L-train shutdown provokes questions, anxiety at Williamsburg town hall meeting

Citi Bike could be a key part of the solution to subway and roadway congestion during the coming L-train shutdown — but expansion of the bike share system is not currently part of the city and state mitigation effort, residents discovered at a well-attended community meeting Wednesday night.

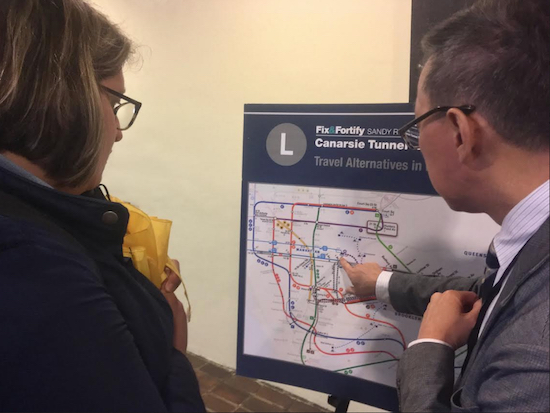

MTA will shut down L-train service between Brooklyn and Manhattan next April — inconveniencing hundreds of thousands of commuters every day. The state agency and its city transportation counterparts have devised mitigation efforts that include carpool-only hours on the Williamsburg Bridge and a bus-only 14th Street in Manhattan, but Citi Bike, which is the nation’s most-used bike share system, is not currently in the plan.

Motivate, which runs Citi Bike, does not have docking stations anywhere east of Bushwick Avenue — an irony, considering that the meeting itself was held at Progress High School, which is just east of the Citi Bike “no-go” line.