On This Day in History, January 18: He Dug Up the Dirt

“Good evening, Mr. and Mrs. North America and all the ships at sea, let’s go to press! — FLASH! NEW YORK!”

This opening was probably not yet used by Walter Winchell on his first radio program of political commentary and celebrity gossip on Jan. 18, 1929, but it was heard on most of his programs for the next 28 years.

Walter Winchell was born in New York City on April 7, 1897. Winchell matriculated on the stages of vaudeville; his education had ended in the sixth grade. By 1910 he was working at the Imperial Theater, where he, Jack Weiner and George Jessel formed a trio of singing ushers. Gus Edwards took them on as part of his “Newsboys’ Sextet,” an act Winchell worked for two years. He continued in vaudeville until 1917, when he joined the Navy. He returned to the stage when his hitch was up.

Winchell’s career as a reporter began in 1922. He worked for several newspapers as a drama critic, later becoming a gossip columnist for the New York Daily Mirror. His column “On Broadway” oftentimes carried out personal vendettas against politicians and show business celebrities. Eventually the column was syndicated and appeared in newspapers in 50 states and 11 foreign countries.

By 1932, he started to benefit from what would be an 18-year sponsorship by Jergens Lotion, and he had become the most important and powerful reporter in the nation. His radio show was often in the top 10. This, coupled with his syndicated newspaper column, gave him an unprecedented influence in national affairs.

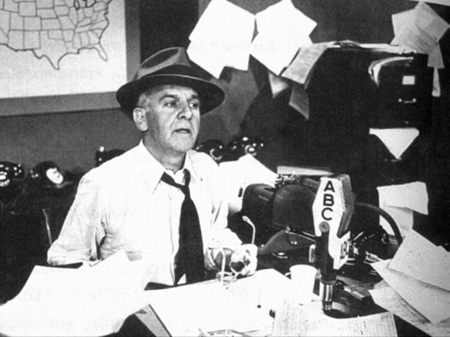

Winchell made his name as a reporter but he was first of all a showman. His newscast was an act: he was an entertainer, too sloppy and careless to be taken seriously by so-called serious journalists, but far too powerful to ignore. In the same breath he could report the doings of nations and the most piddling snatches of Hollywood pillow talk. This he did in a stream of invective, clocked at 215-words-per-minute and underscored by the chattering keys of a telegraph “bug,” which he himself manipulated. He sat at the microphone in the classic pose of the day, the hard-bitten reporter wearing a fedora hat, his script held out in his left hand while, with his right, he jiggled the telegraph key and made his opening speech to “Mr. and Mrs. North America.”

Winchell’s tireless pursuit of New York gossip became legendary. With the permission of the police, he sped through New York’s streets in a car equipped with a radio receiver, a flashing red light and a siren (sometimes beating police and firefighters to the scene). Although he disliked celebrities, he kept a table at the fashionable Stork Club, where he held court in the evening and dug up the latest dirt on starlets, G-men, and what he called “debutramps.”

But if the gossip was hot, it was the columnist’s way with words, known as Winchellese, that was his true trademark. His pithy remarks were salted with terms of his own invention.

During the 1930s and 1940s, Winchell’s renown was such that a favorable mention in one of his columns could make a book a best-seller or turn a movie into a box-office hit. His prominence also brought him into contact with the underworld: gangsters wooed him, mobs provided him with free bodyguards, and one hit man actually used Winchell as his intermediary when surrendering to the FBI.

As the years passed, however, Winchell’s political commentary grew ever more strident. An ardent anti-Communist and champion of the McCarthy investigations, he devoted more and more of this column space to feuds and vendettas. Broadway, meanwhile, was losing its glitter, and by the 1960s Winchell’s star had faded. As one observer noted, “You can’t be the historian of something that no longer exists.”

After his retirement from radio, Winchell was active in television. He narrated the ABC gangster melodrama The Untouchables (1959-63). Winchell’s memoirs were published as Winchell Exclusive in 1975. He died in Los Angeles, on Feb. 20, 1972.

Leave a Comment

Leave a Comment