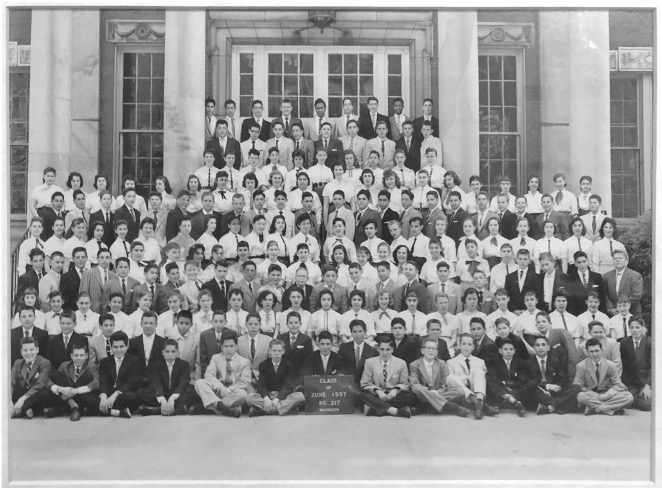

Revisiting my days in elementary school in 1950s Brooklyn

It was a long walk for short legs to get to school. About a block away, I heard the hum. It sounded like millions of bees hiving together. I gripped my mother’s hand — tightly.

It was a long walk for short legs to get to school. About a block away, I heard the hum. It sounded like millions of bees hiving together. I gripped my mother’s hand — tightly.

We approached the schoolyard, which opened up to a sea of bodies from which that hum was coming. I’d never seen so many kids in my life. The schoolyard was wall-to-wall children — literally — with some adults thrown in. And I knew not one. The sidewalk seemed to turn into wet cement; it became more and more difficult each time I put a foot down to pick it up again.

There were signs everywhere. It looked like the political conventions I’d watch with my parents on TV. Each sign, rather than announce the site of a state delegation, was a grade and class. My mother, quite good at such stuff, found my place all too quickly, said her goodbyes, and let go of me, or tried. I stuck to her like a suction cup to a board and cried like, well, like I’d never see her again. But, unlike me, she was made out of strong stuff, peeled my hand off hers, hugged me goodbye, and disappeared into the human ocean.

Brooklyn Boro

View MoreNew York City’s most populous borough, Brooklyn, is home to nearly 2.6 million residents. If Brooklyn were an independent city it would be the fourth largest city in the United States. While Brooklyn has become the epitome of ‘cool and hip’ in recent years, for those that were born here, raised families here and improved communities over the years, Brooklyn has never been ‘uncool’.