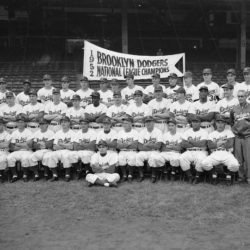

4 near misses for February

February was an odd month for Boys of Summer Birthdays. There were a bunch of them: Joe Black, Roger Craig, Don Hoak, and Erv Palica. They had several things in common. One was they didn’t last very long as Dodgers. Another? They lucked out being at the right place at the right time. A strange one.Two died young, Hoak at 41 and Palica at 54, both of heart attacks. And the one who was around the Dodgers the longest, Palica, I remember the least. Let’s have a look.

Hoak spent two years with the Dodgers of a ten-year career. He was a career .265 hitter and poked 89 homers in his career. That’s an unimpressive 8+ dingers a year. One thing he brought to the game was his personality. According to the baseball Almanac, he played ball like the throwbacks. He played like he meant it, and it meant something to him. His Latin teammates called him El Diablo Divino, the Devine Devil. Legendary Pirates broadcaster Bob Prince hung the Tiger moniker on him for the way he ferociously hunted down everything. One sportswriter even characterized him and his style of playing as vulgar.

Hoak played two seasons sharing third base with Robinson and Cox. But one of those seasons was 1955 when he played the 7th game of the World Series in its entirety, the only series game that Robinson ever missed.

Let’s throw in Roger Craig, pun intended. Craig was a lanky, 6’4” right-handed pitcher. He stood out in my mind, but not on the field. Go figure. Wikipedia tells us that he spent several years as an excellent minor leaguer and two years in the military. Craig was called up to the majors. In his debut game on July 17, Craig was the Dodgers’ starting pitcher against Cincy at Ebbets Field. He threw a complete game victory and allowed only three hits and one earned as Brooklyn walked away with a 6–2 victory. He made nine more starts for the Dodgers over the next ten weeks and was a reliever in a dozen games more; he threw two more complete games, earned two saves, and posted a very good 2.78 earned run average as the Dodgers won the National League pennant. Craig started Game 5 of the 1955 Series against the New York Yankees, worked six innings, gave up four hits and only two runs before being relieved by Clem Labine, and was credited with Brooklyn’s 5–3 victory. Two days later, on October 4, 1955, Craig’s teammate Johnny Podres shut out the Yanks in Game 7, giving Brooklyn its first and only World Series championship.

Craig was not only on the best team in baseball, he ended his career on the worst, the NY Mets, in their rookie year. It was a team so bad Casey Stengel asked, “Is there anyone here who can play this game?” Craig was well known as an original 1962 N.Y. Met. As a member of the starting rotation of the 1962 and 1963 Mets, who lost 120 and 111 games, respectively, Craig posted a nightmarish 15–46 won-lost record during his two seasons with the expansion team. “But,” Craig once recalled, “11 of those times, it took a shutout to beat me.” Despite his poor record, Craig was a stalwart of the legendarily bad team’s pitching staff. Remarkably, he threw 27 complete games in 64 starts, demonstrating that he was one of the Mets’ best pitchers. Again Stengel, who told him, “You’ve gotta be good to lose that many.”

Let me throw another at you, again pun intended, and another person who is stamped in my memory for some reason. His autograph sits on my office wall, but his stay on the field wasn’t as great as his long, fruitful post-career in league administration and management. After seeing combat in WW ll, Joe Black had a great run in the Negro leagues, coming up to the Dodgers at 28, six years after Robinson. The two were roommates on the road. Black’s career started like a house on fire. In fact, half of all the games he won (30 ), he won in his rookie season. He was named Rookie of the Year. The Dodgers promoted Black to the major leagues in 1952 at 28, five years after teammate Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier. He roomed with Robinson while on the Dodgers. Black was chosen Rookie of the Year after winning 15 games and saving 15 others for the National League champions. He had a 2.15 ERA but, with only 142 innings pitched, fell eight innings short of winning the ERA title.

