Rent regulation reforms pit landlords vs tenants at hearing

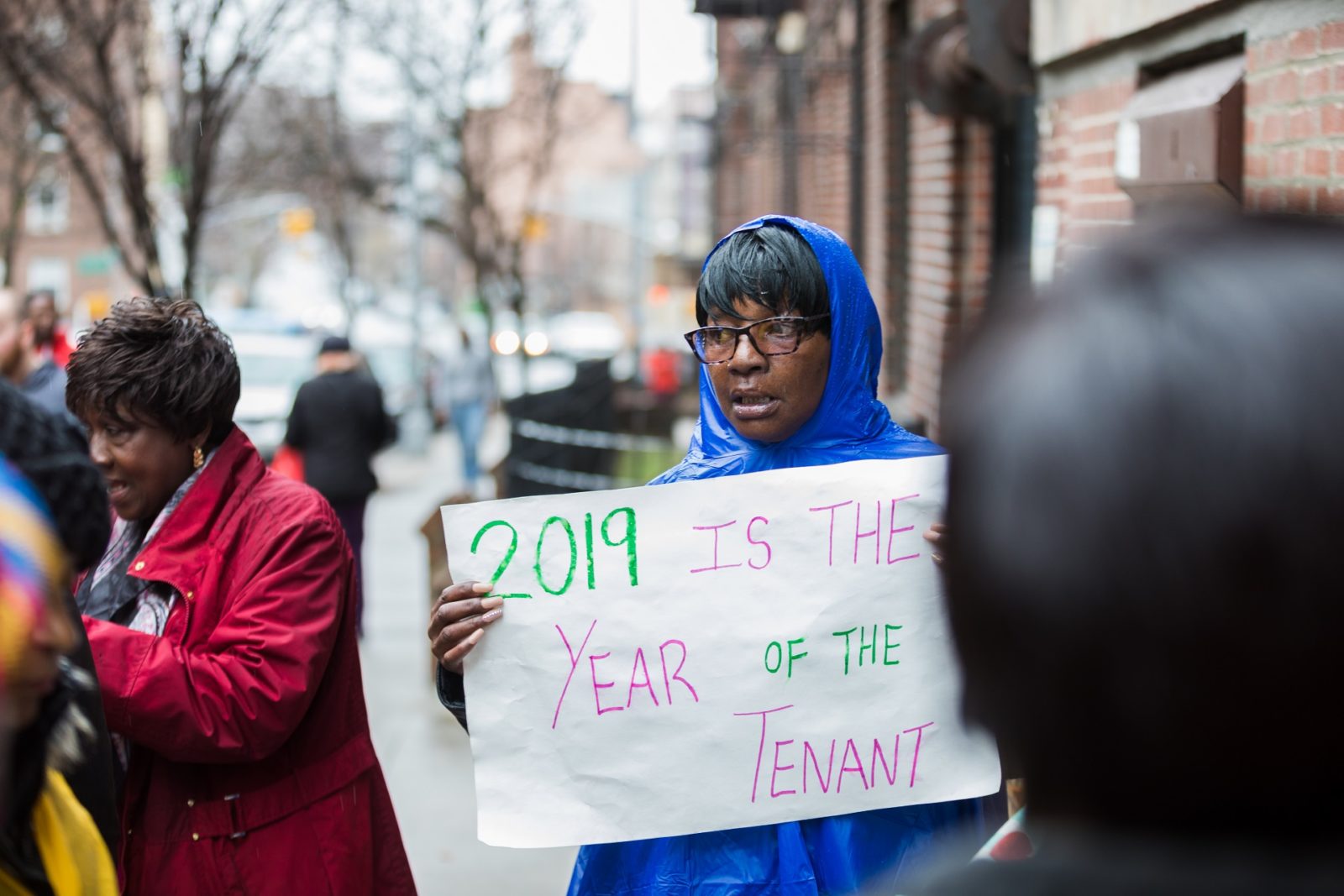

A loophole in rent regulation laws is pushing longtime, low-income residents out of their rent-stabilized homes, according to tenants and advocates who faced off against landlords at a hearing on Thursday.

State senators heard testimony during the seven-hour meeting on rent regulations at Medgar Evers College in Crown Heights. Legislators are considering a set of nine bills that could increase tenant protections and eliminate tactics landlords frequently use to raise rents in rent stabilized properties.

“Landlords are using the current laws to push working class communities out of their homes,” said Marcella Martinez, a resident of Sunset Park who lost her rent-stabilized unit in 2008. “This rampant abuse is mostly affecting people of color and people who can’t defend themselves. They want us out so they can tear the place down and build a place for rich people.”