A charmed city, slated for ruin

Review & Comment

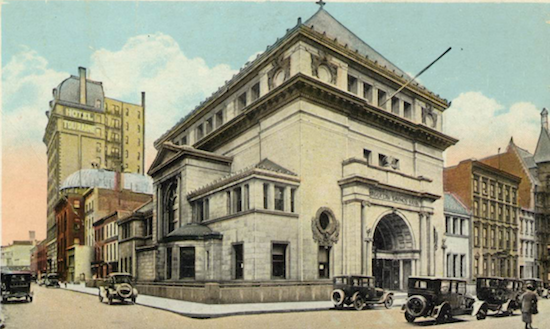

Screen Shot 2013-05-30 at 10.11.03 AM.png

“Any City gets what it admires, will pay for, and ultimately, deserves… we will probably be judged not by the monuments we build but by those we have destroyed.”

The New York Times Editorial Board uttered those fateful words in 1963 upon the demolition of a grand, renowned Pennsylvania Station. The soulless underground network of dreary tubes and uninspiring mall-like plazas that took its place was met with near-universal derision, continuing to the present day.