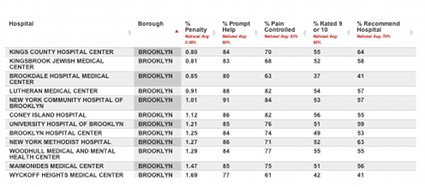

Brooklyn hospitals to be hard hit by new penalties

Brooklyn%20hospitals%20chart.jpg

Beginning this week, hospitals across the country are getting judged by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services on how well they serve their patients – and in New York City, the result could be millions of dollars in lost federal funding.

Under the new “pay for performance” rules of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, hospitals that uphold high standards of care and have well-treated, satisfied patients will see financial rewards.

Those that fall short will be penalized up to 2 percent of their Medicare reimbursements for each patient they treat under the federal health insurance program for the elderly and disabled.