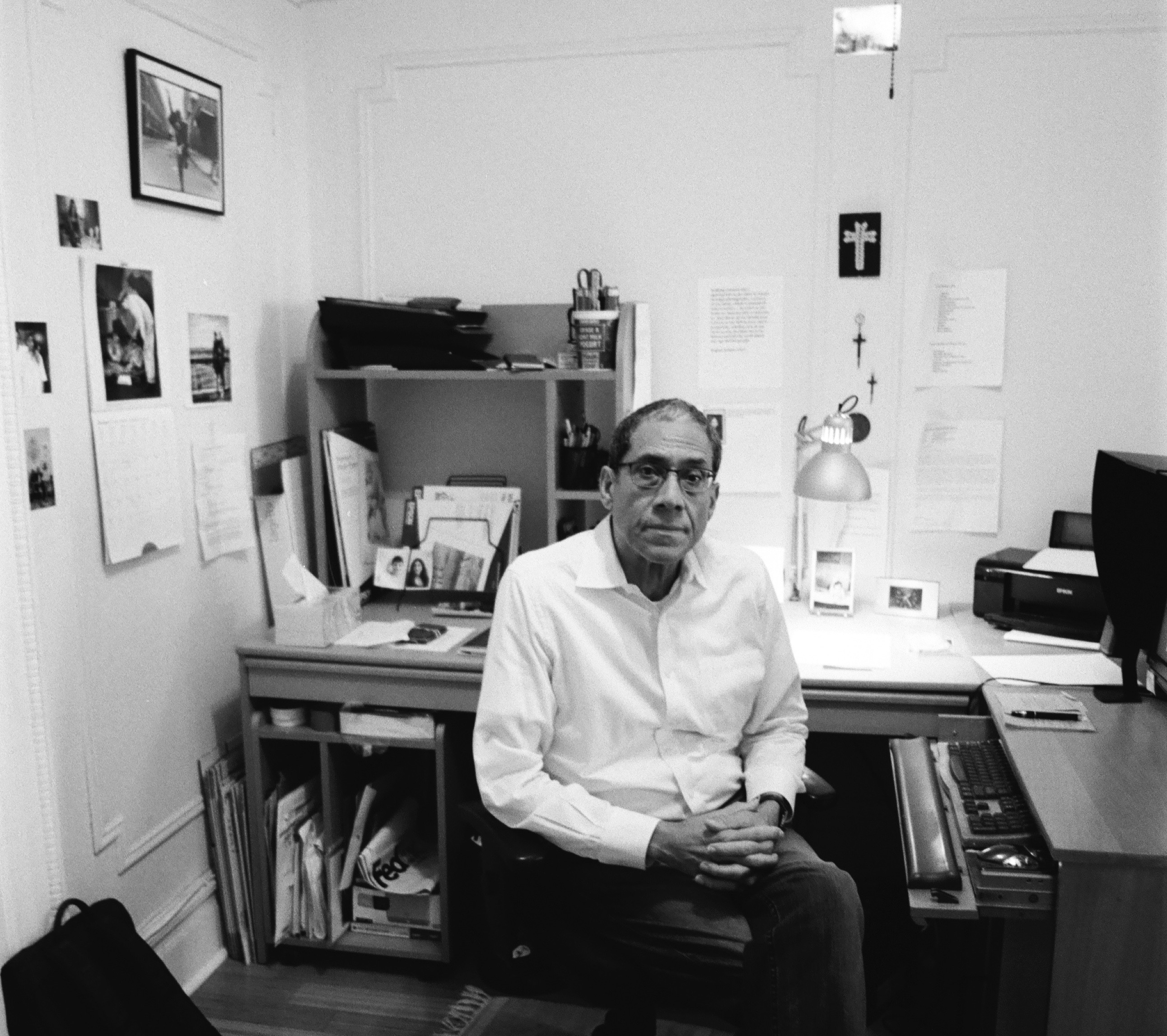

Practiced patience: The photographs of Joseph Rodriguez

The photographs of Joseph Rodriguez offer a glimpse into the people and places not usually on view in gallery spaces: youth detention centers in Northern California, the gangs of East LA, sex workers in Mexico, the community in Spanish Harlem.

This month, the photographer’s work will be on view at Photoville in Brooklyn. The exhibit will showcase photos from his book “Spanish Harlem: El Barrio in the ’80s,” which depicts day-to-day life in the neighborhood from the mid- to late-1980s. In December, Rodriguez is releasing his next book: “Taxi Journey Though My Windows,” which features photographs he took as a cab driver in New York City in the 1970s and 1980s.

Rodriguez, a former drug addict who was once incarcerated on Rikers Island, is from Brooklyn. He was raised by his mother, who — when he was 9 — married an abusive heroin addict. The absence of a stable family structure, and a father in particular, is a recurring theme in his work.

Brooklyn Boro

View MoreNew York City’s most populous borough, Brooklyn, is home to nearly 2.6 million residents. If Brooklyn were an independent city it would be the fourth largest city in the United States. While Brooklyn has become the epitome of ‘cool and hip’ in recent years, for those that were born here, raised families here and improved communities over the years, Brooklyn has never been ‘uncool’.