The reinvention of Industry City: Nearly 400 years of history

There's a long tradition of land-use battles over 35 acres of land in Sunset Park.

As is often the case during cease-fires, a quiet tension hovers over Sunset Park’s shores as opposing forces prepare for battle. In past centuries, Dutch settlers fought Lenape natives, or British soldiers marched on American revolutionaries for control of the soil — but the land wars of Brooklyn today are between developers and community for control of the zoning.

In early March, City Council member Carlos Menchaca and Community Board 7 Chairperson Cesar Zuniga wrote a public letter to the developers of Industry City — a 35-acre complex of 16 looming factory loft buildings along the Brooklyn waterfront — asking that they postpone their application for a massive rezoning until the fall. The proposed changes, first made public back in 2015, would add more than one million square feet of new commercial development including hotels, an academic space and retail stores. Days later, U.S. Reps. Jerrold Nadler (D-NY) and Nydia Velázquez (D-NY), along with New York State Sen. Zellnor Myrie (D-Crown Heights), wrote a similar joint letter.

Zoned In:

An ongoing series exploring the changing rules of New York City zoning and real estate, spotlighting important moments shaping the borough from more than 370 years of history. Stories in this series:

This all took place a few weeks after the implosion of Long Island City’s doomed Amazon deal. Industry City had been an alternate site the tech giant had considered before settling on Queens, and now Brooklyn politicians were transmitting the similarly impassioned concerns of Sunset Park residents: Such a grand boost in development would “supercharge the displacement and gentrification that is undermining Sunset Park’s affordability and blue-collar job base,” the joint letter said.

The narrative of forcing out the same working-class people Industry City’s tenants are meant to employ very closely echoed the anti-Amazon arguments. The developers acquiesced, agreeing to wait until September. This was considered a small victory for a collection of community groups and urban scholars who had voiced their concerns about the “hyper-gentrification” that would undoubtedly result.

Despite the good timing, it’s not possible to assign direct cause and effect to the developer bowing to the wishes of the community for more time. Before anyone had an inkling of the PR nightmare awaiting Amazon, Industry City’s executives had been courting Sunset Park residents in order to gain public support for the rezoning by presenting their plans in as transparent a manner as they felt possible. Their community interactions were indeed of a rare type that went beyond the city requirements of developers in terms of communicating with community members. Andrew Kimball, chief executive and public face of Industry City, presented plans of the potential expansions in a series of town halls hosted by Community Board 7, and in October 2017 a public scoping meeting was held where community members were encouraged to bring forth their concerns.

In that packed room, dozens of local business owners, workers and residents — both for and against the development — gave their testimonies of grave concern or strong support. Many Industry City tenants exclaimed that improvements to the complex had boosted their own businesses, and thus they believed strongly in increasing the development’s scope.

Some were concerned with a lack of attention paid to environmental impacts. What green engineering practices would Industry City consider to prepare for potential coastal flood zone changes? Would they make commitments to developing renewable energy practices in the zoning plan? Most of all, those in the crowd raised the question of residential displacement: Would people be priced out of their rents by the gentrifying effect of new developments or perhaps a loss of working-class jobs? How far and to what extent would that impact be felt — and would the rezoning plan examine the various effects beyond the immediate border of Industry City’s walls?

However, when Industry City released the latest version of its application, none of these suggestions appeared to have been incorporated into the plan. So when local politicians halted the process, it seemed a reprieve — though momentary — for a collection of community groups and urban scholars who had voiced their concerns about “hyper-gentrification.”

One key detail that justified Menchaca’s “forcing their hand,” as he put it, was that the developer’s application submission would have automatically set in motion the ULURP — that same land-review process that Amazon had tried to sidestep. Menchaca and Community Board 7 had received technical assistance funding for an independent expert evaluation in advance of the ULURP, and the study hadn’t yet concluded. Planning experts have now spent the summer assessing both the possible extent of rent displacement by the rezoning and the potential scale of business growth if the zoning is left as is.

As Menchaca explained previously to the Brooklyn Eagle, beginning the ULURP in March would have limited the amount of time for appropriate fact-finding and forced the community to enter negotiations without all of the information they needed. To the developers, he asked: “What is the rush?”

