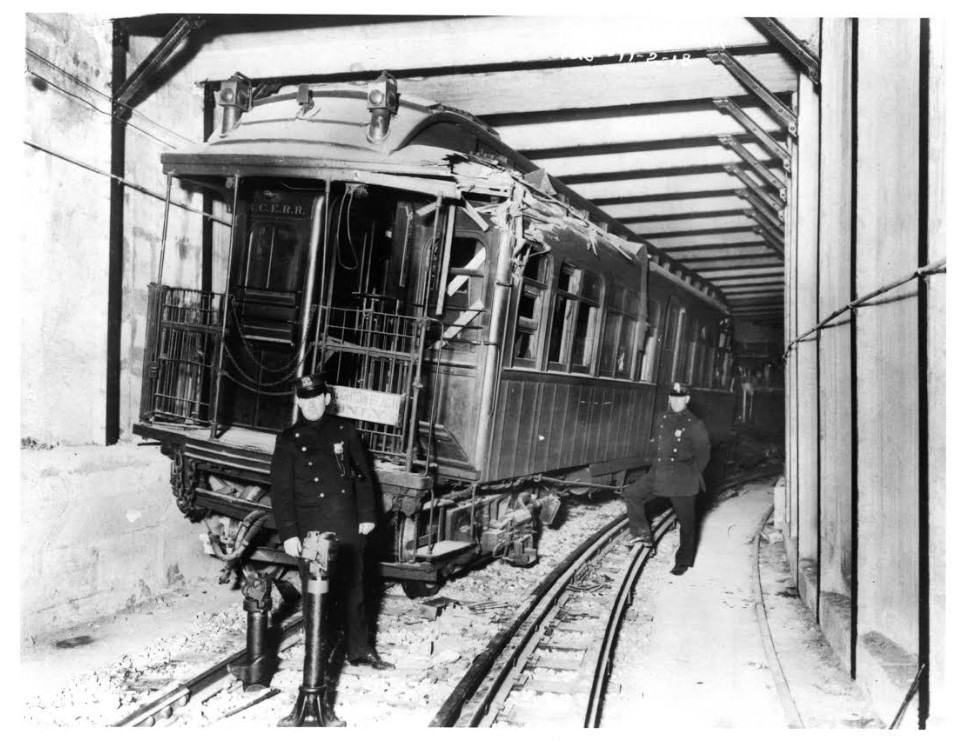

101 years later, deadliest subway crash in New York remembered

A permanent plaque has been installed to honor victims

A year after the 100th anniversary of the deadly Malbone Street subway wreck, which killed 93 people and injured more than 200 others, a bronze plaque was installed on Friday on the wall of the outdoor plaza leading to the B and Q lines’ Prospect Park station, near where the deadly crash took place.

If you can’t find “Malbone Street” on a map, there’s a reason for that. The street had such a bad connotation after the wreck, which was the worst disaster in New York City transit history, that its name was changed to Empire Boulevard. One block of Malbone Street still survives under its original name in Crown Heights.

“With this plaque and street co-naming, we are honoring the victims of the horrific Malbone Street Wreck, and honoring our history, so New Yorkers for generations to come can learn what happened here,” said Borough President Eric Adams. Adams advocated for and helped fund the plaque’s installation.