Carl Erskine: A boy of summer

Often I have quoted the adage, “Only the good die young.” This was not the case when it came to Carl Daniel Erskine, dead recently at 97. Any follower of the Sunshine Boys knows all about Erskine the pitcher, that overhand delivery, that over-the-shoulder look back at the plate by the batter when he was either struck out or uncurled himself from the missed swing at “Oisk’s” right curveball that he threw from over the top. It came at you eyes high and ended up at your ankles. But the beauty of Carl Erskine was also his inner beauty.

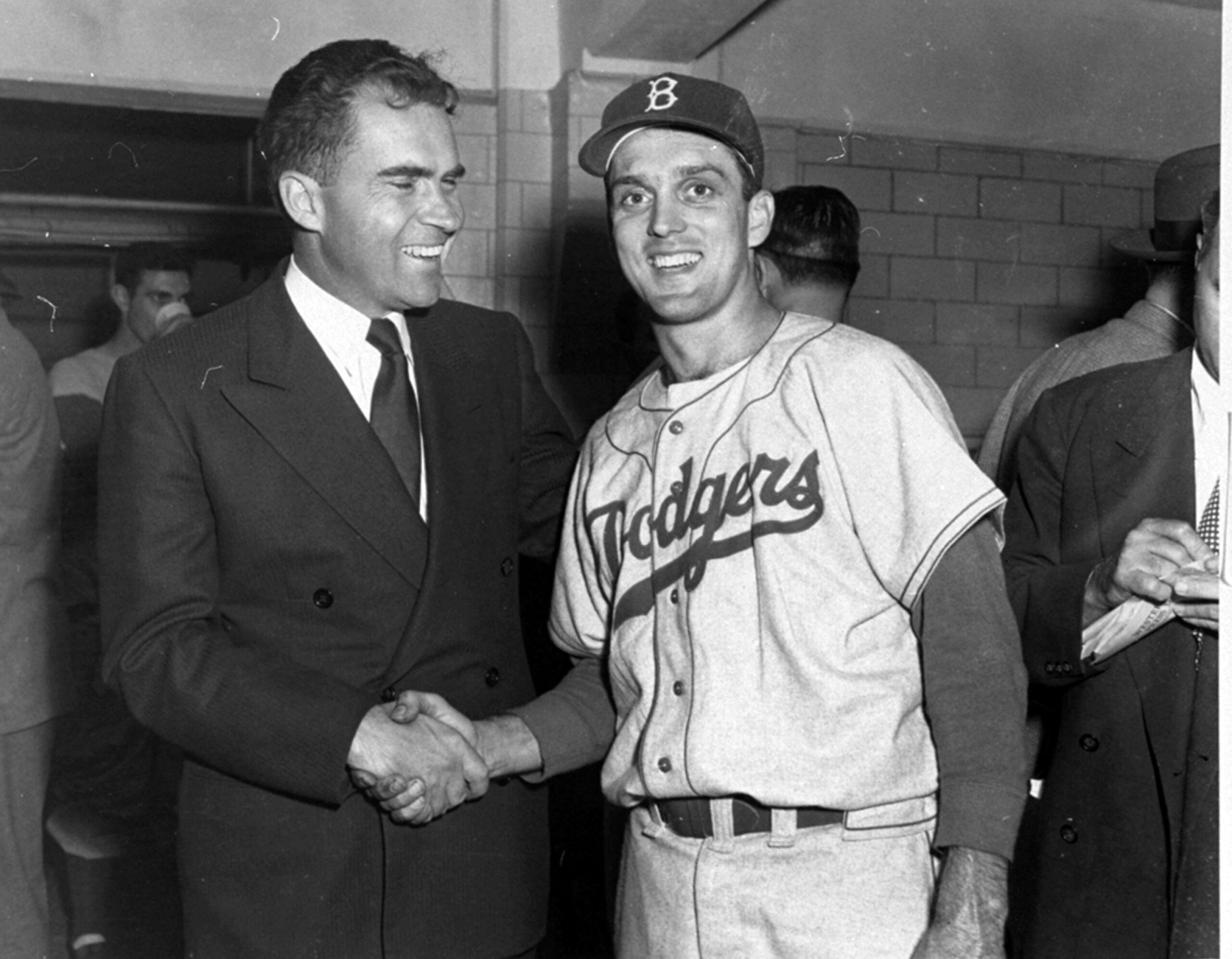

Erskine was not a fireball presence in the clubhouse, yelling, whooping, and hollering to get everyone up. He was the calming, soothing presence that helped everyone keep their jerseys on, so to speak when things were tight. He was the father’s presence. His teammates loved him. Not a bad word could be found about him. And believe me, this writer tried. He complimented his fielders for good plays but had nothing but encouragement for the guy who screwed up a play. The NY Daily News, not known for flattery, said that Erskine “was one the classiest men to ever play the game.”

He married Betty Khory who was born in 1924. She passed in 2015 having spent 77 years as Mrs. Erskine. The Herald Bulletin called her “his ultimate teammate.” They had four children. One was a boy Jimmy. It is in this story we see the true man. Jimmy was born with Down Syndrome. Not only would he not be a ballplayer, but it appeared that he wouldn’t be much other than a sweet, kind, loving child. It was to that child that Erskine devoted his life. Early on he set up a trust fund so there would be care for life if God forbid something happened to him. The Indy Star said, “In the 1960s, children with intellectual disabilities weren’t usually taken out in public. They typically didn’t receive an education and, if they were at home instead of in an institution, they were kept hidden away.”

Brooklyn Boro

View MoreNew York City’s most populous borough, Brooklyn, is home to nearly 2.6 million residents. If Brooklyn were an independent city it would be the fourth largest city in the United States. While Brooklyn has become the epitome of ‘cool and hip’ in recent years, for those that were born here, raised families here and improved communities over the years, Brooklyn has never been ‘uncool’.