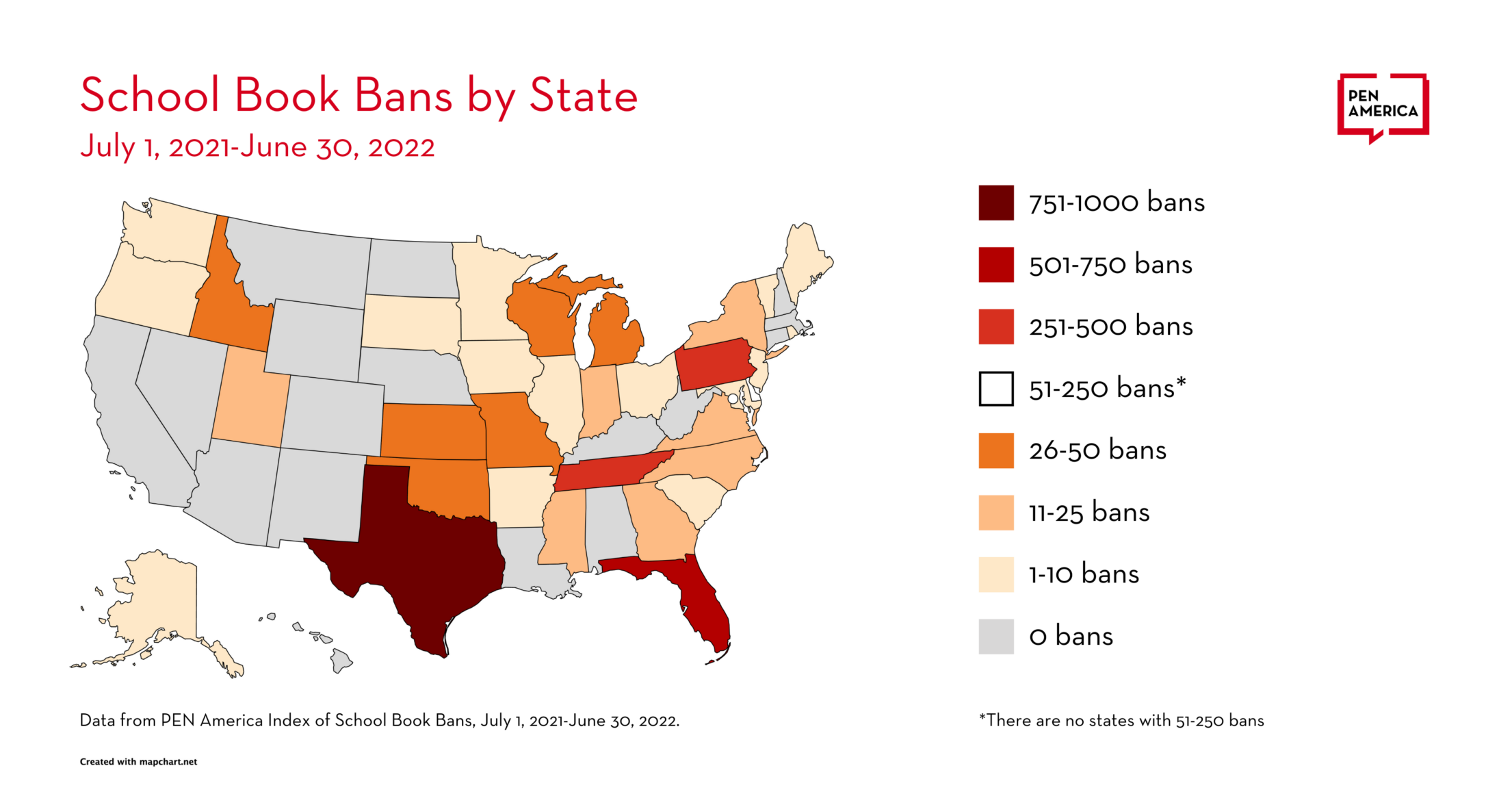

PEN America reported in the first edition of Banned in the USA (April 2022) that book bans had occurred in 86 school districts in 26 states in the first nine months of the 2021-22 school year. With additional reporting, and looking at the 12-month school year, the Index now lists bans in 138 school districts in 32 states. These districts include 5,049 schools with a combined enrollment of nearly 4 million students.

