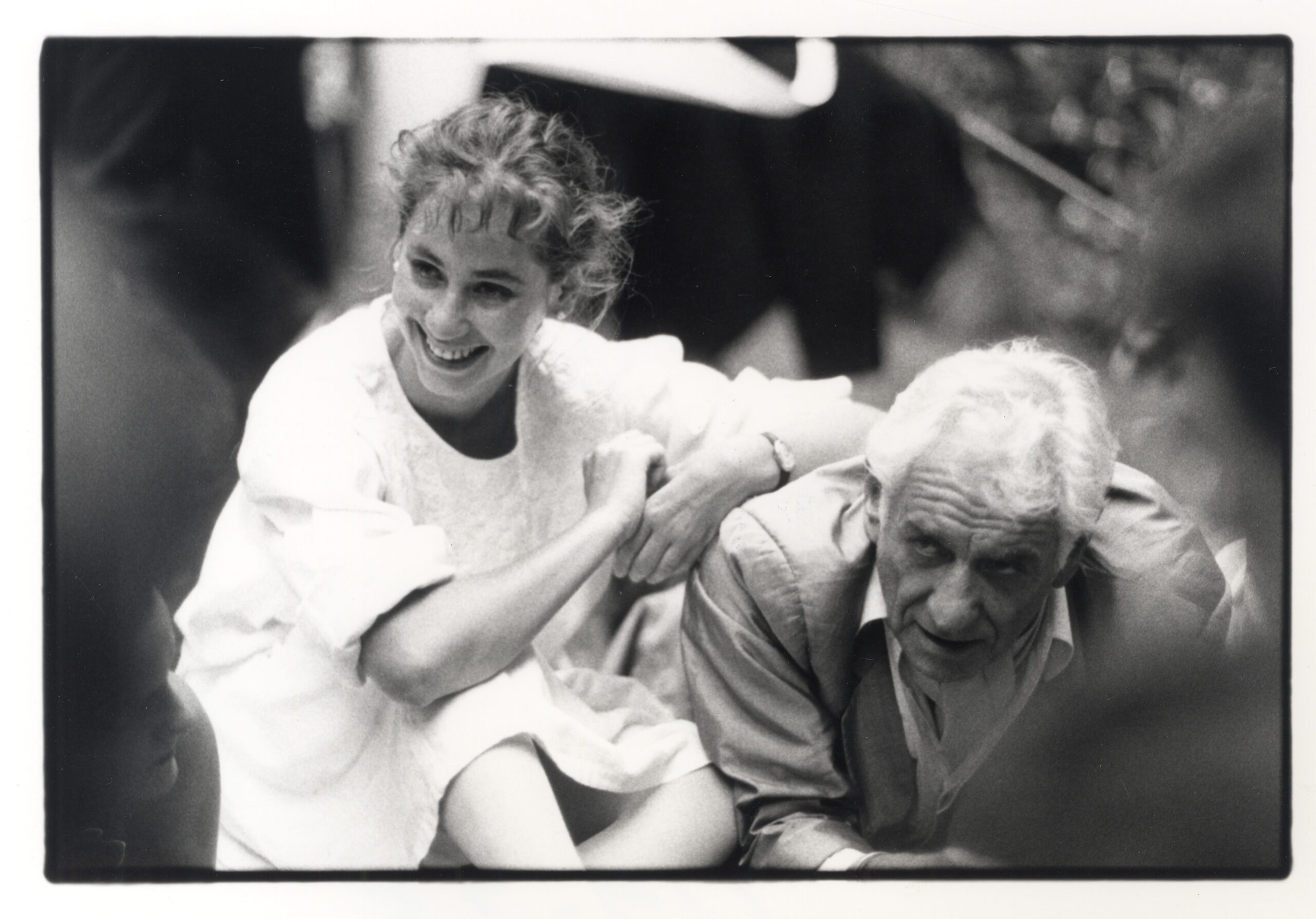

Leonard Bernstein’s daughter remembers: An interview with Nina, whose father rests at Green-Wood Cemetery

A Maestro Reposes in Brooklyn

Leonard Bernstein, although born in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1918, was the consummate New York artist. He was also a world-renowned pianist and conductor, notably with The New York Philharmonic. Bernstein composed numerous landmark scores, many of which underscore various facets of his adopted city. The violent romanticism of “West Side Story” serves as a counterpoint to the homesick sentiment of “Wonderful Town” and the war-torn melancholy of “On the Town”. The latter features a hymn to Gotham, “New York, New York,” a lyric of which is “The Bronx is up but the Battery’s down.” Points beyond is Brooklyn where, on a tranquil promontory in Green-Wood Cemetery, the beloved virtuoso’s gravesite overlooks the harbor he poignantly delineated with his score for the film “On the Waterfront.” Bernstein’s internment there is an elemental link connecting him to the borough. Funerary logistics, however, were not a major concern for a man who relished life, as Nina Bernstein Simmons explained during a recent interview.

“My father’s manager Harry Kraut, who himself was a Brooklynite, loved Green-Wood and arranged for the plot. He never wanted to discuss death and dying and the arrangements and plans. It was hard enough to even get him to write a will. He just didn’t want to discuss it. That’s where my mother was buried first in 1978. There were no special epitaphs, just names and dates. Very simple.”

All the Beautiful Sounds of the World — in Brooklyn

As a national treasure reposes in a national landmark, nearby environs brim with reminders of people and places that spurred a vitality no podium could fully contain. “I’m sure my father went for the occasional stroll through Prospect Park and The Botanical Gardens. He certainly had a number of recordings and performances in Brooklyn. His Brooklyn debut was with The Goldman Band in Prospect Park in 1943, months before his New York Philharmonic conducting debut. There were two other concerts in Prospect Park, in 1966 and 1967. The dates would suggest that those concerts were with The New York Philharmonic.”