All the world’s a stage: Matthew Gasda brings living room theater to Greenpoint

The Brooklyn Center for Theater Research heralds the off-off-broadway revival

GREENPOINT — In living rooms across Brooklyn, people barrel towards each other, like particles in an accelerator. They collide and spin apart, in directions hard to predict… Understandings emerge, and where understanding isn’t possible, a recognition of the human condition…

GREENPOINT — In living rooms across Brooklyn, people barrel towards each other, like particles in an accelerator. They collide and spin apart, in directions hard to predict… Understandings emerge, and where understanding isn’t possible, a recognition of the human condition…

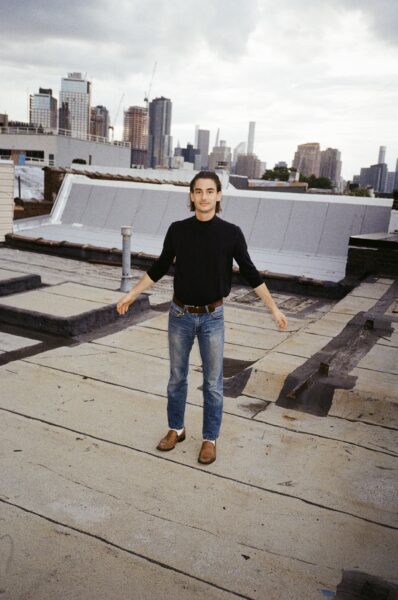

Sorry, what? I’m talking about independent theater. I’m talking about such independent theater that it makes other users of the term seem the first wave, sponsored by Big Oil and embezzlers. At the heart of the DIY revival is Matthew Gasda’s Brooklyn Center for Theater Research, where he’s the playwright-in-residence.

With over a dozen plays to his name, including an underground hit, Gasda’s rise to fame seems tied in part to skillfully preserving the feeling of a time and a place… and uncorking it at the exact right moment. Dimes Square premiered during the cultural lull of the pandemic in makeshift spaces, profiling a certain scene concentrated around keystone haunts in Chinatown. It caught the mainstream media’s eye and sold out repeatedly. It’s now been published, along with three other plays: Quartet, Minotaur and Berlin Story.