Untreated mental illness handled by cops leaves gaps that Adams and critics are trying to fill

Mayor says he’ll instruct NYPD to get people to psychiatric treatment when they fail to meet their “basic needs.”

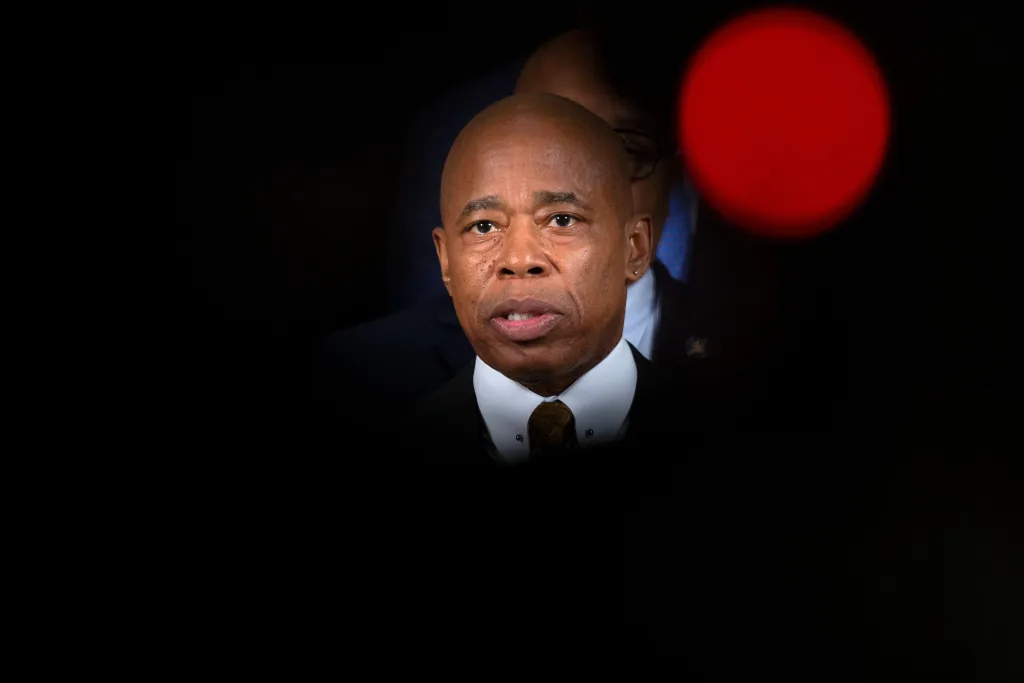

Adams speaking at City Hall on Tuesday. Ben Fractenberg/THE CITY

Photo: Ben Fractenberg/THE CITY

This article was originally published on Nov 29 4:59pm EST by THE CITY

In a scripted speech on a fraught issue, Mayor Eric Adams on Tuesday said the city’s police, mental health and other responders will step up measures to ensure people experiencing potentially dangerous episodes of serious mental illness get psychiatric evaluations and care.

Brooklyn Boro

View MoreNew York City’s most populous borough, Brooklyn, is home to nearly 2.6 million residents. If Brooklyn were an independent city it would be the fourth largest city in the United States. While Brooklyn has become the epitome of ‘cool and hip’ in recent years, for those that were born here, raised families here and improved communities over the years, Brooklyn has never been ‘uncool’.