Preserving his Bensonhurst family legacy, writer Daniel Paterna heightens awareness of all family legacies

Multi-generational immersion in food

leads an Italian-American back to his roots

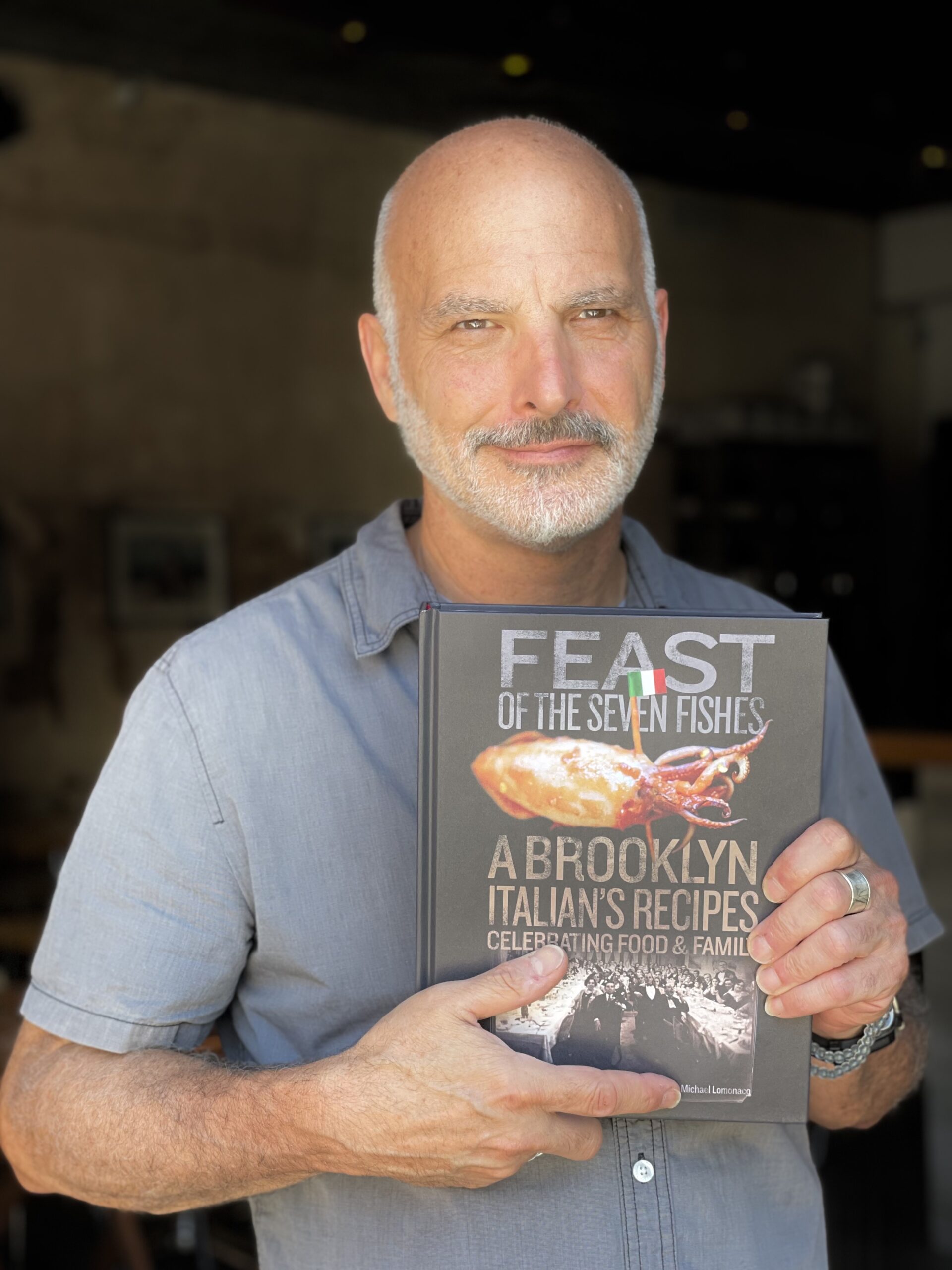

Daniel Paterna is a Bensonhurst native whose Italian-American heritage and eye for design melded into his best-selling book, “Feast of the Seven Fishes,” named for the famous Christmas Eve meal. As much a memoir as a cookbook, Daniel’s story spans multiple generations, with tales of immigration, love, and, at the forefront, good, simple food that fosters family and community. In speaking with Daniel, it’s obvious that his dedication to keeping his family heritage alive is as strong as his dedication to his own children.

Daniel Paterna is a Bensonhurst native whose Italian-American heritage and eye for design melded into his best-selling book, “Feast of the Seven Fishes,” named for the famous Christmas Eve meal. As much a memoir as a cookbook, Daniel’s story spans multiple generations, with tales of immigration, love, and, at the forefront, good, simple food that fosters family and community. In speaking with Daniel, it’s obvious that his dedication to keeping his family heritage alive is as strong as his dedication to his own children.

Tell me about yourself and your work.

I was born in 1958. I grew up in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. I grew up in my grandfather’s house that he had built. He saved his money from being a tailor his whole adult life. We still live in the house part-time. I went to Catholic grammar school. I graduated from New Utrecht High School, famously known as the setting of the television show “Welcome Back Kotter.” I went to New York City Tech for advertising and design. Eventually, I found my way through Pratt Institute for a degree in art and design.

“Food is like commerce. It’s like part of your heart. It’s an honorable way of life.”

