Conference on climate hosted by Brooklyn Botanic Garden, The Nature Conservancy and the Climate Museum

Photos: John McCarten

WASHINGTON AVENUE — Entering the Evolution of Trees exhibit at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, the first thing you detect is the increase in humidity hitting you in the chest. The room, though not muggy, appears to be temperature-controlled. Shortly after, you notice the purity of the air. It’s impossible to detect any hint of smog or a bog-like effluvia of rotting plants. The plants in the exhibit are arranged chronologically in the order in which they appeared on Earth.

WASHINGTON AVENUE — Entering the Evolution of Trees exhibit at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, the first thing you detect is the increase in humidity hitting you in the chest. The room, though not muggy, appears to be temperature-controlled. Shortly after, you notice the purity of the air. It’s impossible to detect any hint of smog or a bog-like effluvia of rotting plants. The plants in the exhibit are arranged chronologically in the order in which they appeared on Earth.

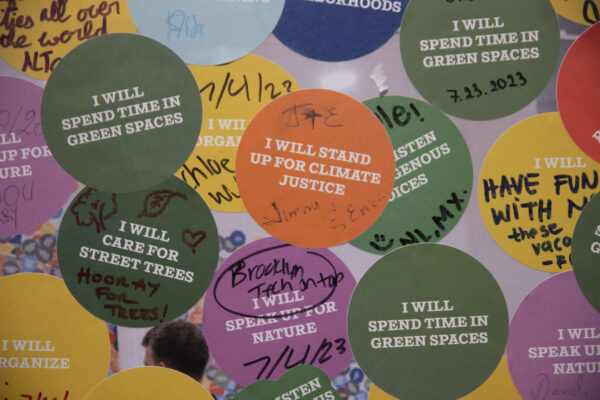

On Thursday, Sept. 21, the New Climate Reality, a panel discussion, pulled its attendees through and below the exhibit where two installations awaited. One was from the Climate Museum: an extension of its sticker wall where visitors pledge to improve the environment through small and attainable actions. The other, Witness Trees, from artist Carolyn Monastra, consisted of photographs of trees in distressing situations, some printed over the glass windows. Brooklynites filed into the room as the panelists drank water and talked.

Adrian Benepe, President & CEO of the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, gave a short preamble before the discussion began. The subject was a union of data, nature, and tradition, or as Benepe said, “climate, trees, and art.” Benepe tried to stay hopeful but admitted, “We are facing a crisis. I don’t know what we can do to convince the disbelievers,” before letting the panel take over.

Maxwell responded with an anecdote about an event at City Hall Park focused on a law requiring officials to include trees and canopy in long-term sustainability planning through the NYC charter. Protesters showed up with handmade messages and headpieces. Maxwell co-leads Forest for All NYC, a coalition guided by the “NYC Urban Forest Agenda.” During the coalition’s launch, each participant wrote a haiku. They strive to enrich the canopy coverage throughout the city created by its trees, which they call NYC’s Urban Forest. Currently, the city has 22% coverage. Significant cooling benefits would begin to occur at 32%.

The council recently passed a bill mandating trees and canopies inclusion into PlaNYC, which compels the current administration to update its sustainability plan every four years regardless of who or what party is in office. The coalition is pushing another bill, Introduction 1065, to create a master plan for managing trees across all property types and report on tree distribution to support environmental justice. “In many low-income communities and communities of color in New York City, and really across the country, we see an institutionalized racism where redlined communities just don’t have trees, don’t have enough parks, don’t have urban canopy coverage, and what that means is these communities are hotter, they’re dealing with urban heat island effect, they’re dealing with poorer air quality…” said Hernandez.

Redlining refers to the exploitation of a New Deal legislation called the Home Owners’ Loan Act to help refinance mortgages and prevent the unemployed from becoming homeless. Due to the inherent racism of the time, government agents characterized many neighborhoods as declining in quality or hazardous based on their personal prejudice. As a result, homeowners in these areas could not gain financial assistance to improve their properties, which fell further into dereliction, increasing segregation and promoting discrimination. Furthermore, urban forestry has been perceived as an amenity, increasing the value of homes with trees, pricing out any individuals trying to leave poorer districts. Therefore, NYC’s tree canopy distribution is not only meager but also inequitable, with some areas at 78% canopy cover and others only 3%.

Currently, the Parks Department manages 53% of NYC’s trees. The rest are other property types. Introduction 1065 would reclassify all of the trees as part of NYC’s urban forest and designate an agency to develop, report on, set goals for, and protect that forest. Specifically, it would require at least 30% canopy coverage by 2035. Maxwell urged the audience to contact their elected officials about the bill, remarking that “amazing people like Annel work in their offices,” also pointing out that anyone can become a citizen pruner.

Monastra’s installation focuses on photographs of trees that have survived various types of devastation, both natural and human-caused. She encouraged attendees to take postcards with images of the trees and send them to politicians.

To end the discussion, Randle turned to the audience for a brief Q&A. One spirited woman asked the panel for their opinion on her activist daughter, constantly “harassing her to plant trees.” “She travels from Seattle to New York on a train because she refuses to take a plane,” she went on, “and I wonder if you tell your mothers, do not travel any place under penalty of death,” finally querying which tree would be the best to plant. “I’m very careful of how I talk to my mom,” Maxwell answered, “but I give her a very hard time about her environmental habits.” Unfortunately, there is no easy answer, as tree species should be hand-picked for each specific area based on various conditions. Furthermore, a healthy urban forest would require a diverse array of trees. The Parks Department website features a tree species list, but residents can simply submit a request for more trees in their area through 311. One audience member also commented on the increase in environmentalist art submissions to her Prospect Heights gallery.

“Art allows us to see the world we want to see… That is one of the most beautiful effects… We can create worlds that don’t yet exist but that we would love to live in,” Salazar said at one point in the conversation. She’s working towards a climate-related art show at Sarah Lawrence College. Monastra is developing a project inspired by Phillip K. Dick and The Audubon Society’s report on birds and climate change to document climate-threatened birds.

Hernandez made clear that the council supplements the parks department but additionally invests in its own programs, like Trees New York’s Young Urban Forester Internship. The internship engages interns in various environmental career opportunities through work-based learning. Hernandez said her involvement in the internship program exposed her to a variety of trees as well as participatory budgeting in her community for the first time, “And guess what was one of the top things people wanted to see in their community? Trees, hands down.”

Maxwell’s organization, Forest for All NYC, will host a profusion of events for the second annual City of Forest Day on Oct. 14. Many will use arts to promote the urban forest and connect citizens to it. The programming will include musical and dance performances, mural painting, and sculptures.

Leave a Comment

Related Articles

Biden administration announces plans for up to 12 lease sales for offshore wind energy

Earth Day weekend 2024 celebrated in Brooklyn

Healthy harbor update: Billion Oyster Project hosts informative fundraiser in exclusive Williamsburg setting

Leave a Comment

Prospect Park

View MoreThe Brooklyn Daily Eagle and brooklyneagle.com cover Brooklyn 24/7 online and five days a week in print with the motto, “All Brooklyn All the Time.” With a history dating back to 1841, the Eagle is New York City’s only daily devoted exclusively to Brooklyn.

© 2024 Everything Brooklyn Media

https://brooklyneagle.com/articles/2023/09/26/conference-on-climate-hosted-by-brooklyn-botanic-garden-the-nature-conservancy-and-the-climate-museum/