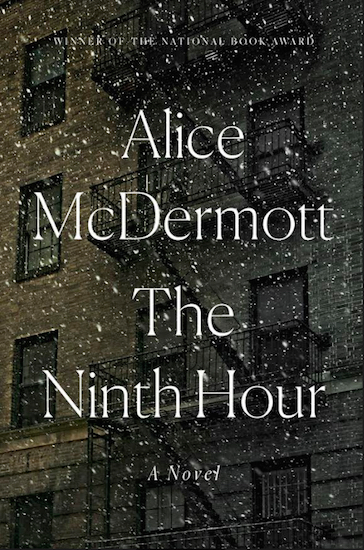

Alice McDermott captures bygone era of Brooklyn

Brooklyn BookBeat

Alice McDermott’s stunning new novel, “The Ninth Hour” (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), does for contemporary literature what “Call the Midwife” has done for public television. Both recall an earlier era when women in religious orders operated as de facto social service agencies, nursing the sick, clothing the poor and doing whatever they had to do to keep destitute families together.

The novel begins on a somber note. A handsome young Irish immigrant named Jim has killed himself for what appears to be the most capricious of reasons. He was a man, we are told, who believed “that the hours of his life … belonged to himself alone.” Later, darker aspects of his personality will emerge.

In the meantime, his suicide drives the plot forward, casting a shadow over the lives of his widow, Annie, and their unborn daughter, Sally — and requiring a cover-up in their Brooklyn, New York, parish because the Catholic church at the time considered suicide a sin.

Brooklyn Boro

View MoreNew York City’s most populous borough, Brooklyn, is home to nearly 2.6 million residents. If Brooklyn were an independent city it would be the fourth largest city in the United States. While Brooklyn has become the epitome of ‘cool and hip’ in recent years, for those that were born here, raised families here and improved communities over the years, Brooklyn has never been ‘uncool’.