Tens of thousands of dollars go to lobbyists in the fight over city’s jail plan

With the possibility of a bigger jail coming to Boerum Hill, wary neighbors are turning to an age-old lifeline: cash.

Neighborhood opponents of Mayor Bill de Blasio’s plan to rebuild and expand a jail in Boerum Hill have spent more than $30,000 on a “boutique government affairs” lobbyist to sway the city toward building a smaller Brooklyn lockup — or toward scrapping the plan altogether. Not to be outdone, national group JustLeadershipUSA, which supports the borough-based jail plan, spent $32,500 of their own on a lobbying firm in support of their campaign to close Rikers.

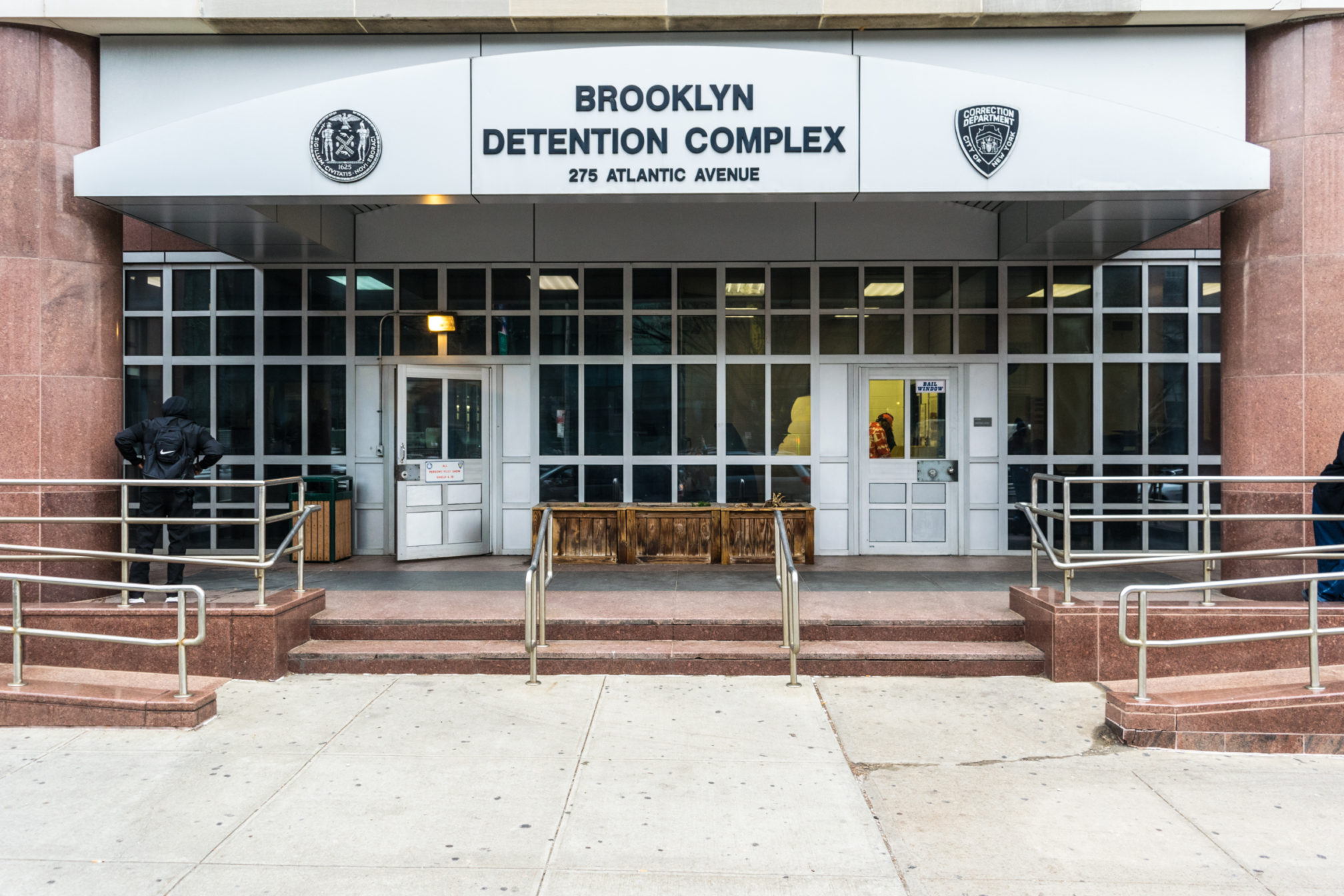

Residents of Boerum Condominium at 265 State St. — a 210-foot-tall, 21-story luxury apartment building directly across from the current 11-story Brooklyn Detention Complex — pooled $11,350 in late 2018 to hire to G. Fontas Advisors Inc., a lobbying group run by George Fontas. The subject of the payment was “Brooklyn Detention Complex ULURP Process,” according to city lobbying records. ULURP stands for Uniform Land Use Review Procedure, the process the city uses when developers — including the city itself — want to build something taller or bulkier than existing zoning allows.

The luxury building at 265 State St. itself upset some neighbors — when it was being developed — who thought it was too tall for the historically brownstone neighborhood.