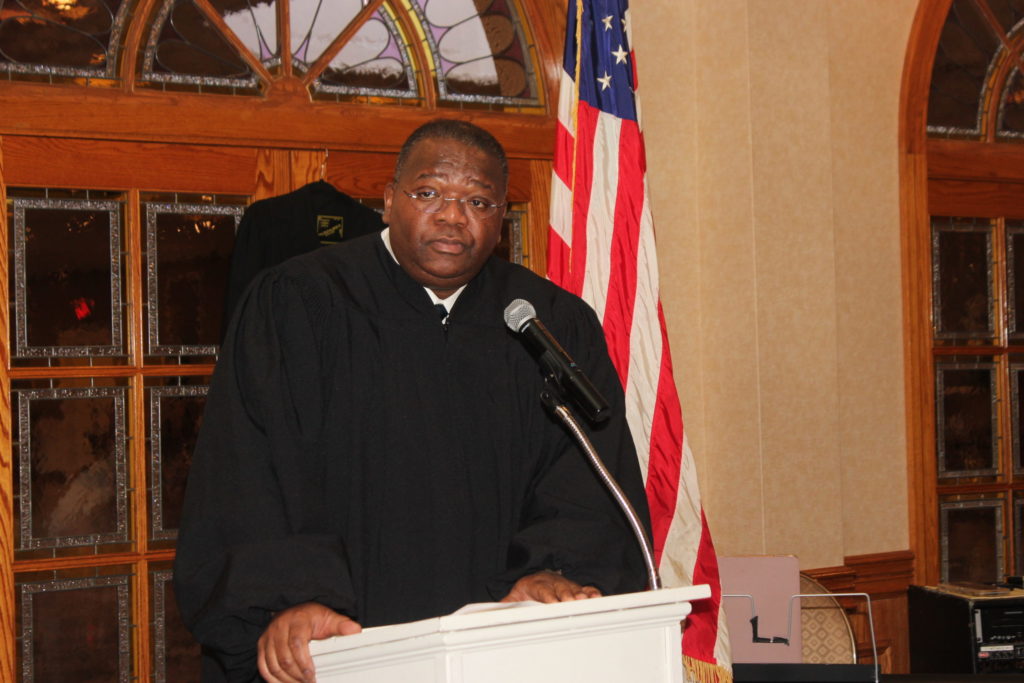

Justice Johnny Lee Baynes has died at 64 from COVID-19 complications

He’s remembered as a 'gentle giant' by the legal community

Hon. Johnny Lee Baynes, a judge in Brooklyn since 2005, died on Thursday of pneumonia related to the novel coronavirus outbreak that has plagued New York City and the world. He was 64 years old.

“He was a great man, he was great to work for,” said Hon. Jill Epstein, who served as Justice Baynes’ law clerk for nine years. “He pushed me, supported me and he was just the most gentle bear and lovely person. When people came into his courtroom, he wanted them to leave knowing they were treated with dignity and respect whether they were from a big firm or just some unrepresented pro se litigant. He tried to treat everybody fairly.”

Justice Baynes was born in a small town in Georgia and moved to New York with his family at a young age. When he was eight years old, his mother died, and he was raised largely by his sisters.

Brooklyn Boro

View MoreNew York City’s most populous borough, Brooklyn, is home to nearly 2.6 million residents. If Brooklyn were an independent city it would be the fourth largest city in the United States. While Brooklyn has become the epitome of ‘cool and hip’ in recent years, for those that were born here, raised families here and improved communities over the years, Brooklyn has never been ‘uncool’.