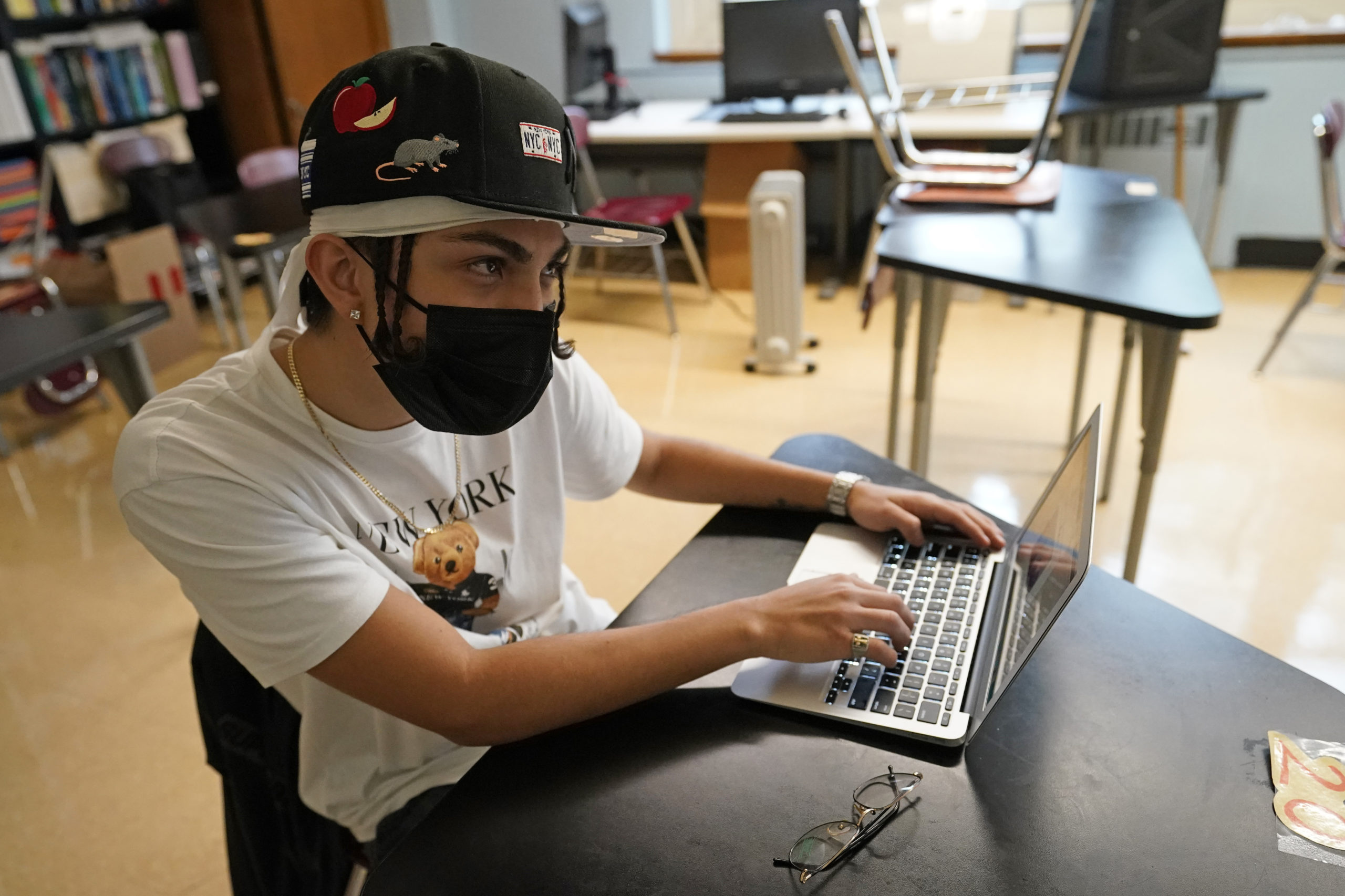

After massive NYC student data breach, here are steps you can take

New York City officials recently acknowledged that the personal information of about 820,000 current and former students was compromised in a cybersecurity lapse.

If you’re a caregiver wondering what that means for your family, here’s a guide with steps you can take to better protect your identity and your child’s, according to privacy experts.

First, the background: The company affected was Illuminate Education, which owns Skedula and PupilPath — platforms that crashed this winter as part of the breach, causing headaches for schools that rely on them for everything from tracking attendance to grades.

Brooklyn Boro

View MoreNew York City’s most populous borough, Brooklyn, is home to nearly 2.6 million residents. If Brooklyn were an independent city it would be the fourth largest city in the United States. While Brooklyn has become the epitome of ‘cool and hip’ in recent years, for those that were born here, raised families here and improved communities over the years, Brooklyn has never been ‘uncool’.