Happy Birthday, Campy!

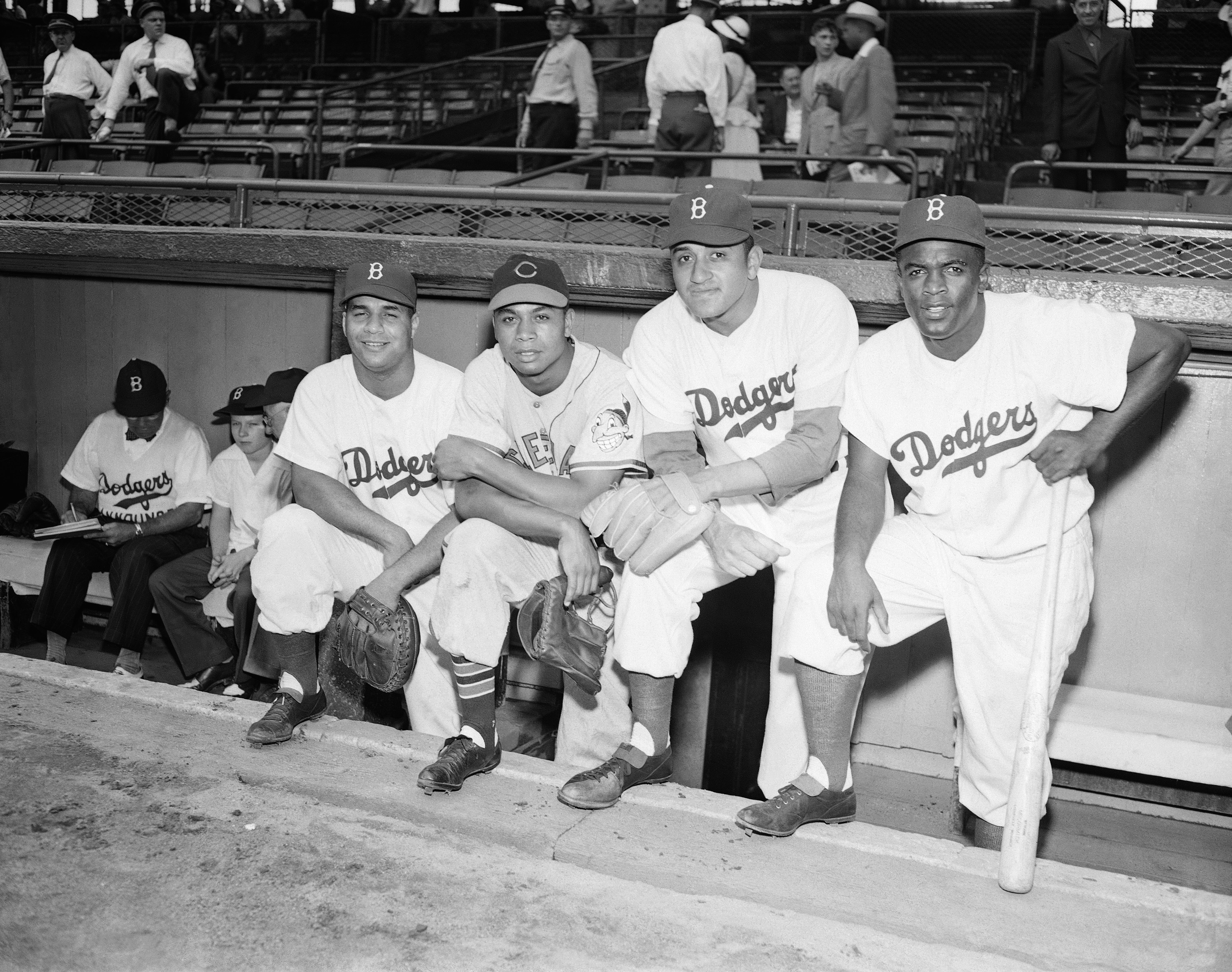

Roy Campanella’s stats were Hall of Fame stats. He entered the Hall in 1969. We’ll start with an overview of Campanella, the statistics man, but know that for a kid like me, he was ever so much more than numbers. His number 39 across his broad back made my heart race every time I saw it.

Roy Campanella was built like a tank turret. He was 5’9” tall and weighed 190 lbs. A base runner was not about to bowl him over trying to score. He hit 260 home runs in his almost 5,000 a bat. That means every 19 times he came to bat, a ball went into the stands. Watching him do it was a wonder. His body shifted, his right hip lowering as he smacked the ball like his bat was a club. Most of his shots were low trajectory laser beams. In 1950 he hit homers in five straight games, something to this day only four other Dodgers have done.

His career batting average was 283, but he had 1401 hits meaning he got a hit every 3x at bat. He batted over .300 a number of times in his career. He was MVP three times. He made the All-Star team every year from 1948-1957. According to “Baseball Fever,” Campy was considered a “superior” defensive catcher who was the best defensive catch of his time. Whew!

Brooklyn Boro

View MoreNew York City’s most populous borough, Brooklyn, is home to nearly 2.6 million residents. If Brooklyn were an independent city it would be the fourth largest city in the United States. While Brooklyn has become the epitome of ‘cool and hip’ in recent years, for those that were born here, raised families here and improved communities over the years, Brooklyn has never been ‘uncool’.