Keeping our city and our minds resilient: ‘Climate Futurism’ at Pioneer Works

Photos: John McCarten/Brooklyn Eagle

Full slideshow below

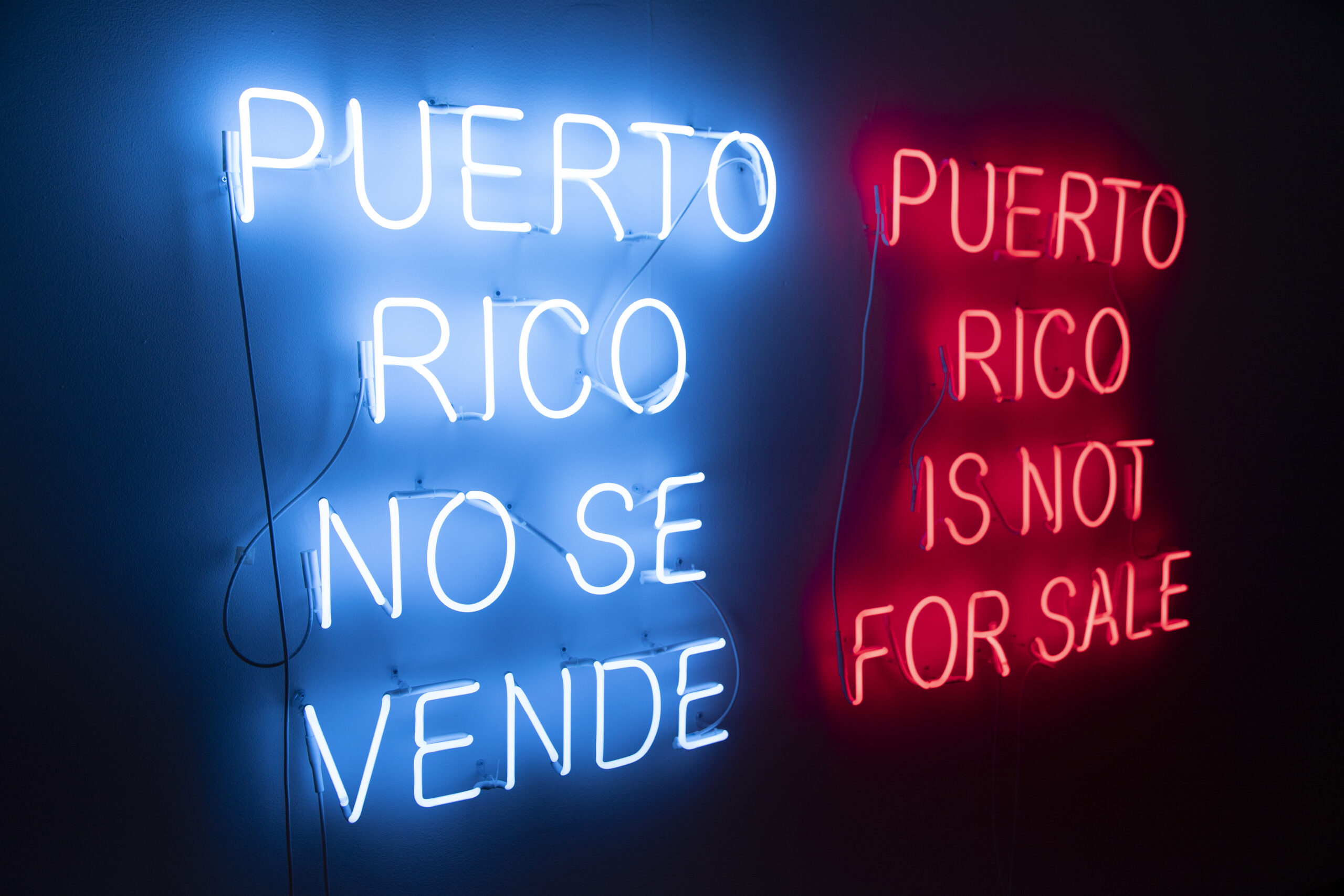

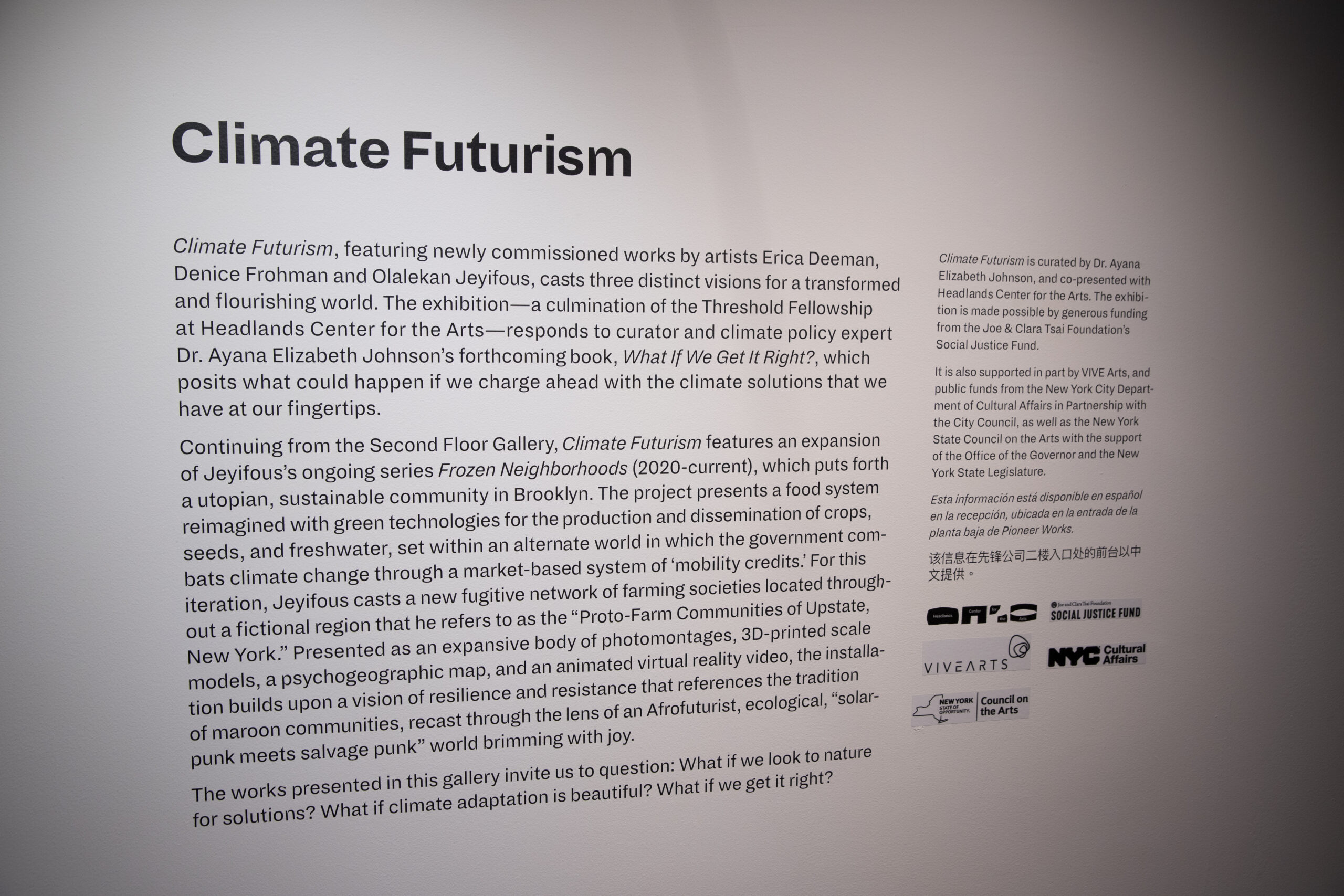

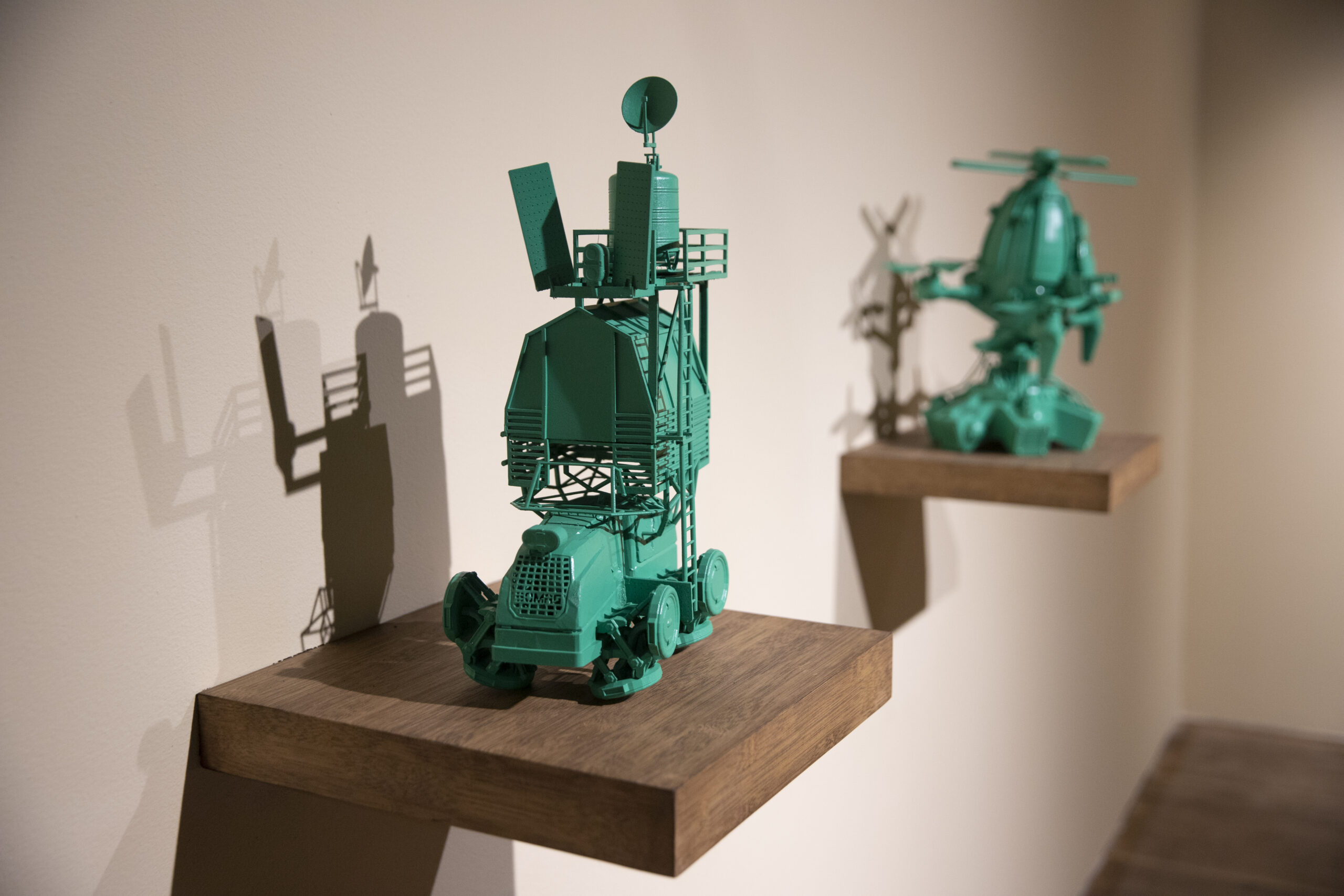

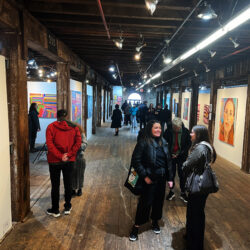

RED HOOK — Pioneer Works, a coalition of scientists and artists organizing seminars, exhibitions and performances in an effort to cultivate an interdisciplinary community, hosted “Climate Futurism,” an exhibit from Oct. 6 to Dec. 10, with a corresponding panel.

RED HOOK — Pioneer Works, a coalition of scientists and artists organizing seminars, exhibitions and performances in an effort to cultivate an interdisciplinary community, hosted “Climate Futurism,” an exhibit from Oct. 6 to Dec. 10, with a corresponding panel.