Total States and Districts with Bans

- States with Bans: 32

- Districts with Bans: 138

Total Bans by State

Rewriting the Rules

Beyond the school book bans documented in the Index and the efforts of various parties to see their implementation and enforcement, the past year has also seen attempts to change laws and school district policies in ways that make censorious challenges easier to file and impose. Even where such laws and policy changes have not been enacted, their chilling effect has been broadly felt.

Legislative Changes

The book-banning movement has operated in conjunction with legislative efforts to pass educational gag orders, all as part of what PEN America has referred to as the “ed scare”—a campaign to censor free expression in education. While the effort to constrain teachers has primarily progressed in state legislatures—as PEN America has documented, most recently in our August 2022 report America’s Censored Classrooms—and the effort to ban books has erupted mostly within local school districts, the two have increasingly merged, with some state legislators proposing or supporting bills that directly impact the selection and removal of books in school classrooms and libraries.

- Florida. Beginning in the summer of 2022, book bans in some Florida school districts were reportedly tied to the passage of the “Parental Rights in Education” law signed by Governor DeSantis in March 2022. Frequently referred to as the “Don’t Say Gay” law, this legislation prohibits classroom instruction on sexual orientation and gender identity in kindergarten through third grade, and also in grades 4–12 unless “age appropriate” and “developmentally appropriate” according to state standards. During the same legislative session, Florida lawmakers also enacted HB 1467, which, in the name of classroom “transparency,” modifies laws governing the selection and discontinuance of instructional materials in public school curricula and libraries, mandates elementary schools to list in a searchable manner all materials held in their libraries, and implicitly encourages greater public scrutiny.

This combination of a new law enabling tighter scrutiny and outside monitoring of curricular and book choices in classrooms, coupled with a new prohibition on instruction on certain topics, has done what was intended: it has created a chilling effect on teaching and learning. In anticipation of the law, books were removed in Palm Beach County in June 2022. Over the summer, more books were reported being removed from districts across the state, including a plan to “pause” classroom libraries entirely in Brevard, Florida. - Georgia. SB 226 passed in March 2022 and will change the way school libraries operate, removing some local control and consolidating power at the state level. The law vacates all school policies on book challenges and requires local school boards to create new policies for complaints, designed to make it easier to remove books with allegedly “offensive content.” Under this new law, school principals have only ten days to determine whether a book challenged for being “harmful to minors” by any parent or guardian will be removed or restricted from schools.

- Tennessee. SB 2247 expanded the State Textbook and Instructional Materials Quality Commission and required it to provide guidance for school libraries. It also created a statewide process for appealing decisions on challenged books to the state commission. These changes will make it easier for books to be banned from student access statewide on the basis of challenges filed in individual districts.

- Utah. HB 374, “Sensitive Materials in Schools,” was signed into law in March 2022 by Gov. Spencer Cox and prohibits from public schools certain sensitive instructional materials considered pornographic or indecent. It also requires the State Board of Education and the Office of the Attorney General to provide guidance and training to public schools on identifying sensitive materials, a process that must include parents deemed reflective of a school’s community. Although the law does not alter the definition of obscene materials in state statutes, it has been followed by guidance from the attorney general instructing schools to remove “immediately” any books deemed pornographic. The law has already had an impact, for example, in Alpine School District.

- Missouri. SB 775, an omnibus bill on sex crimes and crimes against minors, included an amendment that makes it a class A misdemeanor if a person “affiliated with a public or private elementary or secondary school” provides “explicit sexual material” to a student, defined in the bill as applying only to visual depictions of genitals or sexual intercourse, not written descriptions. The bill also contains exceptions for works of art, works of “anthropological significance,” and materials for a science or sexual education class. In the wake of the bill taking effect in August, a number of school districts in the St. Louis area removed books from their shelves preemptively, particularly graphic novels, which appear to be uniquely susceptible to challenge under the law’s provisions. Violation of the law could lead to jail or fines for teachers, librarians, and school administrators. Although police have said they will not enforce it, the law is nevertheless already having a chilling effect in the state.

Changing District Policies

Under the plurality Supreme Court decision in Island Trees v. Pico, banning or restricting books in public schools for content- or viewpoint-specific reasons is unconstitutional. To safeguard these rights, the ALA and the NCAC have developed best practice guidelines for book reconsideration processes school districts can adopt concerning library materials and instructional materials for which review is requested, whether by a parent, other community member, administrator, or other source. As discussed at length in Banned in the USA, these guidelines are intended to ensure that challenges are addressed in consistent, reasoned, fact-based ways while protecting the First Amendment rights of students and citizens and guarding against censorship.

