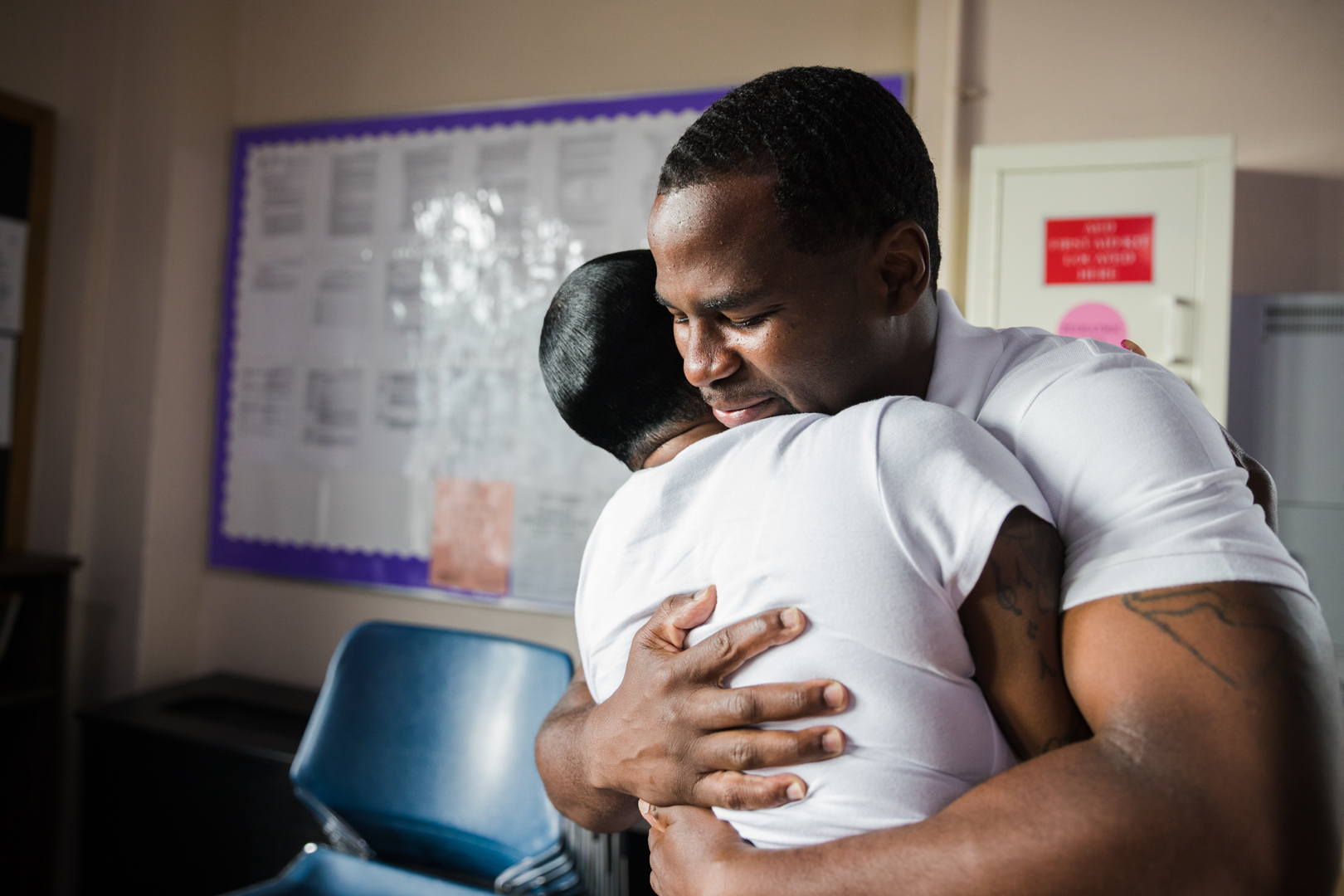

They met as children. Now married, she’s been visiting him in prison for nearly 20 years.

Loved ones of the incarcerated could benefit from a program that makes family visits easier and reduces recidivism — if lawmakers pass it.

Saturday, 5:00 a.m. — Kaywonda Banks sits in an unmarked olive green van parked near Barclays Center, two full bags of food and house supplies between her legs and her 8-year-old son in the seat next to her.

This is the starting point for her four-hour, roughly 100-mile trip into the mountains of New York, where her husband, Javon, is incarcerated at the Otisville Correctional Facility.

Maintaining her marriage and providing a father figure for her children means regularly skipping sleep and traveling upstate — without owning a car. For the single-income mother of three, it’s a $500-a-month toll.

Brooklyn Boro

View MoreNew York City’s most populous borough, Brooklyn, is home to nearly 2.6 million residents. If Brooklyn were an independent city it would be the fourth largest city in the United States. While Brooklyn has become the epitome of ‘cool and hip’ in recent years, for those that were born here, raised families here and improved communities over the years, Brooklyn has never been ‘uncool’.