Yearly one-night homeless count draws criticism, defenders

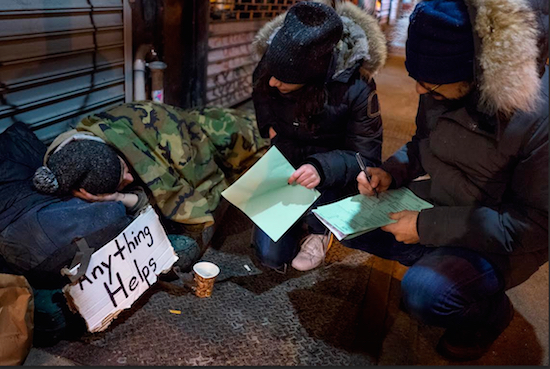

Over the past few weeks, thousands of clipboard-toting volunteers have fanned out across some of the nation’s largest cities, tasked with a deceptively complex job: counting the number of homeless people sleeping on the streets.

And under federal rules, they’ve had to do it under difficult conditions that some social service groups say are bound to produce an inaccurate tally. The official counts are done only once a year, in the dead of winter, when homeless people are more likely to be hunkered down in places that are hard to see.

The count is mandated by the federal government in order for the cities to receive certain kinds of funding. It has taken place all over the country in the last few weeks in cities such as Philadelphia; Houston; and Boise, Idaho. But it has faced significant criticism.

Brooklyn Boro

View MoreNew York City’s most populous borough, Brooklyn, is home to nearly 2.6 million residents. If Brooklyn were an independent city it would be the fourth largest city in the United States. While Brooklyn has become the epitome of ‘cool and hip’ in recent years, for those that were born here, raised families here and improved communities over the years, Brooklyn has never been ‘uncool’.