Strapped for pitching, Dodgers manager Chuck Dressen brought Black out of the bullpen and started him three times in seven days in the 1952 World Series against the New York Yankees. He won the opener with a six-hitter over Allie Reynolds, 4–2, then lost the fourth game, 2–0, and the seventh, 4–2. Yet he can claim the historic act of being the first Black pitcher to win a world series game. I remember the adults saying Dressen ruined him, threw him too often, and for too long.

The spring after the 1952 World Series, Dressen urged Black to add some pitches to his strong slowball, which was his favorite pitch. By ’55, he was gone from the Bums. In six total seasons, he compiled a 30–12 record.

February produced pitchers. The last was Erv Palica, who I remember so clearly because of his very ethnic last name (Pavliecivich) and because he didn’t spell his first like my uncle Irv did. Unlike the other three, Palica seemed to be at the wrong place or with the wrong person at the wrong time. Quick a foot and with great reflexes, his manager, again Chuck Dressen, decided he should be an infielder. That experiment lasted one game where he threw six balls over the first baseman’s head. To the mound he went, but with Dressen’s dark cloud hanging over him.

Campanella said Palica had the best fastball on the team, but he mixed it up, throwing curves and an occasional knuckleball. This annoyed Dressen and was the building block of an ugly and career-ending freeze out by Dressen, his successor Burt Shotten who relegated him to the bullpen, and then again Dressen.

The 1950 season with Dressen back at the helm saw Palica having a key role in the Dodgers dash from fourth place to coming within one game of overtaking the first-place Phillies. The Dodgers lost on the last day of the season in extra innings. During one five-day stretch during that streak, Palica went 3-0, including a two-hitter. He also hit his only career home run. Get this—a grand slam!

Nineteen fifty-one, with great expectations, was a different story.

Mark Stewart, writing for SABR tells it this way, “The situation came to a head during a July game against the Pirates at Ebbets Field. Palica had been complaining about a stiff arm and a sore right hip—a painful condition that seemed to afflict his push-off leg for a week or two almost every season. This time it had “popped” while he was on the mound in the tenth inning of a July 8 game against the Phillies. Clyde King had to hustle in from the bullpen to preserve a 6–4 victory. The other Dodgers recognized that their teammate never quite felt 100 percent and ribbed him about it from time to time; still, they admired his talent and valued his self-effacing humor.

On July 18 Palica was tabbed for mop-up duty after the Pirates took a 10–2 lead. But the Dodgers came back to go ahead 12–11, at which point Palica yielded an eighth-inning home run to Ralph Kiner and a run-scoring single to Pete Reiser. The Pirates won, 13–12.” Stwart said Dressen was livid in the clubhouse.

“When asked to comment on Palica, he grabbed his throat in a choking gesture and ordered reporters to put it in print. He then launched into a tirade: “He’s got more alibis than Carter’s has liver pills! If it isn’t his fanny it’s his arm! If it’s not that, it’s his groin! If it’s not that, he’s worried about his wife! If it’s not that, he can’t run with his high blood pressure! If it’s not that, the Army is going to get him!”

“The guy is a joke around the team,” Dressen continued. “The players laugh at him. One day when he said he was ready, they gave him a big hand of applause in the clubhouse.”

When asked about Palica’s stuff, Dressen claimed he had not seen Palica throw a real fastball all season. Finally, he called Palica “a gutless kid who doesn’t belong in the majors.” Brooklyn general manager Buzzy Bavasi backed up his manager, announcing that he would cut Palica’s salary the following season—quite a proclamation considering there was still a half-season left to play.”

Palica was traded to the floundering Baltimore Orioles and retired in a few years. Stewart notes that Palica flunked his army physical because of high blood pressure. Screened at another site, he passed. Someone didn’t connect the dots. He was dead of a heart attack at age 54.

The baseball almanac gives us this statistical summary of a career that was a lot more interesting than the stats summarizing it.

| Win-loss record | 41–55 |

| Earned Run Average | 4.22 |

| Strikeouts | 423 |

| Innings Pitched | 8391⁄3 |

| Teams | |

*Brooklyn Dodgers 1945, 1947-51, 1953-54

|

|

Now they are gone, these January boys of summer. If you’re wearing a hat, give it a tip to four guys who did their best and would have done better with better managers. Happy Birthday to them all.

Leave a Comment

Leave a Comment