As an Italian-American, some dishes have been changed, and overdone, and oversauced. I strive to keep it as pure as possible. A dish like beans and escarole, which will be in my next book, is literally just beans and escarole. I kept self-diminishing and asking why people would want such simple dishes. But simple dishes are like the way we learned to tie our shoes. It’s what we grew up with. They are nearly forgotten, and my purpose was to reanimate the idea of why these dishes were so ubiquitous, their nutritional value and why we never got tired of them.

How was I going to portray them in a way that wasn’t snooty or terribly pedestrian? Stuffed calamari, for example, was a special dish back in the day. It was like making a steak or lobster dinner for someone. When I moved to Boston, I called my mom and said, “There’s a restaurant called The Daily Catch with stuffed calamari. You must come here because they’re exactly like you make them, with raisins, pignoli, cheese, breadcrumbs, and egg.” She came, and I nervously brought her, and she agreed with me.

Over the years, they slowly phased them out. I asked one of the owners why stuffed calamari left the menu. He said it was because people don’t want it anymore. There are too many things in it.

Before my grandmother passed away, she had this doctor that she had total faith in. In the pouring rain, we brought him a pot full of thirty stuffed calamari because she wanted to thank him for diagnosing something she had. That was, to her, like bringing him a pot of gold. Food is like commerce. It’s like part of your heart. It’s an honorable way of life. Over the years, the Daily Catch has brought back stuffed calamari, and there it is on the book’s cover. I put it there because I wanted it to say, “Hello, remember me?” It’s the redemption of stuffed calamari.

It deserves its moment in the spotlight! I also want to know about these food vendors you feature in the book. Is there one that sticks out to you in particular?

The vendor that sticks out to me is one of the only ones that no longer exists: the fish market. This isn’t to detract from the other vendors. I spent hours in line at that store waiting to buy fish two days before Christmas Eve. Standing in a line at least a block long with other Italian-Americans — either first-generation, second, or third, or fourth — everyone was sharing stories about how their grandparents made dishes. The guy who ran it, Angelo, was a very animated character. He would be directing deliveries in and out of the building, and it was like performance art. You’d walk out of there with five pounds of fish, ready to prepare it for your relatives. That’s always been a standout.

I remember when they closed. I made a little video of people just walking up to the corrugated steel gate that was drawn up over the beautiful displays of fish that didn’t exist anymore. People were practically making the sign of the cross because it was that meaningful.

Just like the closing of the fish market or your favorite Chinese-American institution or Jewish-American institution, it’s not going to be there forever. How do we transition over the memories of the culinary history we hold so dear? That’s why I wrote the book.

There are innumerable places like this in New York, lost to history unless someone memorializes them. It’s very important work. Speaking of work, you mentioned another book you have coming out. Can you tell me about that?

During the production of my first book, my daughter had just started high school and was unfortunately struck by an anxiety eating disorder. Recovery took a long time because she wanted to recover at home, and there’s a specific method of doing that. I was the chief cook, bottle washer and primary caregiver. I was it. Over the years, she transitioned from an omnivore to vegetarian to now vegan. I did Italian vegan food as much as I could. I basically threw caution to the wind and said, “Forget the nutritionist. I grew up with nutrition.” Over the years, she wouldn’t eat some of the dishes as she transitioned to vegan, like meat sauce or the Feast of the Seven Fishes.

She would always help me cook. On Christmas Day, we’d wake up and make lasagna, whether it had meat or not. I’d make a meatless version for her, and she went through the ritual with me. She said one thing that threw me over the edge. She said, one day, “Dad, even though I didn’t eat everything that you made, the fact that you made it so consistently and traditionally was something that grounded me and got me through my emotional stress.” That was the inspiration for the next book.

I’m writing a book about relying on my Italian culinary heritage in the effort to help my daughter recover from anorexia. It’s about how I survived. My daughter would write a parallel story to mine. We had two different states of mind. Mine was a parent; hers was a patient and daughter. Everything I’ve ever read about eating disorders is clinical: “It looks like a duck, smells like a duck; it’s a duck.” There’s no field guide, per se. Not to say this is a field guide, but at least it’s a story about a regular person taking care of their extraordinary, wonderful daughter, who is in such pain, and how we all survived. There’s no magic to it. It’s just consistency and love. It’s really not about food. It’s not really something that people talk about.

One of the vendors in my book, Coluccio’s, is a well-known Italian importer on 60th Street in Bensonhurst. When my book came out, one of the owners asked me, “I’ve been writing a book for years. I love yours. If I ever get my book published, would you work on it with me?” Her book is coming out in the Fall. It’s called “The Italian Daughter’s Cookbook.” I photographed and designed it. It’s like the sister of “Feast of the Seven Fishes,” and it’s being published by my publisher, PowerHouse Books. I introduced them, and to my pleasant surprise, they took a chance on her cookbook (which isn’t the type of project they usually do) based on the success of my book. I’ll have two books under my belt, and, who knows, it could be my fourth career.

Leave a Comment

Related Articles

Peppino Joe Brings the real ‘Average Joe’ Brooklyn Italian American experience to social media

Premium Content

Experience and celebrate Brooklyn’s ‘Woodstock of Eating’

Emma’s Torch graduates its 50th cohort of refugees-turned-restaurant workers

Leave a Comment

Bensonhurst

View MoreThe Brooklyn Daily Eagle and brooklyneagle.com cover Brooklyn 24/7 online and five days a week in print with the motto, “All Brooklyn All the Time.” With a history dating back to 1841, the Eagle is New York City’s only daily devoted exclusively to Brooklyn.

© 2024 Everything Brooklyn Media

https://brooklyneagle.com/articles/2024/04/26/preserving-daniel-paternas-bensonhurst-family-legacy/