When Teachers Were Teachers

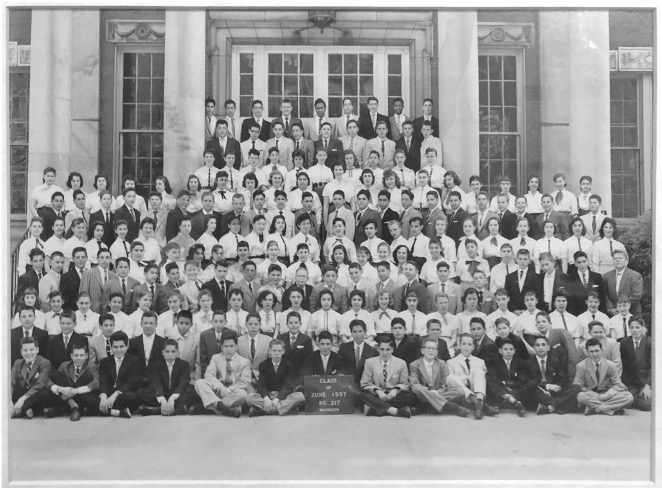

With so few teachers teaching in school, I’ve been thinking about the ones who taught me, and my generation. Mostly old-timers, they did it by the book, and it was a different book used for our kids today. Discipline was king and if you challenged the system too much you could end up, at least at PS 217 on stage, bent over, backside facing the Assistant Principal who was holding a canoe paddle. They were hard-core dedicated to the task, but in every batch was one or two who stood out for the wrong reasons, like these two.

Miss McNulty:

“Bones” McNulty was in a category by herself. Miss McNulty taught seventh grade math. She had gray hair, but she was so terrifying to look at, her hair could have been puce and I’d not have noticed. Miss McNulty was about five feet eleven inches tall. She looked to weigh about fifty-three pounds. Her fingers were as long as yardsticks, all boney with protruding joints, and blue veins coursing along her skin. When she wasn’t happy, she pointed a finger at you and lightning flamed from its tip burning holes right through your shirt into your chest. She was often not happy. The only thing I learned in seventh grade math was to duck.

Brooklyn Boro

View MoreNew York City’s most populous borough, Brooklyn, is home to nearly 2.6 million residents. If Brooklyn were an independent city it would be the fourth largest city in the United States. While Brooklyn has become the epitome of ‘cool and hip’ in recent years, for those that were born here, raised families here and improved communities over the years, Brooklyn has never been ‘uncool’.