It’s not difficult to find bad news about the climate. Recently, researchers reported that 2023 will be Earth’s hottest recorded year, 1.43º above pre-industrial levels; this comes after the hottest decade on record. As a result of this unprecedented warming, a/c use is expected to rise, further increasing energy use; ocean temperatures rose to over 101º in Florida this summer. Meanwhile, this year, emissions have continued to climb; scientists recently discovered the heating effects of CO2 compound the more of it is present, implying previous projections could be too forgiving; furthermore, another 2023 study found harmful aerosols emitted from cargo ships were actually cooling the Earth by forming clouds that blocked sun rays, that is, until regulations required them to use cleaner fuel.

Each year, governments’ inaction on dramatically limiting greenhouse gas pollution results in increasingly dire forecasts, and it has been known for some time now that raising the Earth’s global temperature above 1.5º pre-industrial levels could result in a global warming feedback loop. The future seems bleaker and bleaker. But “Climate Futurism” imagines a world where humans continue to thrive.

Full slideshow below

Leave a Comment

Related Articles

Premium Content

Brooklyn Waterfront Artists Coalition launches spring season in Red Hook

Premium Content

South Brooklyn ballet company hosts its second annual “Cocktail Caper”

Premium Content

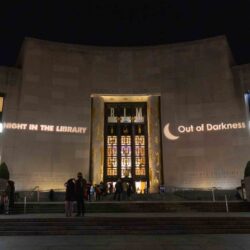

Brooklyn Public Library hosted more than 4,000 guests for Night in the Library

Leave a Comment

Northern Brooklyn

View MoreThe Brooklyn Daily Eagle and brooklyneagle.com cover Brooklyn 24/7 online and five days a week in print with the motto, “All Brooklyn All the Time.” With a history dating back to 1841, the Eagle is New York City’s only daily devoted exclusively to Brooklyn.

© 2024 Everything Brooklyn Media

https://brooklyneagle.com/articles/2024/01/08/climate-futurism-at-pioneer-works/