‘The year of the tenant’: Brooklyn’s biggest housing stories of 2019

2019: Year in Review

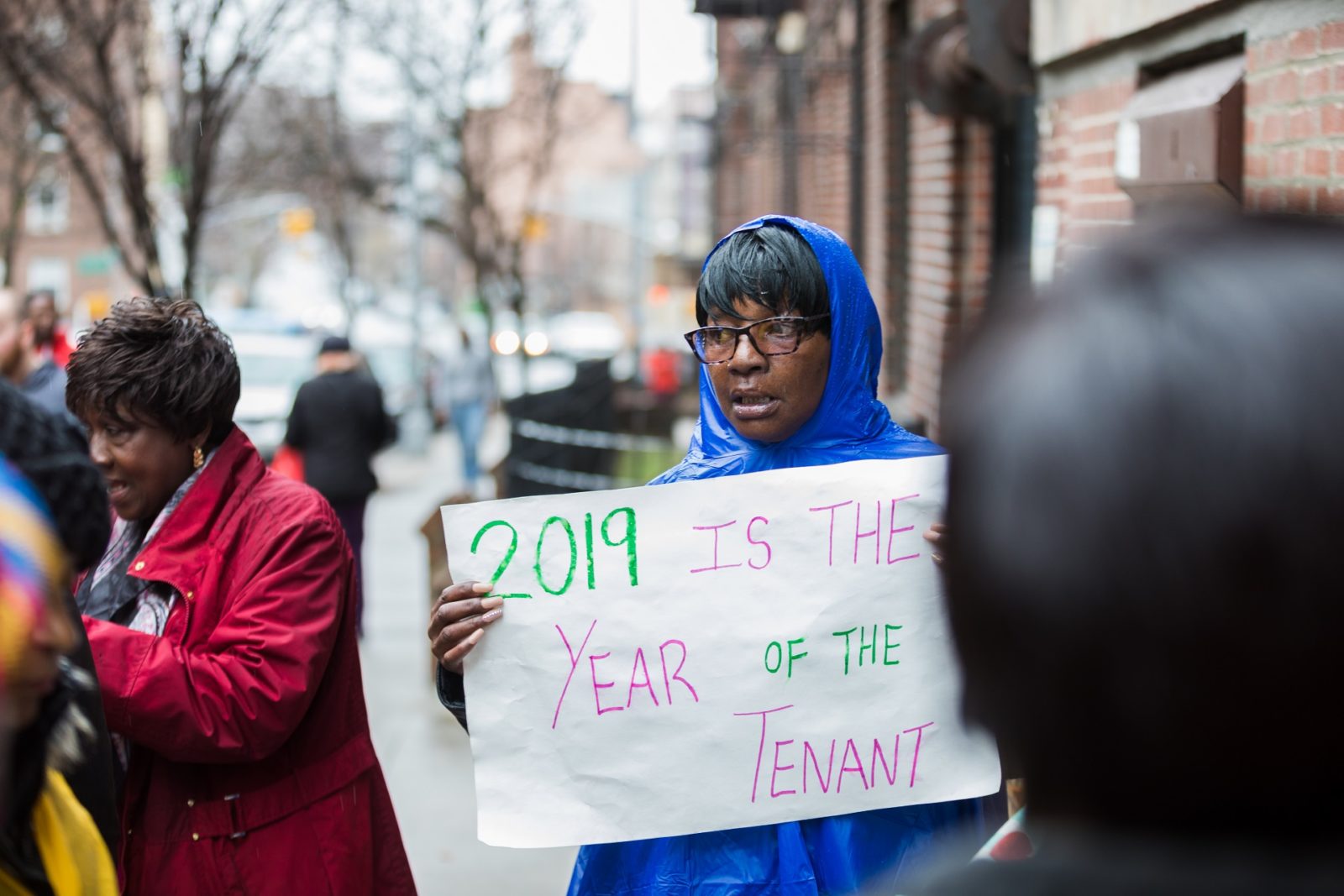

A Crown Heights tenant at an April protest. Photo: Paul Frangipane/Brooklyn Eagle

A lot happened in Brooklyn this year — from environmental policies to infrastructure changes to housing reform. We’ve wrapped up the key pieces for you in “2019: Year in Review.”

From rent reforms to deed theft to tenant activism, it was a historic year for housing in Brooklyn.

Here’s some of what happened:

Brooklyn Boro

View MoreNew York City’s most populous borough, Brooklyn, is home to nearly 2.6 million residents. If Brooklyn were an independent city it would be the fourth largest city in the United States. While Brooklyn has become the epitome of ‘cool and hip’ in recent years, for those that were born here, raised families here and improved communities over the years, Brooklyn has never been ‘uncool’.