If Biden decides not to run for reelection, he faces a big threat: Being a lame duck

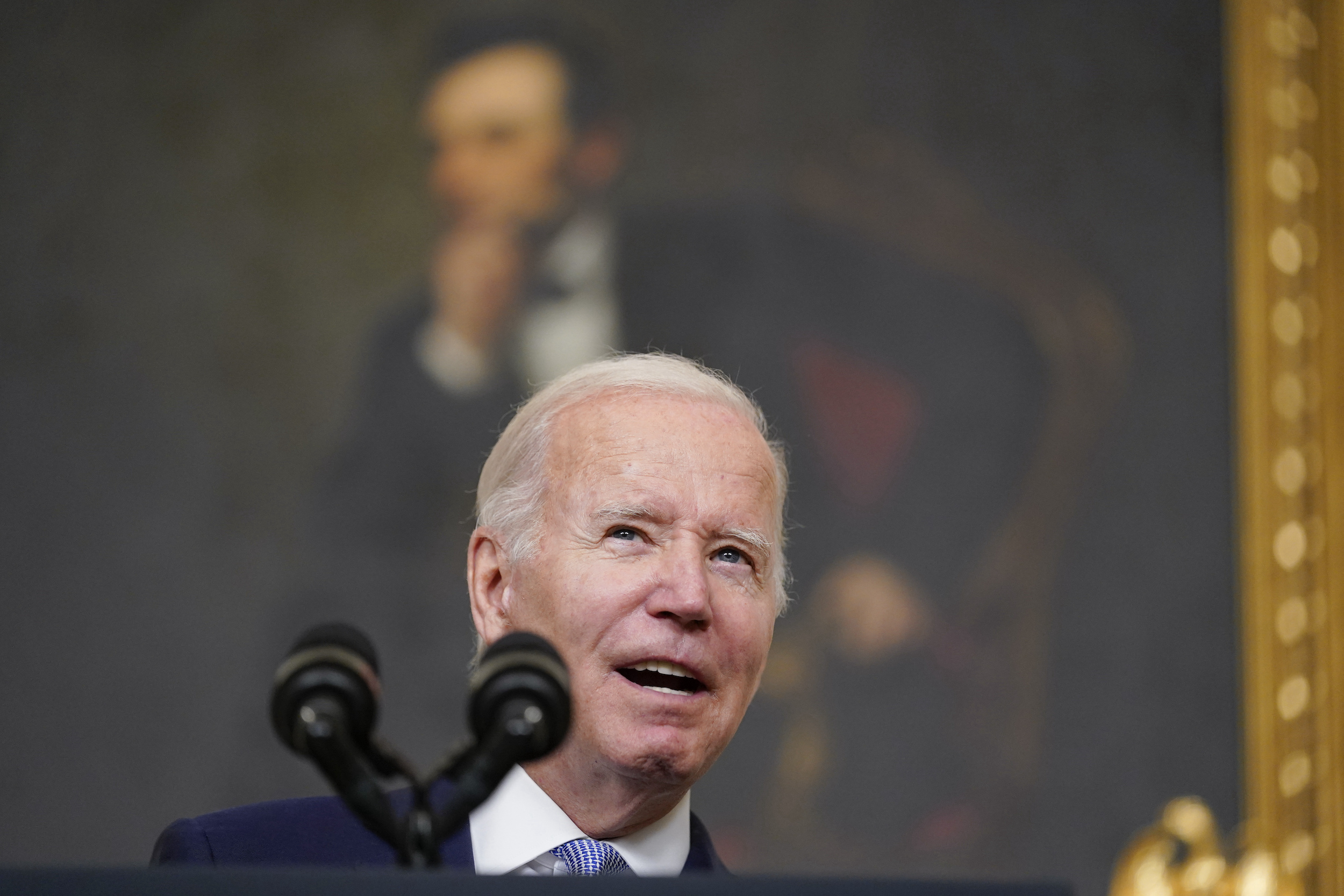

WASHINGTON, D.C. — Inflation: President Joe Biden spoke about “The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022” in the State Dining Room of the White House, on Thursday, July 28, 2022.

Photo: Susan Walsh/AP

As President Joe Biden’s approval ratings continue to hover around 40% and polls consistently show that most Americans do not want him to run for reelection, Biden’s spokespeople insist that he plans to run.

It would be more surprising if he did not run.

No eligible sitting president has declined to run for reelection since 1968. Announcing that he does not plan to run would make Biden an early lame duck and make it much harder for him to accomplish his goals.