Book Review: To Know Brooklyn is to Remember Abraham & Straus

Brooklyn BookBeat

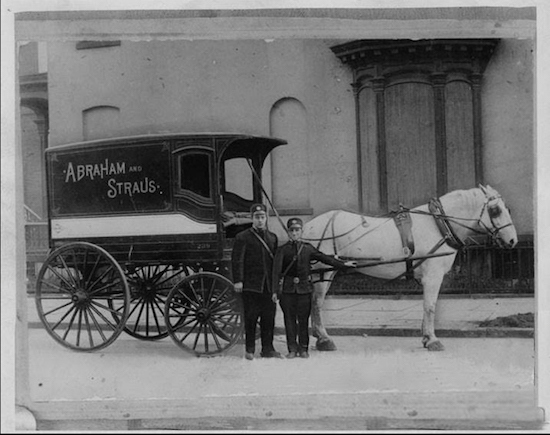

Once upon a time, Fulton Street was the shopping capital of Brooklyn with grand emporiums to lure its citizens “downtown.” Along the blocks from Flatbush Avenue to Smith Street stood Loeser’s, Namm’s, Oppenheim Collins, Martin’s and Abraham & Straus, all multilevel department stores that attracted and embraced their customers with a plethora of desirable wishes.

Outside, huge display windows advertised temptations available inside. Once beyond the revolving doors, fashionably dressed salesclerks beckoned under the gaze of floor walkers. Smiling guides at tall information stands dispensed a litany of departments and destinations, directing shoppers to a bank of elevators and escalators off to the side. For those distracted by so many choices, lunch rooms offered comfort food and relaxation.

The undisputed queen of this merchandising Mecca ruled as Abraham & Straus, a welcoming source of necessities for the home and its inhabitants. From its bustling Fulton Street entrance, customers hastened past cosmetics and jewelry to the golden elevators in the middle of the building. Other shoppers drifted in from Livingston Street or even up from the basement entrance and the IRT subway platform.

Brooklyn Boro

View MoreNew York City’s most populous borough, Brooklyn, is home to nearly 2.6 million residents. If Brooklyn were an independent city it would be the fourth largest city in the United States. While Brooklyn has become the epitome of ‘cool and hip’ in recent years, for those that were born here, raised families here and improved communities over the years, Brooklyn has never been ‘uncool’.