In the 2021–22 school year, fewer than 4 percent of book bans tracked by PEN America were enacted pursuant to these established best practice guidelines aimed to safeguard students’ rights and protect against censorship. Instead, in numerous cases, school districts either ignored or circumvented their own policies when removing particular books. In other cases, districts followed policies that failed to afford full protection for freedom of expression—for example, by restricting student access to books while they are under review, by failing to convene a committee to review the complaint, or by not having the complainant complete the paperwork or read the whole book to which they were objecting as required by the stated policies.

In some communities where existing procedures are more aligned with the standards set forth in the ALA and NCAC guidelines, or where advocates for book banning have been stifled in their efforts, there have been new efforts to alter those policies and make the removal of books easier.

Such efforts often include a drive to change the “obscenity” determination used to ban books—usually without regard for the relevant legal standard. These changes have taken place in nearly a dozen districts, such as Frisco ISD in Texas, which in June revised its book policies to remove the existing standards of obscenity for materials and replace them with more stringent standards taken from the Texas Penal Code. In practice, this means that a sentence or image may be enough to get a book banned—and that book content will be evaluated without proper context. The inevitable result of the Frisco ISD and similar changes will be increased policing of content in books for young people, as well as the continued erosion of their right to access these materials.

Some policy changes have been advanced at the state level as well, with Texas leading the way. In April, the Texas Education Agency (TEA) announced new standards for how school districts should handle all content in their libraries. The Texas standards follow state representative Matt Krause’s October 2021 public letter “initiating an inquiry into Texas school district content,” as well as a public letter to the Texas Association of School Boards (TASB) from Gov. Greg Abbott in November 2021, asking schools to investigate why their libraries contained allegedly “obscene” and “pornographic” content in schools. Abbott did not provide any specific content examples. (It is worth noting that TASB has no power to change or even to recommend district policies.)

The policy recommendations from the TEA, compiled in response to the public letter from Governor Abbott, implemented four significant process changes of note, none of which comport with accepted best practices. The changes include the following:

- Singling out school library acquisitions for intensive review, more so even than the review process for curricular materials.

- Placing a ten-day deadline for reconsideration of challenged material. In an apparent acknowledgement that such a tight timeline will preclude a thorough review, the provisions simultaneously dropped the requirement that reconsideration committee members read the challenged material.

- Requiring librarians to host twice yearly review periods for parents to raise objections or voice concerns prior to accepting new acquisitions.

- Tying the consideration of material containing sexual content to the Texas Penal Code, point 3 of which states that a harmful material is defined as one “utterly without redeeming social value for minors.” If a book falls afoul of the state’s “harmful materials” standards—which are not aligned with Supreme Court jurisprudence defining obscenity in such works—it cannot be part of a school library.

While Texas has not made this policy mandatory for its school districts, the policy has begun to shape school library policies. By July 2022, at least two Texas school districts in Tarrant County had changed their acquisition policies based on the TEA’s model policy. For example, now if a book is challenged and removed in Carroll ISD, Texas, that book cannot be requested again for students for five years. In Keller ISD, this provision was changed to ten years.

The trend of district-level policy changes, which largely began in Texas, has picked up steam in other places too. For example, the school board in Hamilton County, Tennessee, accepted board policy recommendations from a special book review committee in March 2022, which removed a statement on the principles of intellectual freedom from the ALA’s “Library Bill of Rights.” This was a striking departure from the norm, as up until this year, it was a generally accepted standard that school board policies concerning acquisitions management and curricular development would reference or otherwise incorporate principles put forth by the Office for Intellectual Freedom of the ALA.

In another instance, Central Bucks County School District in Pennsylvania voted in July 2022 to reassign oversight of library collections from library and education professionals to a committee of the “superintendents designees”—politicizing a task

previously performed by library and education professionals well versed in sound acquisition principles and policies. The district further undermined its education professionals by moving to refocus collection acquisition strategies away from instructional needs—as determined by teachers, librarians, and other education professionals—toward potentially politicized decisions, such as evaluating books for sexual content using vague standards to determine whether a book should be placed in the library. In so doing, the district ran afoul of NCAC guidelines to ensure practices that “advance fundamental pedagogical goals and not subjective interests.”

From Kansas to Illinois, Indiana to Virginia, North Carolina to Florida, myriad efforts to implement and enforce censorious practices are effectively allowing some parents and citizens to constrain the availability of books for all students in their and other school communities. A raft of changes are making it easier to ban more books more quickly, undermining educators’ and librarians’ work and ultimately students’ rights to access information.

