Experts weigh how NYC should protect schools against COVID this fall

One of the biggest questions on the minds of New York City’s public school families, principals, and teachers is what COVID-19 precautions will look like at schools this fall.

This school year is set to be far different from either of the last two. Hybrid learning is gone, and the city is planning to welcome every child back to their school building on Sept. 13. But even with the first day a month away and a highly transmissible COVID-19 variant sweeping through the five boroughs, city officials have not yet informed families and educators about social distancing, in-school testing, and quarantine policies.

State health officials announced Thursday that, unlike last year, they wouldn’t offer any guidance for this fall. Frustrated by the delay and eventual punting on the matter from Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s administration, state education officials have advised districts to use federal school reopening guidelines as a basis for their plans.

Chalkbeat spoke to three experts who have followed COVID-19 closely — Susan Hassig, assistant professor of epidemiology at Tulane University; Morgan Philbin, assistant professor of sociomedical sciences at Columbia University; and Cynthia Leifer, professor of immunology at Cornell University — about the best ways to protect children and educators at school based on what is known so far about the delta variant.

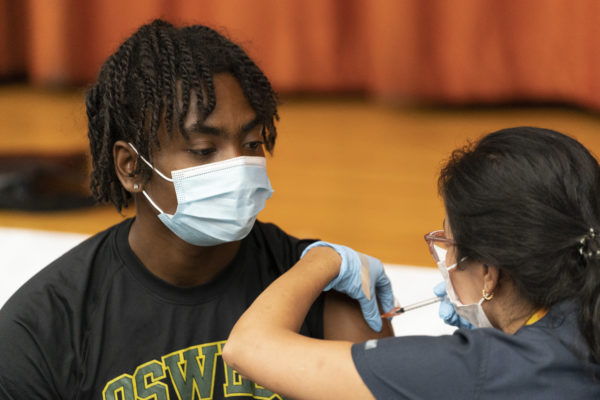

They agreed that getting vaccinated is the best possible protection against COVID-19, since vaccinated people are shown to be far less likely to become infected and rarely develop severe illness or die. The city saw an average 127 new cases per 100,000 people over the past week, which poses “high” risk of transmission within schools, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But with the Delta variant in the mix, vaccinated people who do get COVID-19 can still spread it – though potentially for just a short amount of time — which can be problematic for children 11 years old and younger who are not yet eligible for a shot. That means schools should use layers of protection to stymie virus spread, these experts said.

About 60 percent of city teachers have been vaccinated, but that figure is likely higher since many teachers may have been jabbed outside of New York City, officials said. Teachers will also be required to get vaccinated before the start of school or get tested weekly. As of this week, about 43 percent of New York City children ages 12-17 have received at least one dose. City officials are hoping to boost those numbers through a vaccination campaign this month.

The experts said there is not yet good evidence about how the delta variant affects unvaccinated children, but all three said infected children are still usually showing mild symptoms. Hospitals in several states have reported seeing more COVID-related pediatric hospitalizations. As of late July, the CDC reported that children ages 5-17 were just as likely to get infected as other age groups but were among the least likely to be hospitalized or die.

AP photo by Mark Lennihan

After vaccines, the most important protection is universal masking, experts said, which Mayor Bill de Blasio has already committed to. Social distancing and good ventilation come next. The education department is promising two air purifiers for every classroom and has been working to fix faulty ventilation systems.

But all of these protections — also recommended by the CDC — must be coupled with quarantining and closure policies, these experts believe. While infection rates remained very low in New York City schools last year, just about 40% of children attended in person by the end of the school year.

Social distancing

Last academic year, schools were required to maintain six feet of distance between students for most of the year. That was reduced in the spring to three feet for younger grades after the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention loosened some of its guidelines.

This year, New York City schools can implement three feet of distance in their buildings if possible, but it won’t be required, according to guidance shared with administrators on Thursday from the city principals union. That’s in line with CDC recommendations that call for such distancing but not at the expense of fully reopening buildings.

Hassig, Philbin, and Leifer said distancing is still an important factor in limiting virus spread, but less key than keeping masks on and boosting vaccination rates. If schools cannot keep students apart because of space constraints, Hassig suggested they limit gathering in areas where masks come off, such as a cafeteria. She suggested, if possible, having children grab food and eat in classrooms, or have children alternate days that they eat in the cafeteria.

Hassig thinks cloth masks will offer enough protection, but they should be tightly fitted and worn over the nose at all times. Teachers and classroom aides should make sure students are wearing masks correctly, she said.

Leifer emphasized that there’s a careful balance between implementing every possible anti-virus recommendation and keeping children out of school.

“We need students back in person, and if they can’t be three feet or six feet apart, if we have these other protections in place, they’re going to be reasonably safe,” Leifer said.

Closures

Classroom and building closures were highly debated last year, when just two unrelated virus cases caused whole schools to shut down. That policy, which public health experts called overly conservative, resulted in frequent two-week closures that disrupted stability for children, working caregivers and teachers. City officials later changed their policy to close buildings only when there are positive cases in four separate classrooms.

During summer programs, vaccinated people without symptoms did not have to quarantine if a classroom or the building closed. Just .2% of in-school tests have come back positive over the course of the summer. But as of Friday, 247 classrooms were closed, with no buildings currently closed.

All three experts agreed that classrooms and buildings should close if there are positive cases since many children will not have been vaccinated, and while children may be less likely to get sick, they could take it home to more vulnerable family members. Without any such rules, virus spread could “go unchecked,” particularly because so many children can’t get vaccinated, Leifer said. But they also agreed that there is no “magic” policy that will perfectly limit spread.

“If rates are incredibly low in one neighborhood and incredibly high in another, coupled with vaccination rates, the risk is so much different,” Philbin said. “Our goal is to catch every person as early as possible so that they don’t transmit further, particularly among an unvaccinated population.”

Philbin believes the city should consider tailoring building closure rules for schools based on their vaccination rates, coupled with the surrounding neighborhood’s vaccination and infection rates.

Testing

Last school year, officials initially required monthly testing of 20% of students and staff then bumped it to a weekly routine in December 2020 after schools were closed amid a rise in COVID cases.

For summer programs, 10 percent of students and staff at each site are tested every other week, with a larger portion tested when positive COVID cases pop up. Just 69 tests of more than 36,000 so far came back positive, city data show. But in areas like New York City where transmission is considered moderate or higher, the CDC recommends offering testing at least weekly to unvaccinated students and staff.

All three experts believe there should be some level of in-school testing because that will be key to catching and isolating positive cases, including among asymptomatic people who can still spread the virus.

Hassig believes the city should start with weekly random testing of 20 percent of students and staff. That could be a huge logistical and financial burden given New York City’s size, but it will be key for “trying to keep a handle” on virus spread, Hassig said.

She also believes that if a classroom closes due to a positive case, there should be additional testing of people in the surrounding rooms because those people “are more likely to have mingled.

“If you’re finding a lot of cases at 20 percent, it would suggest there are probably more,” she said.

Leave a Comment

Leave a Comment