabaret returns to Coney Island with call to ‘resist’

Cartoon Sketchbook: April 2