Menchaca has a devoted following in Sunset Park. He speaks often with great confidence about the rights of community in the face of development and does not shy away from critiquing corrupt real estate practices and rich landlords. As the area’s representative in the City Council, he wields tremendous power — on land-use issues, the council traditionally votes with the member whose district is affected. If adhered to, this precedent of “member deference” means Menchaca could unilaterally squash the plan.

Industry City and its early 20th-century factory lofts straddle the bay side of Third Avenue along Sunset Park. A group of real estate capital investors, notably Chelsea Market co-developers Belvedere and Jamestown, bought a stake in the five million square feet of industrial and commercial space in 2013 for an unknown sum from Brooklyn real estate owners Ruby Schron and Avrohom Fruchthandler. Millions of dollars in private investment into the property has brought more than 5,000 new jobs to the neighborhood to date, and — by subdividing large-scale open floor plans into small units — tripled the number of businesses in the complex, according to Industry City’s spokesperson.

According to Kimball, Industry City prides itself on taking “great strides to ensure those opportunities stay close to home” and maintaining an open dialogue with the community. This refers to partnerships with local organizations like the Southwest Brooklyn Industrial Development Corporation or work programs like their Innovation Lab, which boasts a mission of creating a path up the “economic ladder” intended on engaging locals.

By many accounts, the new Industry City has been a great success. A New York native, Kimball’s redevelopment experience most recently includes eight years leading the revival of the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Industry City seems a natural progression.

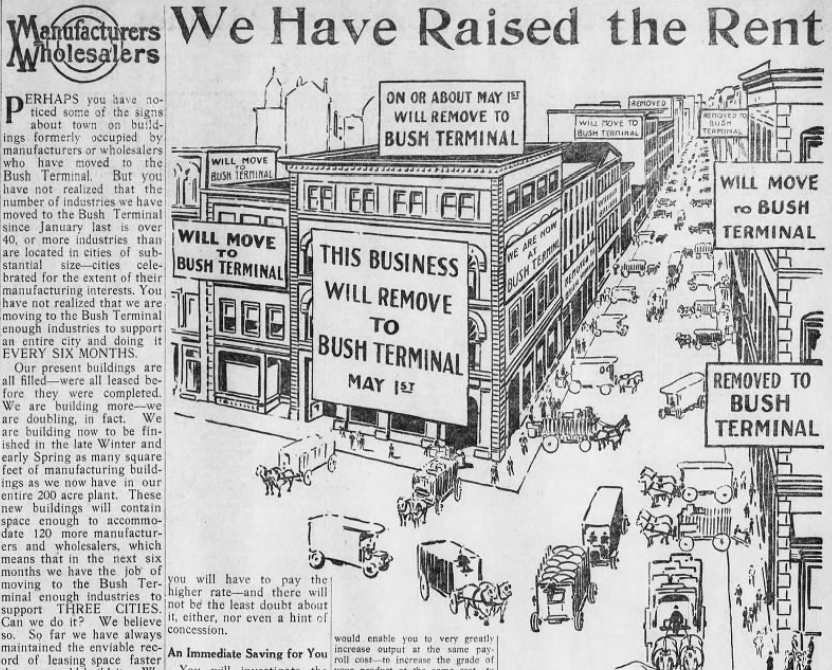

Kimball promises that the rezoning will bring an additional 15,000 jobs to Sunset Park and a variety of new uses for spaces that have been thoroughly industrial since the earliest construction in 1911. The ads that ran in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle from that year regarding the Bush Terminal, as this development was originally called, made uncannily similar promises about the updated use of the waterfront. That massive construction project would address the needs of a modern shipping economy and bring thousands of new jobs to 20th century Brooklyn.

This tract of land on the Brooklyn waterfront has an unusually storied past. It was included in one of the first land patents ever created in Brooklyn, when in 1636 European settlers Jacques Bentin and William Bennett bought 936 acres of waterfront farmland “extending from the vicinity of Twenty-eighth street, along Gowanus Cove and the bay, to the New Utrecht line “ from a Lenape sachem, or chief, named, Ka. American rebel soldiers exchanged fire with British invaders on its hills during the Revolutionary War, and for the century afterward it was boat-accessible farmland and seashore.

