Jim Crow’s creator, Thomas D. Rice, is buried in Brooklyn. But his blackface legacy just won’t die.

A stroll through Green-Wood Cemetery with Africana studies professor Zebulon Miletsky

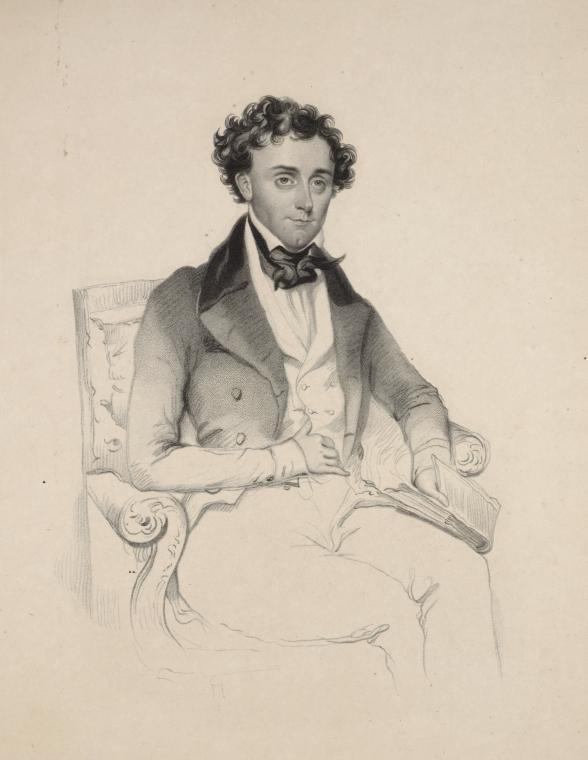

Popular early-1800s entertainer Thomas D. Rice didn’t invent blackface, but he is credited with popularizing it with the racist, career-defining “Jim Crow” song and dance that made him a star — and later lent its name to the segregation laws that were still in effect 100 years after Rice’s death.

Born in 1808 to working-class parents on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, Rice is interred on a hill in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery; today, his gravesite lies literally in the shadow of the great Steinway family’s.

We recently took a stroll to Rice’s burial place with historian Zebulon Miletsky, PhD, an assistant professor of Africana studies at Stony Brook University. The following is an edited transcript of our conversation about Rice’s — and New York’s — connection to minstrelsy, blackface and the centuries-long legacy of slavery.