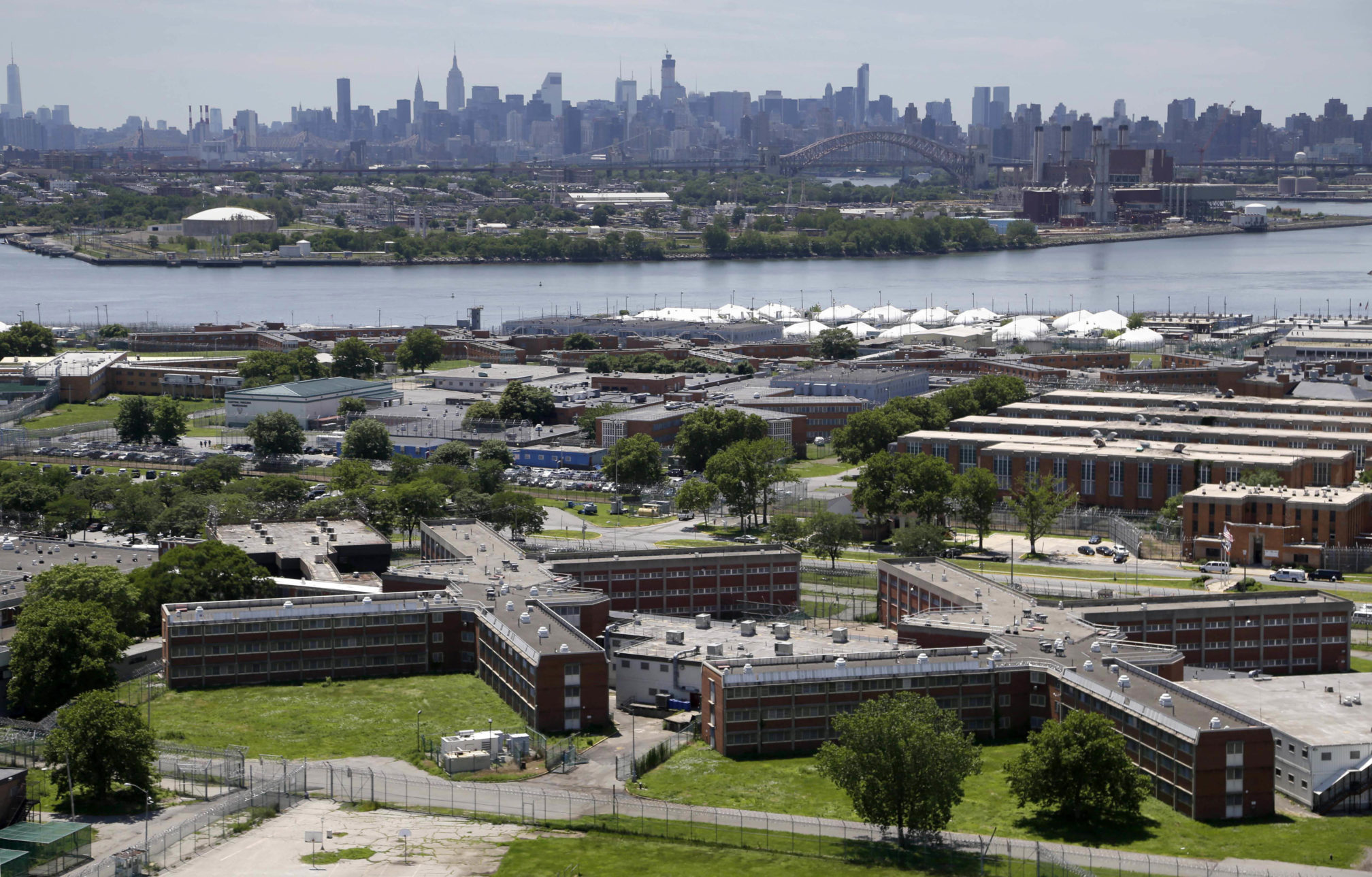

OPINION: I worked at Rikers Island. It’s time for better jails.

In the oft-referenced words of Dostoevsky, a society can be judged by entering its jails. I have seen Rikers Island from the inside and it does not speak well of us.

For five years, I was a clinical social worker there, rising to be an assistant chief in the Mental Health Department. I support the current plan to close the eight active jails on Rikers, including through a rebuilt, better-designed facility in downtown Brooklyn, where I have been a lifelong resident. Here’s why.

When I worked at Rikers, the population hovered at 22,000. Today, the census has dropped to under 7,300, and crime is at historic lows. With the city seeking alternatives to jail for people with mental illness, and bail reforms to be implemented in January, that number will be further reduced. The city’s ultimate goal is no more than 4,000 people in jail — remarkable for a city of almost 9 million.