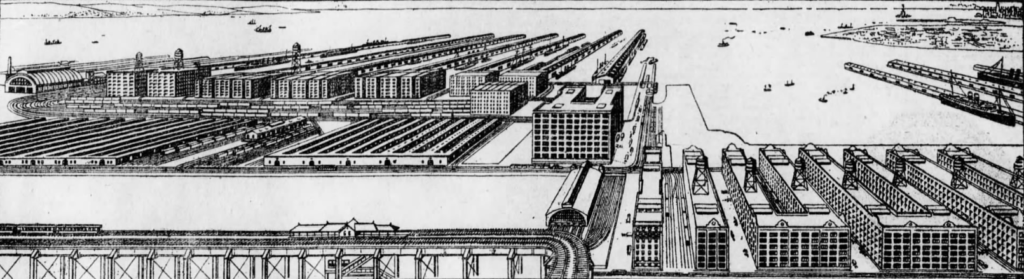

In 1872, after a fire burned down his first location in the Gowanus Creek, entrepreneur Rufus T. Bush opened a crude oil refinery at the foot of 25th Street. His firm, Bush & Denslow, became a main competitor with, and was eventually purchased by, Standard Oil. Irving T. Bush, Rufus T.’s son, opened a warehouse on the site of that refinery in 1890, which he developed and scaled up into the massive complex that was the Bush Terminal. “Why not bring them to one place, and tie the ship, the railroad, the warehouse, and the factory together with ties of railroad tracks?” he had asked himself. The logic and language parallels that for Industry City’s proposed “innovation economy.”

Beyond his enormous financial gains, the physical scale of his development was so grand that the U.S. Navy appropriated use of their facilities during both World Wars. Bush died in 1948 even more wealthy and successful than his father.

The nationwide decline of urban manufacturing after World War II started in areas exactly like this. In 1951, the Bush Terminal Company began referring to the complex as Industry City, after its association as one of America’s first “Industrial Parks.” Yet shipping operations steadily declined, and a business consortium led by billionaire hotelier Harry Helmsley purchased the 35-acre lot in 1963. The remaining parts of the original Bush Terminal were acquired by the city of New York, presumably because nobody else wanted it. Shipping came to a complete halt by the end of the decade and during the city’s fiscal crises following 1974, the docks were solely a popular dumping ground for illegal industrial toxins like “oil sludge,” leading to the vicinity being designated a hazardous environmental waste site.

Prostitution, drug dealing, and body dumping also became part of the area’s quotidian life. Despite these challenges, Industry City remained mostly occupied in this era due to the large scale of the buildings, which set it above most other urban manufacturing zones in New York, and it became known as being New York’s “other” Garment District. Helmsley owned and leased its spaces until 1986, and he appears to have sold it to the Ruby Schon-led group at this time. They defaulted on a $300 million loan in 2011 before current ownership structure was established, although that problem was supposedly resolved. It was 2012’s Hurricane Sandy that woke them up to outside investment and management.

New York City designated manufacturing areas like this one “Industrial Business Zones,” an effort to protect urban industry from total extinction. According to local politicians and many community members, manufacturing fits not only the “fabric of the neighborhood” but provides job security for diverse populations who live there today.

Developers like Kimball see this view of the economic ladder as archaic in 2019, and in their opinion urban industry is now “much broader” than manufacturing. Even the law confounds: In what zoning calls manufacturing, Industry City can currently allow for some retail but not others (“soft” versus “hard” retail), or film and television studios, which are not widely accepted as manufacturing but otherwise a desirable tenant of the 21st-century economy. Almost as a warning, Kimball has pointed out that the current zoning would allow for commercial offices.

Despite Kimball’s forward-looking philosophy, communities like Sunset Park see the existing complex as a reliable source of blue-collar jobs, and to this day its IBZ designation protects it from the perils of outsized land speculation. Simply put, to some the zoning works quite well as it is.

In terms of creating more jobs and businesses, Industry City has had clear success innovating within the restrictions of its current zoning, or “as-of-right,” and so there’s an argument for its ability to grow in its current form. Their Innovation Lab program has recently published statistics on the number of people they have trained and those placed in jobs at their tenants’ businesses. By most accounts, the current situation is quite successful.

As developers, though, the most recent investors in Industry City have never had any intention of leaving the zoning as is.

