OPINION: A tough look at American democracy

BAM and Think Olio Partner for Seminar Series

Throughout the course of human history, no population has been immune to the disorienting effects of internal strife. Here in the not-so-United States of America, we have reached one of those points in time that sees us talking at cross purposes and getting really angry at one another as a result. It’s not the first time we’ve found ourselves in this situation.

Sparks flew over the slavery question before and during and, most would say, since the Civil War. The rights of oppressed minorities and economically disadvantaged people have absorbed much of our attention in the years leading up to now. Today, in addition to those yet-unresolved issues, we’re also battling over the very soul of American democracy.

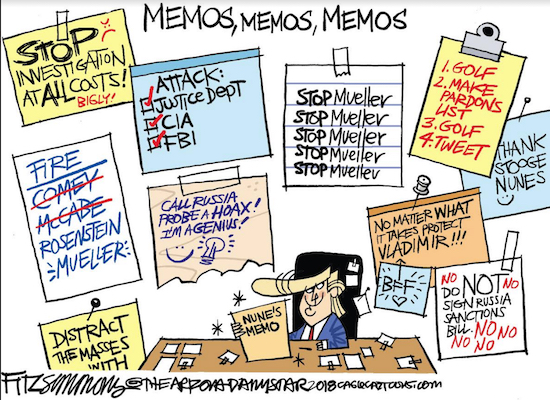

Over the past year, the indignant croak of a great wave of mostly non-minority (for now) Americans who feel like they’ve been left behind by progress has made itself heard. Their main cheerleader has taken up the cause, waging war against their enemies with a constant barrage of vitriolic tweets and campaign-style political rallies.