OPINION: Consistency needed in marijuana enforcement

If police see you smoking a joint or carrying a small bag of marijuana in Maspeth or Middle Village, Queens, you are likely to get a criminal summons or even face arrest. If police see you doing the same thing in nearby Bushwick or East Williamsburg in Brooklyn, it’s likely nothing will happen. And if by some chance you did get arrested, the district attorney’s office will decline to prosecute.

As the battle over whether or not to legalize marijuana in New York State heats up, the consequences faced by smokers in Brooklyn and Queens has grown increasingly complicated.

In Brooklyn there has been a 91 percent decrease in the prosecution of low-level marijuana offenses in the first half of 2018. The obvious question for police officers is why bother making these arrests.

Brooklyn District Attorney Eric Gonzalez argues that, “Aggressive enforcement and prosecution of personal possession and use of marijuana does not keep us safer, and the glaring racial disparities in who is and is not arrested have contributed to a sense among many in our communities that the system is unfair. This in turn contributes to a lack of trust in law enforcement, which makes us all less safe.”

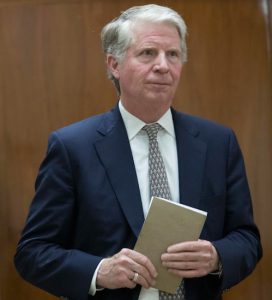

Across the invisible border in Queens, District Attorney Richard Brown says he has no plans to stop prosecuting pot smokers.

The pressure from legislators is growing on him to reconsider his stand. They argue that people of color are disproportionately singled out in pot arrests and summonses, which they wrote could hinder school and job prospects and increase the likelihood to wind up back behind bars.

“We implore you to consider the damage suffered by the men and women of color in Queens who have been unfairly persecuted under a conspicuously biased approach to policing and embrace a policy overhaul similar to the ones currently underway in Manhattan and Brooklyn,” nine Queens legislators wrote to Brown in a letter.

They claim that out that of the 17,000 low-level marijuana busts in the city last year, 86 percent of those arrested were either Black or Hispanic.

In June, Mayor Bill de Blasio and NYPD Commissioner James O’Neill announced that on Sept. 1, New Yorkers caught smoking marijuana in public would receive summonses instead of facing arrest. The policy was the result of a 30-day working group convened by O’Neill.

This is a step in the right direction even if most of the marijuana arrests ended up getting dismissed but judges who had more important concerns. But there is a part of this issue that remains unresolved.

If possession and smoking pot are decriminalized, what happens to the people who grow and distribute large quantities of the drug?

In May, DEA announced the arrest of Andrea Sanderlin, a suburban woman dubbed the “Soccer Mom,” for running a large-scale pot farm in a Queens warehouse. Federal agents discovered nearly 3,000 pot plants and state-of-the-art cultivation equipment when they raided the building. Sanderlin faces a minimum of 10 years in federal prison if she is convicted.

There is an inherent contradiction in the way the legal system is dealing with marijuana. To say the least, the government is sending out a mixed message. The state will have to decide whether or not it’s going to decriminalize marijuana including for those who possess and use and those who grow and sell pot.

Leave a Comment

Leave a Comment