Developers are always looking toward the future, and in this view, Industry City sees introducing new kinds of businesses to industrial spaces as providing new economic ladders to climb — a result of what Kimball calls the “innovation economy.” To achieve this, and to meet the demands of a modern commercial real estate market, Industry City must rezone, in their view. This goal was built into the rationale and very business model behind their initial investments, which have been extensive.

Similar large-scale projects like the city-owned Brooklyn Navy Yard don’t often happen without a public entity’s support, but this development does not rely on public money. A developer’s philosophy, ideally based on extensive analysis of real estate business in New York, is not likely to change. And in many arguments they may have a point. “I am very proud of the fact that we have more manufacturing at Industry City today than we have had in 40 years,” said Kimball on a recent tour of the facility.

There are also some nice perks in this rezone for Industry City: Not only would it expand the base of tenants it can accept, it would also be able to secure more financing for new constructions and renovations based on an increased perceived value of rezoned land. The development proves its worth to banks by increasing the income of this once-defaulted property so the owners can borrow money to develop it further.

This is the business of zoning and real estate in New York. The perceived future value of property has driven the change of landscape since the colonists arrived and started “buying” land grants signed by Native Americans. A more comparable (and recent) historical parallel in terms of zoning at this spot would be in the late 19th century, when Brooklyn’s expansion into the Town of Flatbush would bring about the question of converting acres of agriculturally zoned lots into urban lots as the city grew at an enormous rate. Almost no one doubted that urban lots with buildings were worth more than high-yield, vegetable-producing “market gardens,” despite their usefulness to the nearby city full of hungry people.

Thanks to the powers of real estate speculation, agricultural land in today’s Sunset Park disappeared in tracts when it suddenly became attractive to hawk-eyed urban developers poised for zoning change.

Some owners of these lots and tracts of land — including descendants from the same Dutch settlers of the 17th century — lobbied to get the zoning changes. Clearly the expanding city was a success and many people made a lot of money — such growth is inevitable, if we’re lucky.

Yet historians argue the gardens were all eliminated before they had a chance to prove their own economic clout in the modern city by the promise of immediate cash gains. So they mourn the potential loss of a uniquely Brooklyn brand of urban market gardens, arguably providing fresh produce for generations of expanding populations, not to mention the added value to communities at large.

Simply put: We could have had lots of cheap, delicious, fresh produce, if only we hadn’t built all of those apartment buildings. This sounds pretty great, but of course there is no way to measure something that never happened.

With the land-review process poised to begin again later this month, the community awaits Menchaca’s findings on how the zoning proposal would affect displacement, congestion and climate change. How those findings would be incorporated into any future zoning plans and what kind of dialogue Industry City has with the community is anybody’s guess. In 2019 we are entering new territory in Brooklyn waterfront real estate, an era of technological and social advances and economic puzzles to solve.

The most novel part of this particular zoning war is the power of the community voice, which was enough to give billionaire developers some pause to listen more closely. Industry City has claimed their level of engagement with Sunset Park is “unheard of” in the real estate world. These kinds of “firsts” seem so often to happen in Brooklyn, and so armed with expert information, a 21st century-style development dialogue will proceed into new territory on an ancient slip of waterfront property.

Joseph Alexiou is a journalist, tour guide and author of Gowanus: Brooklyn’s Curious Canal. His local writing credits include Curbed, Gothamist, New York Magazine, and The New York Times. He lives in Prospect Heights and plays in Gowanus.

The Brooklyn Eagle presents “Zoned In,” an ongoing series exploring the changing rules of New York City zoning and real estate.

Over the coming months, we’ll speak with the activists who fought the battles of the ’80s, ’90s and ’00s. Expert planners and historians will put today’s fights over land use in context, spotlighting important moments shaping the borough from more than 370 years of history. And we’ll talk to the people of Brooklyn whose lives are being shaped by these rezonings each and every day.

Follow along, and see the latest here.

Is there a topic you’d like us to explore in this series? Let us know here.

Have you or your family, or your business, been affected in some way — good or bad — by changes in zoning? Let us know here.

Correction (Sept. 13 at 5 p.m.): A previous version of this story erroneously stated that Superstorm Sandy occurred in 2013. It was 2012. The story has been corrected, and the Eagle regrets the error.

Leave a Comment

Leave a Comment