Preemptive Bans

The unrelenting wave of challenges to the inclusion of certain books in school libraries—whether promulgated at the urging of an individual community member, grassroots organization, or government official—has spurred another phenomenon: preemptive book banning. In April, May, and June 2022, PEN America tracked several cases where school administrators have banned books in the absence of any challenge in their own district, seemingly in a preemptive response to potential bills, threats from state officials, or challenges in other districts.

The most significant ban of this type occurred in Collierville, Tennessee, where a school district removed 327 books from shelves in anticipation of a state law that ultimately did not pass. Administrators sorted the books into tiers based on how much the books focus on LGBTQ+ characters or story lines; tier 3, for instance, reflected that “the main character of the book is part of the LGBTQ community, and their sexual identity forms a key component of the plot. The book may contain suggestive language and/or implied sexual interactions.” If a book reached tier 5, according to the sorting guidelines, “the books are being pulled.”

Other preemptive bans were responses to actions at the state level or in neighboring districts. For example, according to Texas media reports, bans in Katy ISD, Clear Creek ISD, and Cypress-Fairbanks ISD were the result of administrators responding either to what was happening in other districts or to an 850-book list compiled and circulated to education officials by Texas state representative Matt Krause.

Silent Bans and Other Restrictions

Finally, PEN America has tracked other instances of books included in banned book displays, or other disputed materials, being quietly removed to avoid controversy. Books are also being labeled or marked in some way as “inappropriate” both in online catalogs and on physical titles themselves. In the Collier County School District in Florida, for instance, warning labels were attached to a group of more than 100 books that disproportionately included stories featuring LGBTQ+ characters and characters of color. While these cases are not included in the Index because they do not meet PEN America’s definition of school book bans, these types of actions could have a chilling effect—applying a stigma to the books in question and the topics they cover—and they merit further study.

While several stories of preemptive and silent book bans have made it into the news or to the attention of PEN America, it is clear that mounting censorship and the punitive approach being taken to the enforcement of book bans is having wide ripple effects. The Supreme Court has sharply restricted viewpoint- and subject-matter-based restrictions on speech precisely because in addition to rendering certain ideas, stories, and opinions off-limits, such measures cast a wider chilling effect on expression. Given the rapid spread of book bans across the country, it seems inevitable that the resulting climate of caution and fear will result in a reluctance among teachers, administrators, and librarians to take risks that could affect their own employment, their budgets, their reputations, and even their personal safety. Emerging data, like a recent survey of school librarians by the School Library Journal in which 97% said they “always,” “often,” or “sometimes” weigh how controversial subject matter might be when deciding on book purchases is pointing clearly to these alarming trends.

The unprecedented flood of book bans in the 2021–22 school year reflects the increasing organization of groups involved in advocating for such bans, the increased involvement of state officials in book-banning debates, and the introduction of new laws and policies. More often than not, current challenges to books originate not from concerned parents acting individually but from political and advocacy groups working in concert to achieve the goal of limiting what books students can access and read in public schools.

As noted previously, the resulting harm is widespread, affecting pedagogy and intellectual freedom and placing limits on the professional autonomy of school librarians and teachers. The repercussions extend further, however, to the well-being of the students affected by these bans. Children deserve to see themselves in books, and they deserve access to a diversity of stories and perspectives that help them understand and navigate the world around them. Public schools that ban books reflecting diverse identities risk creating an environment in which students feel excluded, with potentially profound effects on how students learn and become informed citizens in a pluralistic and diverse society.

Book challenges impede free expression rights, which must be the bedrock of public schools in an open, inclusive, and democratic society. These bans pose a dangerous precedent to those in and out of schools, intersecting with other movements to block or curtail the advances in civil rights for historically marginalized people.

Against the backdrop of other efforts to roll back civil liberties and erode democratic norms, the dynamics surrounding school book bans are a canary in the coal mine for the future of American democracy, public education, and free expression. We should heed this warning.

Leave a Comment

Leave a Comment

Brooklyn Boro

View MoreNew York City’s most populous borough, Brooklyn, is home to nearly 2.6 million residents. If Brooklyn were an independent city it would be the fourth largest city in the United States. While Brooklyn has become the epitome of ‘cool and hip’ in recent years, for those that were born here, raised families here and improved communities over the years, Brooklyn has never been ‘uncool’.