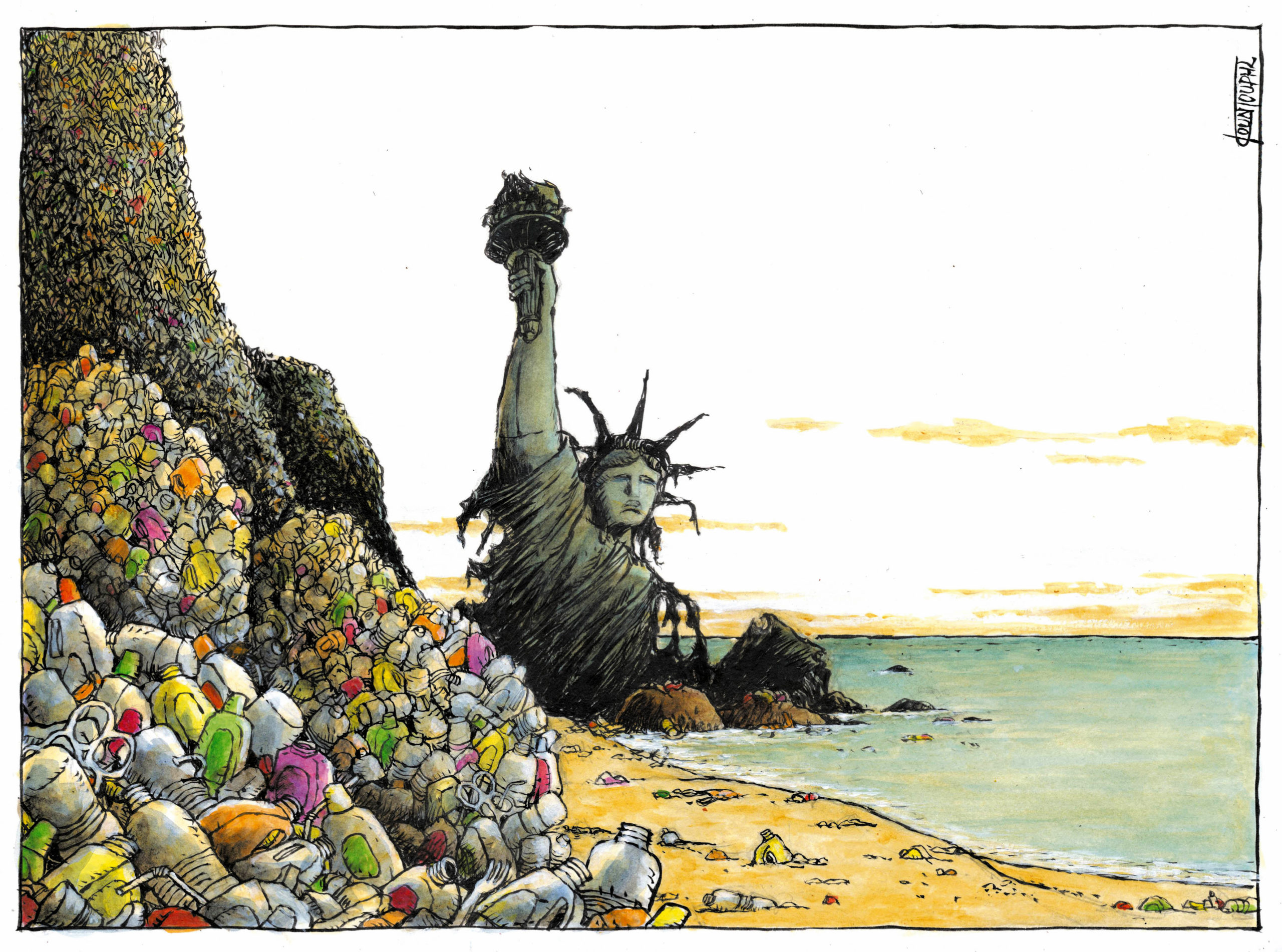

Two state initiatives tackle the difficult goal of managing plastics

There is hopeful movement on the recycling front, even though a national expert asserts it doesn’t go nearly far enough.

At the University at Buffalo, a new state Department of Environmental Conservation-funded research center will explore ways to make plastic recycling more effective. In Albany, legislators are ironing the kinks out of the Extended Producer Responsibility law, which provides incentives to manufacturers to use more sustainable and recyclable materials.

It’s been around since early 2021, but initially met with resistance and requests for exemptions. A new version of EPR is now working its way through the Assembly; an earlier Senate version is further along.