Danny Kaye: A Brooklyn dynamo remembered

Throughout generations, Brooklyn has seen numerous budding talents take root and sprout into theatrical legends. None had germination as perfectly metaphoric as that of six-year-old David Daniel Kaminsky, who made his stage debut as a watermelon seed in a pageant at P.S.149 at 700 Sutter Avenue. Having forgotten to cover his ears, which protruded under a mess of red hair, the greasepainted tot, who would endear himself to the world as Danny Kaye, attracted the first of countless laughs, thus propelling a comic dynamo toward his multi-media career.

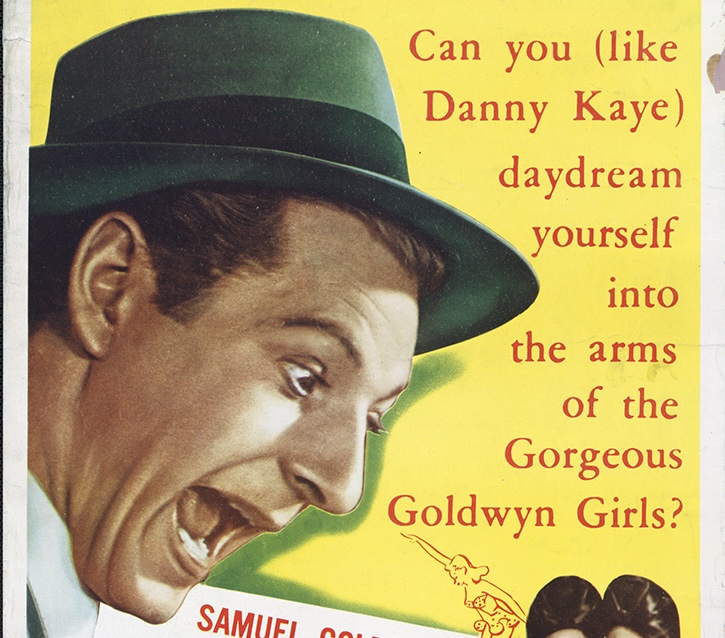

Every year during the holiday season, millions of people are reminded of Danny’s spectacular comedic, vocal and dancing talents while viewing the holiday classic “White Christmas,” in which he teamed with Bing Crosby, Vera-Ellen, and Rosemary Clooney to perform old and new Irving Berlin compositions. This perennial favorite is one among many enormously popular Kaye films that displayed his brilliance throughout a long movie career, such as gems like “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty,” “The Inspector General,” “Hans Christian Andersen,” “Knock on Wood,” “The Court Jester” and “Merry Andrew.”

Those who wish to further explore all facets of Danny’s illustrious legacy should visit the “Danny Kaye and Sylvia Fine Collection” at the Library of Congress (LOC), where manuscripts, scores, scripts, photographs, sound recordings and video clips are available online, courtesy of Danny’s wife Sylvia and their daughter, Dena Kaye. This archive serves as a major source for this chronicle of Danny’s history in the borough.

Leave a Comment

Related Articles

Premium Content

Brooklyn Waterfront Artists Coalition launches spring season in Red Hook

Premium Content

South Brooklyn ballet company hosts its second annual “Cocktail Caper”

Premium Content

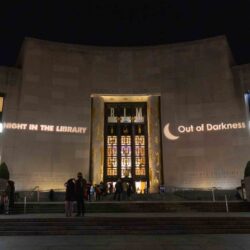

Brooklyn Public Library hosted more than 4,000 guests for Night in the Library

Leave a Comment

East New York

View MoreThe Brooklyn Daily Eagle and brooklyneagle.com cover Brooklyn 24/7 online and five days a week in print with the motto, “All Brooklyn All the Time.” With a history dating back to 1841, the Eagle is New York City’s only daily devoted exclusively to Brooklyn.

© 2024 Everything Brooklyn Media

https://brooklyneagle.com/articles/2024/02/21/danny-kaye-a-brooklyn-dynamo-remembered/