✰PREMIUM

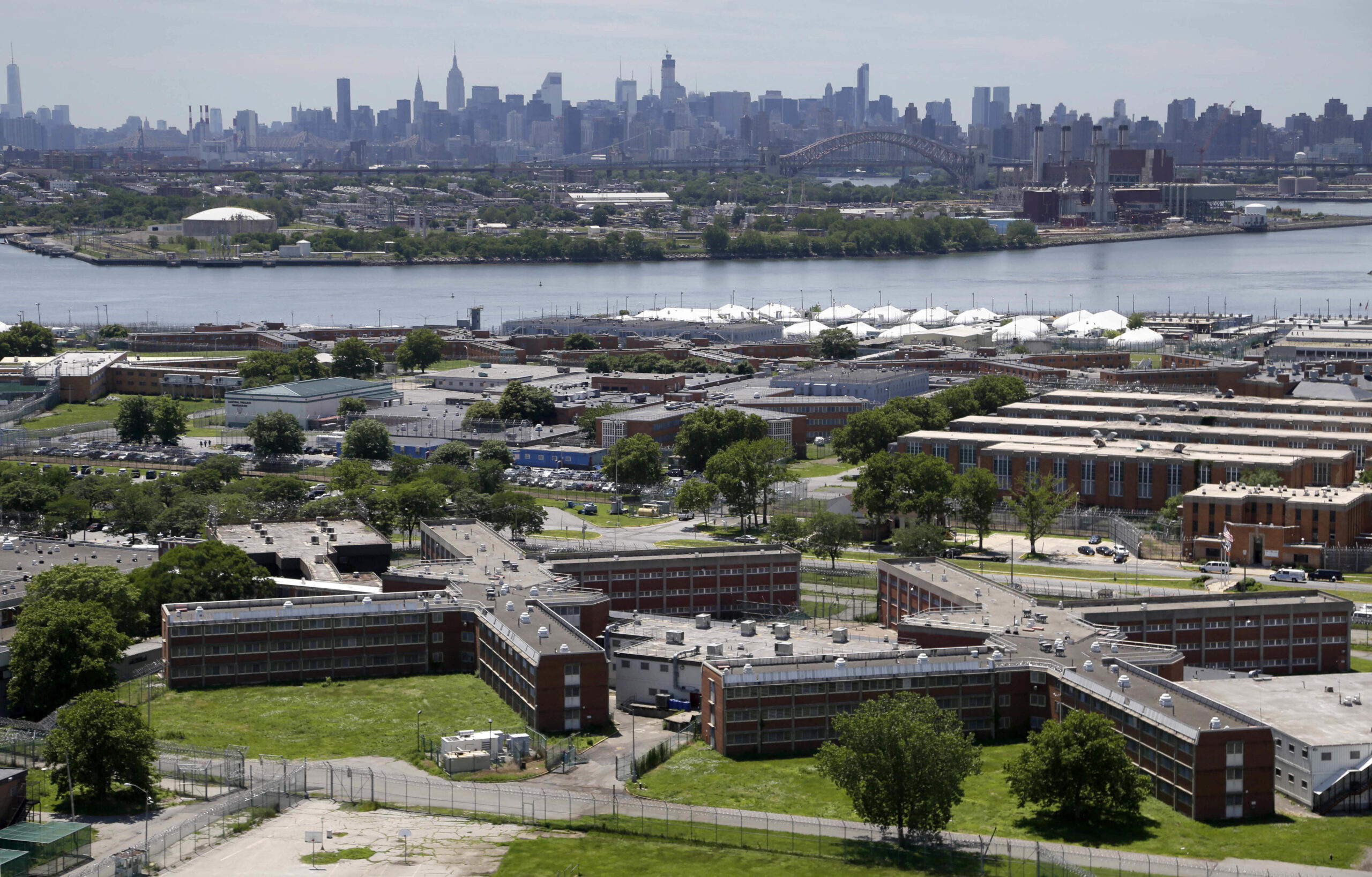

Spotlight: The strange history of Rikers Island part two: The crash

From its humble beginnings as a dumping ground for the city’s trash, through its early evolution into a penitentiary, Rikers Island was a hellscape of smoke and rot. Fires burned uninterrupted for decades, and colonies of humungous rats with a reputation for viciousness roamed free, breeding faster than any exterminator could poison, trap or hunt them.

The 1939 World’s Fair, held within sight and smell of Rikers at Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, became the inciting factor the city needed to finally confront the island’s filth. Spearheaded by Robert Moses, waste was redirected to Fresh Kills on Staten Island. Trees were planted and trash fires were covered up. In 1947, the city began phasing out open-air trash dumping altogether, replacing it with towering incinerators meant to tame the mountains of garbage that had long polluted the island’s shores.

