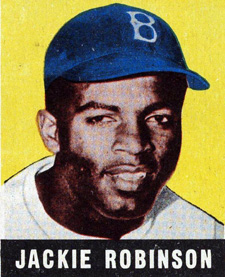

Met Displays Baseball Cards of Players Who Broke the Color Barrier

1.%20Jackie%20Robinson%2C%20Leaf%20Gum%20Co.%2C%20%20Baseball%27s%20Greatest%20Stars%201948-49.jpg

In Honor of Jackie Robinson’s Debut with Dodgers 65 Years Ago

On Sunday, Major League Baseball gave us a chance to remember that this beloved sport can be much more than a game.

It was Jackie Robinson Day — April 15 — the 65th anniversary of Robinson taking the field for the Brooklyn Dodgers, thus breaking the color barrier and changing baseball — and the country — forever.