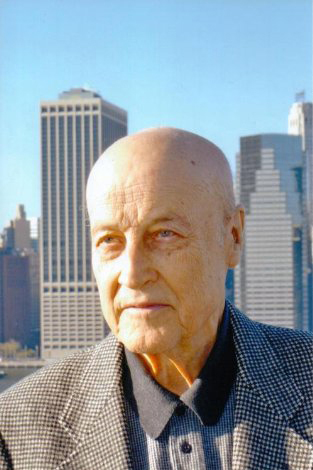

Henrik Krogius, Emmy-award winning editor of Brooklyn Heights Press, retires

Henrik Krogius – world traveler, Emmy-award winning news producer and editor of the Brooklyn Heights Press for 22 of Brooklyn’s most transformative years — has announced his retirement.

“My career has gone through many changes, from movie house newsreels to early-days black-and-white television, to color television and satellite transmissions, and back to the traditional weekly newspaper,” he writes in his farewell editorial (see below). “I’ve sometimes felt I was a living anachronism, watching obsolescence take over everything I was involved in. Perhaps it’s time for something more restful, or, in any case, some project not bound to the insistent wheel of progress, or ‘progress.’”

At the helm of the 75-year-old Brooklyn Heights Press and Cobble-Hill News weekly, Krogius chronicled his neighborhood’s change from a “insular, Manhattan-oriented world” to its present day as part of a transformed Brownstone and Downtown Brooklyn. His award-winning photography, insightful editorial comment and a deep working knowledge of Brooklyn’s history made the paper a must-read for residents of the Heights.