In the postwar years, with the air a little clearer and the worst of the rat scourge contained, the city rebranded Rikers as a site of rehabilitation. Press materials touted farm work, trade instruction and a focus on reform. Inmates raised crops and livestock, learned useful skills like carpentry and labored on the grounds with the promise of shortened sentences. Officials described the island as a “self-sustaining correctional community.”

But as the island expanded and the city’s jail population swelled, a new kind of crisis took hold, one that would come to define life on Rikers until this day: the daily routine of overcrowding, neglect and brutality. Dormitories meant for 50 men held over 100. Violence erupted between inmates and was often ignored by the guards. Staff turnover was high, morale low and corruption endemic.

By the mid-20th century, Rikers Island had settled into its role as the troubled center of New York City’s penal system. But if the tedium of labor and the horror of neglect became routine, the stories out of Rikers Island never quite stuck to the script. It maintained its pre-war tradition as a stage for events so improbable they bordered on the surreal.

The crash of 1957

The trash fires of Rikers were slowly extinguished and the air was cleared of black smoke and flames, to be slowly replaced by the contrails and roaring engines of the planes taking off and landing at Laguardia Airport. Opened in 1939 as the city’s first commercial airport, Laguardia is located less than 300 feet from the eastern shore of Rikers.

From their cell windows, inmates could watch the planes taking off from the runways, close enough to make out the serial numbers stenciled on their tails.

On the evening of Feb. 1, 1957, after the airport had been operating commercially for 18 years, a Douglas DC-6A airliner with the tail number N34954 took off from Runway 4. Originally scheduled for 2:45 p.m., Northeast Airlines Flight No. 823 was delayed on the runway until 5:58 p.m. due to blizzard conditions. Approximately 60 seconds after the wheels left the tarmac, the plane was nosediving into the penitentiary grounds on Rikers.

The plane failed to gain the needed elevation and crashed into a cluster of trees, which sheared off the left wing and left engine and caused all 95 passengers and six crew members to plummet belly-first into the snow-covered fields of the prison’s historic farmyard, skidding some 1,500 feet before coming to a stop near the pig pens.

The crash could not help but arouse the attention of the island’s inmates and wardens. According to a New York Times article the next day, “The impact shook even the sturdy prison’s walls. Then the night filled with flame, reflected in the falling snow and on the drifts already tufted on the prison’s great barnyard.”

Within minutes, the wardens had released the inmates from their cells and trained their floodlights on the burning wreckage. Dozens of inmates, nowhere near adequately dressed for the fierce winter weather, ran to pull panicked and disoriented passengers from the flames and helped them to the infirmary, where they stayed to treat the survivors’ burns with oil and vaseline and wrap them in prison blankets. One inmate picked up a wriggling bundle from the snow: a baby, tossed through the jagged hole in the plane’s side amid the flames.

Despite the fears of Deputy Warden James Harrison, who had given the order to release the inmates without guards, not one inmate had tried to escape.

In large part because of the inmates’ efforts, only 20 of the passengers on the flight were killed. 25 passengers and three stewardesses suffered major injuries, and 50 passengers sustained minor injuries, while the pilot, copilot and engineer were uninjured.

“Without them, many would have died out there. They went right in there…they took [passengers] out in their arms,” a policeman on the scene told the Staten Island Advance.

“They were the people who rescued us,” Kenneth Kronen, the father of the baby picked up in the snow, said in a 2017 interview with the New York Post. “I don’t know if all of us would’ve even gotten out without them… We were all burning. It was so hot, and the plane was on fire.”

Inmate Angel Gorbea, who assisted in the rescue, recalled the experience:

“Then the explosions came. Then the whole sky, even through the snow, was lighted. We stood at the windows. We saw the people tumbling out of that ship — they were all lighted too, by the flames. We saw them and their shadows. We saw them stumble. We saw some fall, we saw some just jump out, land on their hands and knees, and then get up and run. They slipped on the snow. They beat at themselves because maybe their clothes were burning. Some just ran a few feet from the plane and rolled in the snow, as if they were trying to smother the fire on their clothes.”

The Department of Corrections later recognized the efforts of the 57 inmates who took part in the rescue operations. Of the 46 serving indefinite terms, 30 were released and 16 received a reduction of six months. Of the 11 men serving definite sentences, two received a six-month reduction from Governor Averell Harriman, and the other nine became eligible for immediate release.

The only bit of the plane to survive was the tail, the serial number N34954 still clearly visible on its side.

Come back tomorrow for part three in the Rikers saga: the Salvador Dalí art heist.

Leave a Comment

Leave a Comment