On This Day in History, February 25: Sanitary Fair Raises Big Money for Civil War Soldiers

In 1864, the Brooklyn Academy of Music on Montague Street hosted the Brooklyn and Long Island Sanitary Fair, a fundraiser for the Sanitary Commission, which provided medical assistance to Union soldiers on the front lines of the Civil War. The fair, largely organized by women’s church committees, began on Feb. 22, 1864, and ended a few weeks later on March 8.

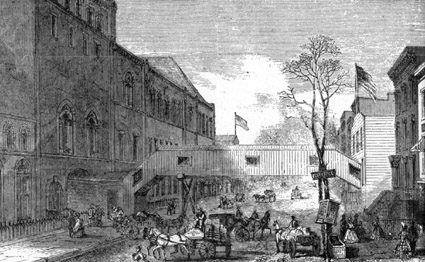

Two temporary buildings were erected on Montague Street to augment the academy in accomodating the fair, and the Taylor Mansion, at Montague and Clinton streets, was converted into an art gallery.

It was a tremendous success, raising $402,943.74 (millions of dollars in todays terms), and a great point of pride for Brooklyn, which had been invited to join New York’s sanitary fair, but in going it alone, outshined the metropolis across the river.