Capote’s ‘Brooklyn’ memoir brings to life Brooklyn Heights in the mid-20th Century

“Brooklyn: A Personal Memoir with The Lost Photographs of David Attie” by Truman Capote, published in 2015 by The Little Bookroom, N.Y., with an introduction by George Plimpton and afterword by Eli Attie

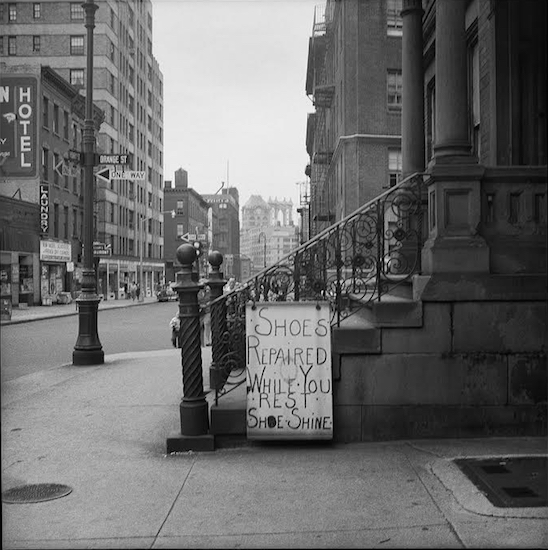

It was only a little more than a half-century ago. Brooklyn Heights in the late 1950s — 1958, to be exact. Truman Capote had just published “Breakfast at Tiffany’s.” He had been living in the Heights for a while when he had a meeting with an editor of Holiday magazine. They were interested in publishing something of his. We don’t know for sure, but he might have asked, half-jokingly, “How about an illustrated piece about Brooklyn?”

The idea was a fresh one, especially for Holiday magazine. It was outré enough to tickle their interest and he was off and running. Capote knew just the photographer for the job, David Attie, with whom he had just collaborated on a Hearst magazine article.

Brooklyn Heights

View MoreRead the Brooklyn Height's Press and Cobble Hill News. Find out more about Brooklyn Height's History here.